Within the project “Creators” T-invariant together with RASA (Russian-American Science Association) continues to publish a series of biographical essays about people from Russian Empire, who made a significant contribution to world science and technology. The essay is dedicated to astronomer Alexander Vysotsky. He was born in Moscow, but most of his life he had worked at the observatory of the University of Virginia. There he compiled the first catalogue of red dwarfs and experimentally confirmed the rotation of our Galaxy.

Heavy accent

Professor Alexander Vysotsky spoke English with a strong accent until the end of his long life. However, among American astronomers, this was not such a rare occurrence. Nikolai Bobrovnikov, Georgy Gamov, Otto Struve — astronomers and astrophysicists, immigrants from the Russian Empire — worked in various American universities. Many of them could speak French and German from childhood, but not English. He had to study at a mature age. Vysotsky’s wife was an American. The son became a famous American mathematician. But Vysotsky was also accepted into the “Raven Society” — a closed club of scientists at the University of Virginia. True, prior to this, Vysotsky had worked at the university observatory for 30 years. Vysotsky left the university 65 years ago, but his strong accent still remains: the University of Virginia annually awards a scholarship in his name to the brightest astronomy students.

Astronomer Lieutenant Alexander Vysotsky

Alexander Nikolaevich Vysotsky was born in Moscow on May 23, 1888. We do not know anything about his parents and family. It is possible that he belonged to one of the five branches of the Vysotsky nobility. After graduating from the gymnasium, he entered the Faculty of Physics and Mathematics of Moscow University. There he was among the members of the Moscow Circle of Astronomy Lovers. At that time, astronomy was a prestigious hobby among intellectuals. Even the artists-brothers Apollinaris and Viktor Vasnetsov, who were also members of this circle, became interested in it.

The members of the circle had at their disposal several good telescopes at once (refractors with a diameter of 3 to 6 inches), donated by individuals. In December 1909, the circle members were the first in Moscow to photograph Halley’s comet. Participants reported on their observations at circle meetings and even published the results in scientific journals.

Vysotsky immediately established himself as an enthusiastic young scientist and educator: he made presentations on astronomy (on the structure of the universe), lectured in the Knowledge of the Sky circle for workers. Actively participated in the calculations of tables for the “Russian Astronomical Calendar” and the yearbook of the Russian Astronomical Society. Together with Professor Konstantin Baev, he compiled an Atlas of Astronomical Pictures, published in 1915.

In 1913, Vysotsky was enrolled in the Nikolaev Main Astronomical Observatory (now Pulkovo), where he worked under the guidance of the famous astrometrist Sergei Kostinsky. The young scientist immediately presented to the director of the observatory, academician Oskar Backlund, a ten-year plan for observing the movements of 700 binary stars. But Vysotsky only had a chance to work at the observatory for two years. The First World War began, and in the fall of 1915 he was drafted into the army.

Having a good command of several languages (including French and German), Vysotsky became an intelligence signalman. He was engaged in the interception and decoding of enemy radio messages. He successfully coped and received the rank of lieutenant. The radio station where he worked was only 10 km from the Pulkovo Observatory. This allowed him to keep in touch with colleagues. Hope to return to astronomical work after the war, he remained.

But after the Bolsheviks came to power, Vysotsky joined Denikin’s army, and together with its remnants emigrated to Constantinople.

From Constantinople to Virginia

From Constantinople, Vysotsky moved to Tunisia, where for some time he taught natural sciences to other refugees from the Russian Empire. However, luck smiled on him further. An article published in a German astronomical journal helped him secure a position at the University of Virginia in the US. However, connections also played an important role.

“Vysotsky got here thanks to Struve, — recalled his longtime colleague and co-author Piet van de Kamp. — Vysotsky, like many immigrants from Russia, fought the communists and was left with nothing. White lost, as we all know. These White Russians were taken care of for some time, given the opportunity to get an education, and Vysotsky led the translation lawsuit with Struve. And Struve is with Mitchell. Mitchell needed another man for the observatory. Mitchell asked Vysotsky to come, and he came”.

Well-known in scientific circles, Otto Struve himself managed to go through hardships and understood the difficulties of his colleagues. Struve’s name was well known — he belonged to an illustrious family of astronomers. His great-grandfather Vasily Struve was one of the founders of stellar astronomy. He stood at the origins of the very Pulkovo Observatory, which was actually built for him and according to his project. (Both grandfather, and father, and uncle Otto Struve were also famous astronomers. We plan to devote a separate essay to Otto Struve).

Otto Struve, like Vysotsky, fought in the White Army, and later ended up in Constantinople without work and clear prospects. But he maintained both business and close friendships with many former compatriots who found themselves in exile in the United States and with American astronomers. Thanks to his personal petitions, many young emigrants got jobs. Vysotsky also belonged to them. He began working at the University of Virginia in 1923.

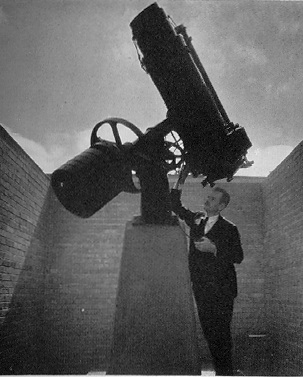

The scientist was doubly lucky: at the University of Virginia at the McCormick Observatory at that time was the largest telescope in the United States and the second largest telescope in the world. Beginning in 1914, the director of the observatory, Samuel Mitchell, led a program to measure the distances to nearby stars. Vysotsky and his wife Emma Williams-Vysotskaya also made a huge contribution to it. Emma was also an astronomer. She got her PhD from Harvard. They married in 1929. Emma became a true friend and co-author of Vysotsky for more than forty years.

Vysotsky’s cottage on the territory of the University of Virginia, next to the McCormick Observatory. The University of Virginia bought the building in the 1960s. A painting by Edward Thomas.

Red dwarfs and the rotation of the Galaxy

Alexander and Emma Vysotsky, together with colleagues, compiled a catalog of red dwarfs close to the Sun — dim and cold stars. A 10-inch refractor donated to the university by the Carnegie Institution of Washington was well suited for this analysis. An objective prism was installed on it, which made it possible to simultaneously record the spectra of all stars on one photos. The spectra allowed Vysotsky and his colleagues to classify stars according to surface temperature and gravity. They were able to identify tens of thousands of red dwarfs. This directory has not lost its significance so far.

In 1926-1927, the Swedish astronomer Bertil Lindblad and the Dutch astronomer Jan Hendrik Oort suggested that our entire galaxy rotates. But their study was only confirmed by observations of the movement of the brightest stars (mostly blue giants). And this is not enough.

Vysotsky and van de Kamp noticed in the 1930s that the photographic motion of stars depends on their spectral type. The photographic proper motion of stars is determined by their displacement relative to a group of reference stars in photographs taken at different times. But the method gave many systematic errors, which arose due to the difference in the brightness and color of the stars, their position on the plate. These conditions are difficult to calibrate because they are affected by changing observing conditions (including atmospheric transparency).

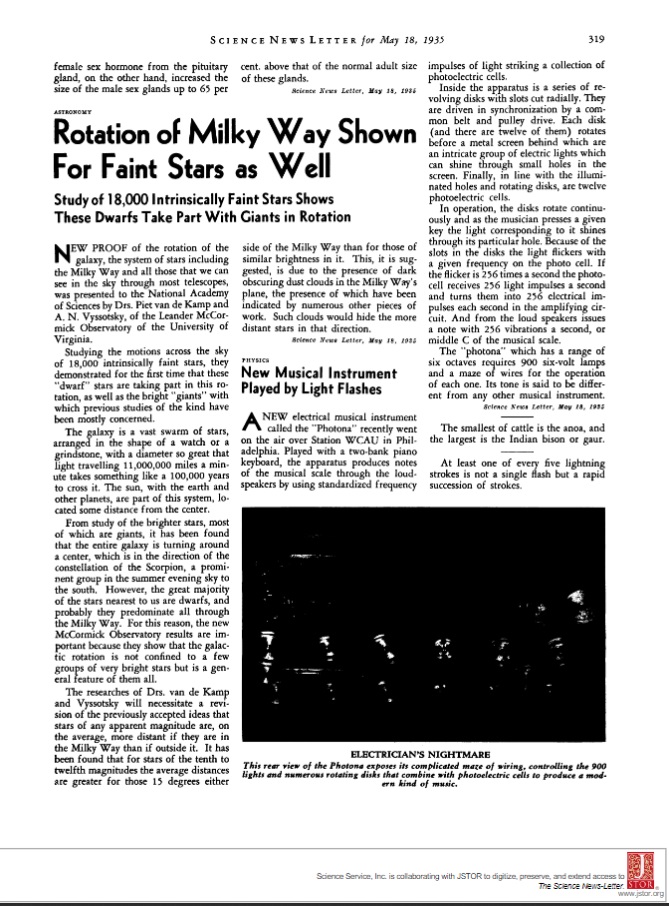

Science News Letter page, May 18, 1935, summarizing the paper by Vysotsky and van de Kamp on the rotation of the Galaxy.

Vysotsky and van de Kamp estimated the group velocity dispersion of red dwarfs. This made it possible to calibrate the photographic movement. As a result, astronomers have confirmed the rotation of our Galaxy, but not on individual bright stars, but on tens of thousands of red dwarfs. Astronomers have almost exactly calculated the duration of the galactic year, that is, the time it takes for the Sun to complete one revolution around the center of the Galaxy, about 200 million years.

“Like a crow…”

Vysotsky worked at the McCormick Observatory for 35 years before retiring in 1958. He did not lose touch with his homeland and from time to time sent articles for the Russian Astronomical Calendar, published by the Nizhny Novgorod Circle of Physics and Astronomy Lovers. In this edition in Three of his articles were published between 1927 and 1934. He carried on extensive correspondence with his Soviet colleagues and followed their work. Since the early 1950s, Vysotsky, in collaboration with the Harvard College Observatory, has been abstracting articles from Soviet astronomical journals. He also wrote abstracts for Russian papers presented at American and international conferences.

Vysotsky was respected at the university not only for his scientific merits. He played the violin in the observatory’s orchestra. The orchestra was led by Piet van de Kamp, and Vysotsky was the first violin in it.

In 1953, he was elected a member of the Raven Society, named after one of the university’s most famous alumni, Edgar Allan Poe. “Like an omnivorous crow that roams in search of food, the members of society must engage in a relentless search for knowledge”, wrote Professor of English Literature Charles Kent.

After Vysotsky left, his place was empty for a long time. Many of the programs he started had no one to continue, and they were curtailed. Alexander Vysotsky died on December 31, 1973 at the age of 85. Shortly thereafter, the University of Virginia established the Vysotsky Scholarship, which is awarded to outstanding students for work in the field of astronomy.

About a son

The fate of the Vysotsky’s son, Viktor, was also interesting. As a mathematician and computer scientist, he was one of the first creators of computer viruses. In 1961, while working at Bell Telephone Labs, Viktor Vysotsky invented a game with the eloquent name “Darwin”. Programs written in assembler (they were called “organisms”) during the game had to displace the “organisms” loaded by another programmer. The winner was the one whose “organisms” were able to harm others and disable them.

Later, the principles of operation and the source code of this game served as an inspiration for several creators of the first computer viruses. As, however, and anti-virus programs. Many ideas of the UNIX operating system are associated with the work of Viktor Vysotsky.

Sources:

Vysotsky family tree

Biography of Alexander Vysotsky on the website of the University of Virginia (archived copy)

The Raven Society website (The Raven Society)

Oral History Project. Niels Bohr Library. Conversation with Piet van de Kamp

The rotation of the Milky Way is shown for dim stars. Science News Letter, May 13, 1935

Illustrious Immigrants. The Intellectual Migration from Europe, 1930-41. Laura Fermi. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, 1968.

Balyshev M. Otto Ludwigovich Struve, 1897-1963. M., 2008.

Russian Abroad. Golden book of emigration. First third of the 20th century. M., 1997.

Encyclopedic biographical dictionary. M., 1997.

History of computer viruses. About Viktor Vysotsky.

Author of the essay Anton SOLDATOV

Project “Creators”. T-invariant in collaboration with RASA (Russian-American Science Association) supported by Richard Lounsbury Foundation

Man of the earth. Essay on the biography and scientific activity of Zelman Vaksman

Georgij Kistyakovsky, the unknown father of the American bomb

Anton Soldatov 6.09.2023