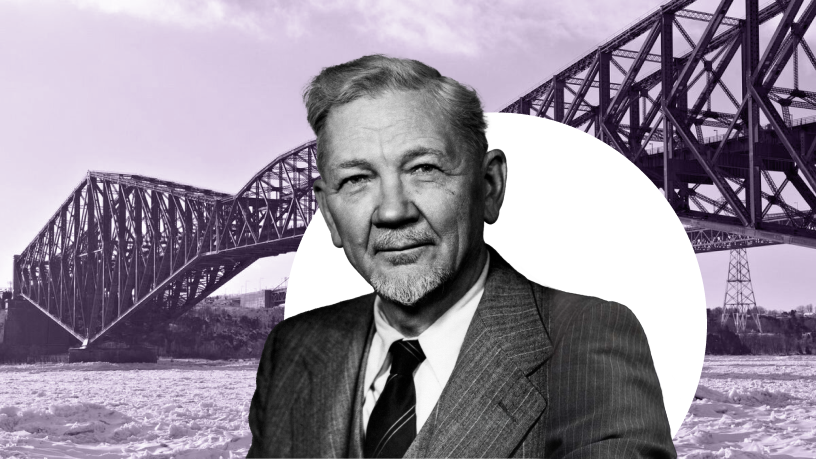

The eighth essay from the “Creators” series is dedicated to Stepan Timoshenko , an outstanding mechanical scientist, engineer, one of the creators of the theory of strength of materials. In the “Creators” project T-invariant together with RASA (Russian-American Science Association) continues to publish a series of biographical essays about people from the Russian Empire who made significant contributions to world science and technology, about those to whom we owe our new reality.

In the USA, Stepan Timoshenko, a native of Konotop district, is considered literally the father of applied mechanics. And in Russia and Ukraine, where the scientist wrote his most important works, few people know his last name. Meanwhile, Timoshenko managed to make an impressive scientific career both at home and in exile. And along the way, become a co-founder of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. This is a story about how a pre-revolutionary student could build an entire railway station. How professors fled to Istanbul in a dirty and wet ship hold. How emigrants from the Russian Empire changed the face of Yugoslav universities and American corporations. And also about a grumpy professor who never liked anything, and whom, despite this, everyone loved.

Stepan Prokofievich Timoshenko was born on December 22, 1878 in the village of Shpotovka, Konotop district, Chernigov province. The first 20 years of his life resemble a classic biography of the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. An old neglected garden that a boy explores during the summer holidays, Russian classical literature, teachers, classmates, earning money by private lessons, enrolling in St. Petersburg, revolutionary circles, student unrest.

All this took place, – with three, but very important differences. Firstly, his father, Prokofy Timoshenko was not a nobleman, but a land surveyor, who got wealthy. He bought the estate and kept the farm in exemplary order. The young man knew the peasants well and did not idealize them. He will later remember that he did not believe in the possibility of socialism in the countryside and therefore did not sympathize with the Socialist Revolutionaries (“Эсеры”).

The second aspect is linguistic. Timoshenko was Ukrainian; the family spoke Surzhik. His brothers later became figures in the Rada and the Ukrainian government in exile. Timoshenko himself was worried for a long time about what he thought was the “wrong” Ukrainian accent. And even after becoming one of the founders of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences, all his life he stubbornly considered himself Russian.

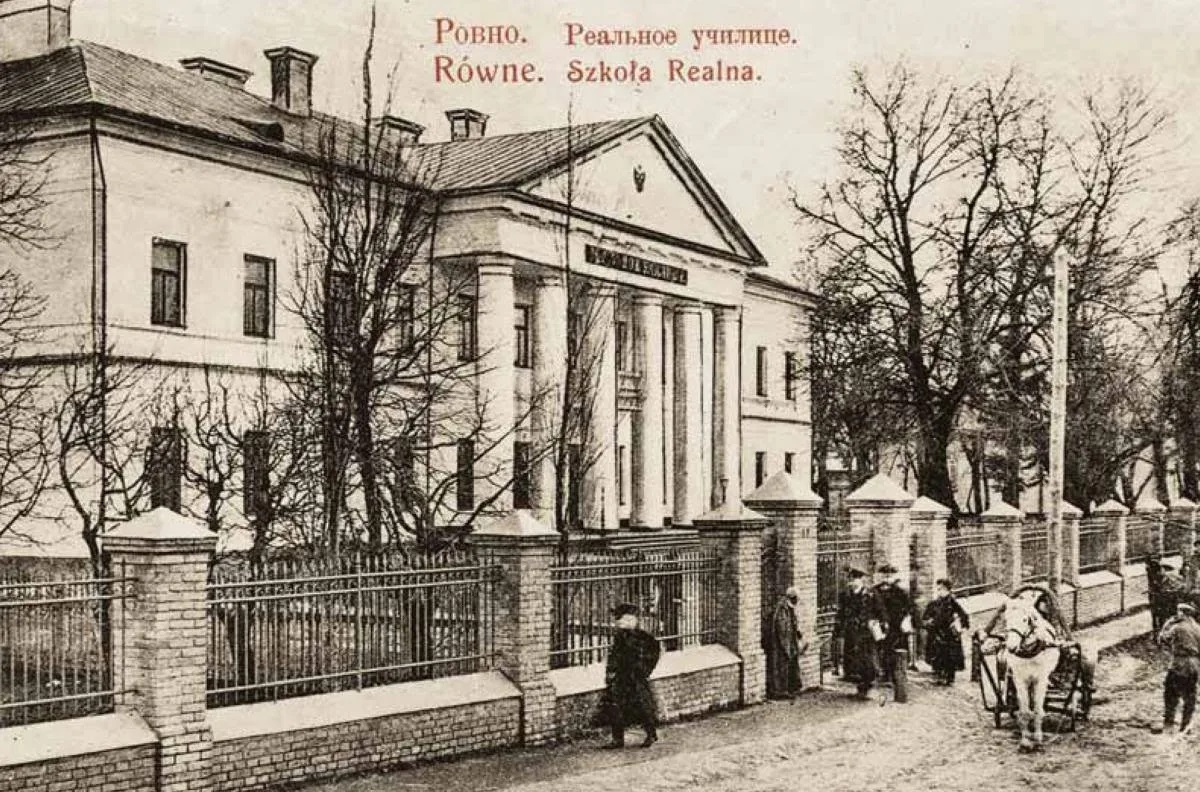

The third difference is the education received. Timoshenko did not graduate from a gymnasium, but from a real school. He didn’t study Latin, Greek, or English, but mastered engineering sciences. This later helped him a lot as an engineer, but he was really lacking in languages. And all his life he caught up with this gap, learning German and English for a long time and with a hard effort.

Rivne Real School. Source.

Stepan Timoshenko left behind a voluminous and rather unsophisticated autobiography, simply titled “Memoirs”. Of course, like any memoir, the book carries somewhat distorted optics. And the academician already describes his childhood through the eyes of a future engineer and teacher.

For example, we see that all sorts of technical devices fascinated him from an early age. Let’s say, in a pile of sand he built not only castles, like all other children, but also railways.

The strongest childhood impression was the steam thresher, which his father borrowed every year from a neighboring landowner. And for the entire three weeks that the machine was working, Styopa did not leave it one step.

Finally, the most vivid childhood engineering memory. His father bought a neighboring estate, where literally everything needed to be rebuilt. Stepan was already 14 years old, thanks to a real school, he knew how to draw and paint. And Prokofy Timoshenko invited his son to participate in the design and construction.

Stepan studied all the drawings of houses and all the new buildings that caught his eye. And even sometimes, during boring lessons, he drew future decorations and designed a porch. In the end, he even glued together a model of the house out of cardboard.

These are the memories of Timoshenko the engineer. And as a teacher, he describes for a long time and a little boringly the methods of all his teachers: from the young man who prepared him for entering the school, to the St. Petersburg professors.

How he himself did not like and considered long classroom lessons useless. How a tough and demanding mathematics teacher aroused interest in this science. As a future scientist himself, he discovered his love for teaching – helping his friends who were struggling with mathematics. For this reason, he even came to school early, before classes started.

In the whole country, railway engineers were trained at that time in one single place – at the Institute of Railway Engineers in St. Petersburg. The competition was 5 people per place, but Timoshenko successfully entered.

Pre-revolutionary higher education was very different from all modern practices, both Russian and Western. Strict attendance was not required from the student, and teachers did not have a curriculum or set program over them. So the human factor played a huge role.

Let’s say a future academician, having become familiar with the professors’ teaching style, decided to listen to lectures only on mechanics and chemistry, and learn all other subjects from books. Even then, he noted that all courses lacked “rationally organized practical exercises.”

What did the students who ignored the lectures do? The first half of the day, before the drawing rooms opened, they sat in the buffet and read newspapers. The cafeteria was not a university structure, but an element of student government. And the revenues from the sandwiches went towards building a library, which wasn’t devoted to engineering at all: there was a lot of fiction, books on sociology and economics, a lot of Marxist literature.

Timoshenko himself admitted that he tried to read Capital, but “I never had enough energy or time to completely overcome this voluminous work.” He had leftist views, like most students, but was not a member of political organizations. The Narodniks (“народники”) did not suit him because he knew the peasants well. And Timoshenko was turned away from their main competitors, the Marxists, by appeals to workers, which incited hatred of enterprise owners and the bourgeoisie. Almost 70 years later, the aging professor, writing his memoirs, sincerely tries to understand the reasons for the total passion for the leftist ideas of his classmates. He will remember how back in school no one liked compulsory church attendance and military gymnastics. That the cadets were always lazy realists who had no hope for a university education, and all this caused some hostility among the officers. And direct acquaintance with how poor and unfair the life of the peasants was, aroused a general desire for social justice.

“I was interested in the struggle for democratic principles, for political freedoms, and the introduction of socialism seemed to me a matter of the distant future. For now, I considered it necessary to support the interests of the weak, as far as possible within the framework of the existing system,” the scientist concluded. And apparently many young people of that generation thought something like this.

A very important part of engineering education in pre-revolutionary Russia was summer practice. The country was then quickly covered by a network of railways. But there were not enough competent railway workers. So a fourth-year student could well be tasked with designing an entire train station.

This is exactly how Timoshenko practiced in the summer of 1899 and summer of 1900. He participated in the construction of the Volchansk-Kupyanskaya railway in the Kharkiv region and designed, for example, the Kupyansky railway station. We know both of these toponyms well from the chronicles of Russia’s full-scale invasion of the territory of Ukraine. But then there was no war there, but just a rather poor and remote countryside.

Monachinovka station, which was built by Timoshenko

In two years, a dropout student laid a water supply system at one of the stations and erected station buildings. He designed the station and built locomotive depots. And half a century later, having already become an American professor, Timoshenko will regret that his students do not have such opportunities.

Scientist

In Russia at that time there was universal conscription. Timoshenko decided to honestly serve the allotted year and treated this time in advance as if it had been erased from his life. The main thing is to serve in St. Petersburg so as not to lose contact with the institute. So the young engineer ended up in the Life Guards Sapper Battalion.

Over time, he came to the conclusion that this year was also a useful experience. “First of all, here I spent a year with people my age, mostly from villages, in conditions of equality. This is not at all like meeting the peasants of your village, being the son of a landowner,” he will recall.

Two things contributed to the closeness with his colleagues: Ukrainianness and love for teaching. As in any guards unit, the officers were mainly busy with their secular affairs, and the entire functioning of the battalion was carried out by the non-commissioned officers (унтеры).

The company sergeant major and several non-commissioned officers he selected were Ukrainians. But they, unlike St. Petersburg students of Ukrainian origin, have not yet been touched by a passion for national culture. Timoshenko recalls how he invited three non-commissioned officers to the play “Cossack beyond the Danube”.

“The performance, the Little Russian dances (malorussian dances), and the Little Russian (malorussian) conversation all around – all this made a stunning impression on my military friends,” the engineer later recalled. “They believed that the Little Russian (malorussian) language was the language of low men (“мужиков”). And then suddenly students and smart ladies speak this language and dance hopak, just like they do at home in the village. But they sing much better than in the village. There were so many conversations in the barracks after this performance!”

In addition, Timoshenko decided to prepare non-commissioned officers and the most competent soldiers to enter the school of foremen after service (школа десятников) – an educational institution that trained masters and foremen for construction sites.

And during his service, the engineer designed a bridge made of light poles and wire that could be carried by two soldiers. Timoshenko admits that this happened “out of nothing to do.” But the bridge was a great success and was even presented to the general.

After the army, the engineer first got a job in the laboratory of the Railway Institute, where he was involved in testing cement, and then testing rails. Then he became a laboratory assistant at the St. Petersburg Polytechnic. There he had to work with people – conduct practical classes with students in a mechanical laboratory.

By that time, Timoshenko had come to the firm conviction that mathematics should be taught to engineers in a completely different way than to mathematicians. What is important is to give practical applications of all knowledge. And even good mathematicians often don’t teach this.

With this approach, the young scientist began to compose problems, from which he compiled a problem book that later became famous and was translated into different languages. Half a century later, at Stanford, he would use the then St. Petersburg examples in his classes.

Russia was losing the war to Japan. The first revolution was inexorably approaching. Students were worried, universities stopped classes. And Timoshenko used the resulting pause to visit the University of Göttingen. His acquaintance with the German engineering school would make him a convinced Germanophile for a long time. He liked that machines for laboratories were not bought “in reserve”, as in Russia, but with a clear understanding of what they were needed for. I liked that the professors did not repeat the same lectures year after year, but supplemented them as science developed. I liked the openness and democracy in universities.

At the time of revolutionary events, Timoshenko published his first scientific work, “On the phenomena of resonance in shafts.” He also prepared a theoretical basis and experiments for a future dissertation on the lateral stability of an I-beam.

In 1906, while all universities were still closed due to the revolution, a young scientist took part in a competition to occupy the department of strength of materials at the Kyiv Polytechnic. And he won. Despite the fact that Timoshenko was only 28 years old and with all the experience of laboratory classes with students, he had never given them a single lecture.

Nevertheless, the success of the young professor in Kyiv was stunning. He owed this to a rather obvious, in modern view, innovation. The idea was that in parallel with the lecture course on strength of materials there would be classes in the laboratory. And students could immediately test all new formulas in action, using simplifying assumptions accepted in engineering practice. For some reason, no one thought of this before Timoshenko. There weren’t even suitable instruments in the laboratory; the scientist had to design them himself.

I also had to write a textbook. And by 1911, a book was published that was accepted in most Russian educational institutions. Decades later, Timoshenko will rework this course and publish it in English. Translations into other languages will appear.

In 1909, the young teacher was elected dean of the civil engineering department. Two years later, he and two other deans would be fired for political reasons because of Jewish students.

Anti-Semitism in the Russian Empire was established by law; in particular, there were quotas for the enrollment of Jews in universities. For the Kyiv Polytechnic the quota was 15%. After the revolution, the institute began to ignore this restriction and enrolled many more Jewish students. Now the ministry insisted on their expulsion. Timoshenko, who treated Jews with some prejudice, nevertheless refused to expel them. All this ended with the dismissal of him and two other equally stubborn deans and the immediate resignation of 40% of the professorship in protest.

Such dismissal meant loss of rights. State universities and state enterprises could no longer hire Timoshenko. But the scientist just published a textbook. In addition, he received his first prize – named after Zhuravsky, which came with 2.5 thousand gold rubles. And as additional sources of money, the disgraced dean taught hourly classes at institutes and acted as a consultant in the construction of dreadnoughts.

Around the same time, a fateful acquaintance took place. Timoshenko taught hourly classes in St. Petersburg. He lived on Aptekarsky Island and became friends with the Austrian physicist Paul Ehrenfest. He told his new friend about the latest trends in physics: quantum theory, the theory of relativity. They met in the mornings in the botanical garden, talked and drew the necessary drawings with a stick in the snow.

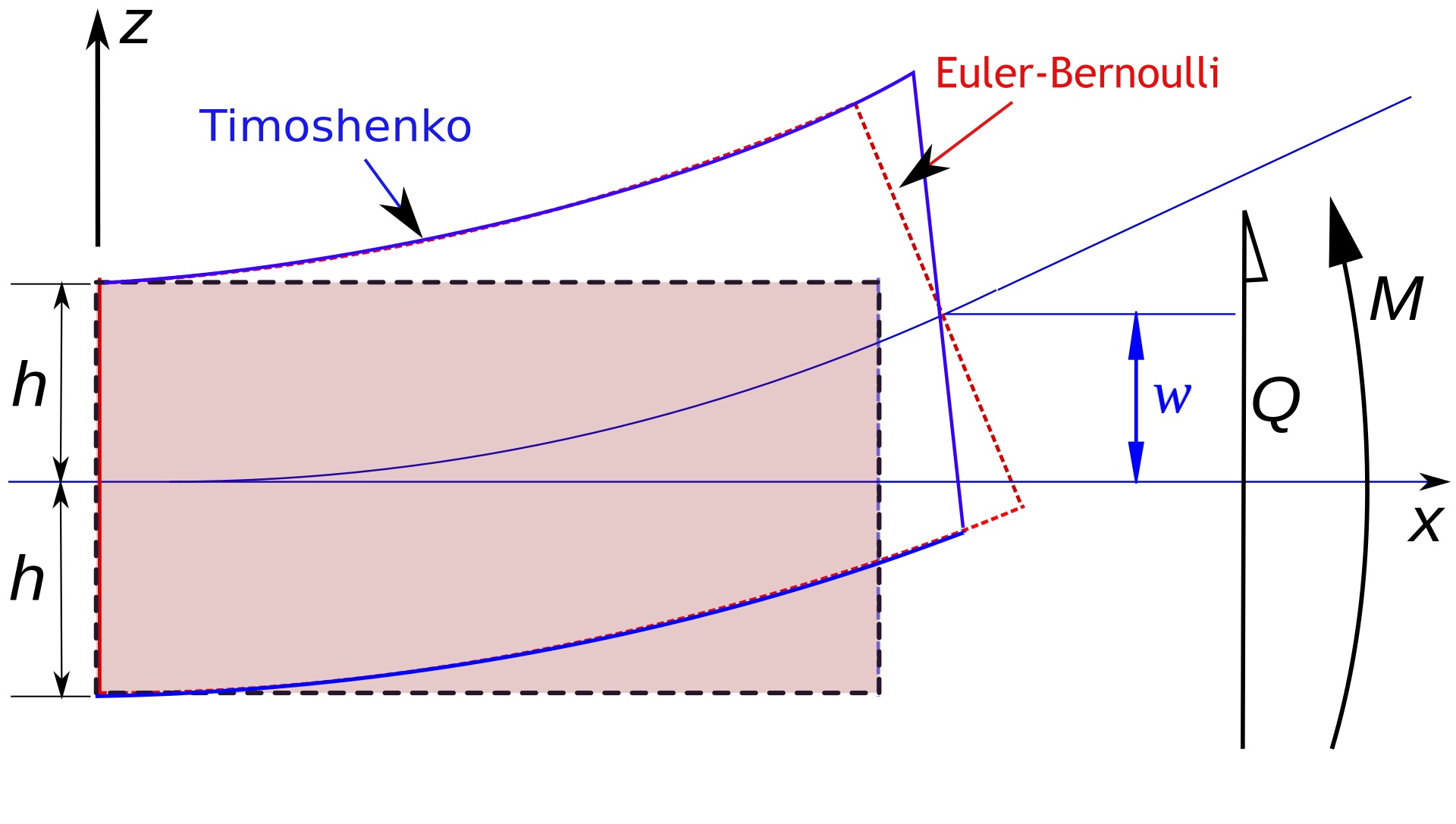

Soon the Austrian despaired of getting a professorship in St. Petersburg and left. And then the names of the two scientists were forever united in the history of science – in the theory of bending (Timoshenko-Ehrenfest beam theory) Timoshenko-Ehrenfest beams. It describes the behavior of beams taking into account shear deformation and rotation of cross sections.

Often the second co-author is forgotten and the model is simply called “Timoshenko’s theory,” and not only in the post-Soviet space. An entire scientific investigation is devoted to proving Ehrenfest’s role and trying to understand why his name disappeared .

Изгиб балки по Тимошенко-Эренфесту”>Beam bending according to Timoshenko-Ehrenfest

In January 1913, the disgrace ended. Timoshenko became a professor at the Puteya and Electrotechnical Institutes in St. Petersburg. The war has begun. Mobilization revealed many problems, including technical ones. And the engineer was involved in solving one of them – amplifying the strength of railway tracks in directions that were previously considered secondary, but now could not withstand heavy military trains.

Nevertheless, as during the years of the first revolution, Timoshenko did not take major political events to heart. While mass murder on the fronts of the First World War was forever changing the familiar world, the professor gave lectures and took exams, vacationed in Crimea and Finland. In his memoirs, he describes at length and in great detail all his vacations and walking routes.

Even during the war, Timoshenko wrote a book on the deformations of rods and plates, which was to form the second volume of the course on the theory of elasticity.

A revolution was approaching, which was no longer possible to ignore.

Academician

1919, Novorossiysk, the rear of the Volunteer Army, which had already begun to retreat, rain. Two academicians: Vladimir Vernadsky and Stepan Timoshenko – on the station square occupied by refugees. The happiest ones have tents, most just get wet. Academicians are in an intermediate position – they do not have tents, but they have umbrellas. Having opened them and stacked their suitcases under a tree, the scientists ponder their desperate situation.

Suddenly a young man appears and calls Timoshenko by name. It turns out that this is his former listener. He calls professors to some apartment where he lives with a group of young people who accompanied some train with military equipment and were stuck in Novorossiysk. They live in a commune, everyone chips in, shops at the market, and the landlady cooks for them. Timoshenko and Vernadsky are accepted into the commune, and so they live for three days, waiting for the right ship.

From many such chance meetings with people who remembered him and loved him as a teacher, Timoshenko’s odyssey during the Civil War and immediately after it took shape.

The revolution found him in the capital. “Having walked the streets of St. Petersburg in the first days of the revolution, I forever lost interest and trust in the colorful descriptions of the heroic performances of the insurgent people,” Timoshenko recalled.

In the summer of 1917, he sent his family early to vacation in the Crimea, and then decided to transport them to Kyiv to his father. Not for ideological reasons, but for purely everyday reasons: it was clear that the winter in St. Petersburg would be difficult, but the food supply in Ukraine was better. Timoshenko himself left at the end of 1917, barely squeezing into a carriage filled with deserters returning with rifles to their villages to divide the landowners’ land.

Timoshenko knew many of the ministers chosen by the Ukrainian Rada personally, as friends of his two brothers. They, unlike the scientist, were very interested in both politics and the national Ukrainian revival, communicated a lot with the local intelligentsia and after the revolution found themselves in the thick of public life.

Timoshenko himself was brought into this life against his will. It just became clear that it was impossible to return to St. Petersburg now. But the Kiev Polytechnic Institute, immediately after the revolution, offered to return to all teachers fired in 1911. And Timoshenko again took the chair of strength of materials.

And then, by chance, he also turned out to be one of the founders of the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences. Formally speaking, he fit all the criteria perfectly: a great scientist, a Ukrainian, a man who managed to work as a dean in Kyiv. But in practice, problems arose, since Timoshenko stubbornly denied his own Ukrainian identity.

Having been invited to the relevant commission, the scientist immediately told the Chairman of the Council of Ministers, Nikolai Vasilenko, that he was “an opponent of an independent Ukraine and even an opponent of the introduction of the Ukrainian language in rural schools.” Vasilenko diplomatically replied that in the field of mechanics this is not so paramount.

Despite his skepticism about Ukrainian independence, Timoshenko plunged into the process of creating the academy with interest. On this basis, they then became close friends with Vladimir Vernadsky. Timoshenko will continue to write to him even from exile.

The former rector of Kharkiv University, a geologist, worked with them on the creation of the academy Pavel Tutkovsky and historian Dmitry Bagaley. A little later, the orientalist Ahatanhel Krymsky, the economist and prominent Marxist Mikhail Tugan-Baranovsky, and the historian Fyodor Tarnavsky joined. In November 1918, the academy was created, and the members of the commission became the first academicians. Timoshenko headed the Institute of Technical Mechanics, which now bears his name.

The Hetmanate fell, the power of the Directory was established. But Timoshenko did not feel the political moment so much that he stubbornly refused to switch to the Ukrainian language. A member of the government summoned him, reprimanded him and threatened to fire the scientist from the Academy he created. Timoshenko writes: “I don’t remember what I answered to the member of the Directory, but I know that at the Academy I continued to speak Russian and did it not out of stubbornness, but because I did not know the literary Ukrainian language.”

The power of the Directory turned out to be short-lived and in general the year 1919 was remembered for the repeated transfer of Kyiv from hand to hand. Apart from minor episodes when the city was briefly occupied by different forces, from the beginning of February to the end of August the Reds ruled in it, and then the Volunteer Army took control.

In this whirlpool of events, Timoshenko either bowed to the Bolshevik minister to receive a budget for the academy, or hid in the village so that the departing Reds would not take him, a reserve ensign (прапорщика запаса), into their army by force.

The power of “White army” (“власть белых”) was much more pleasant and understandable to the scientist. And his old acquaintances were in charge of science. But if the Reds were ready to recognize Ukrainian institutions, the fighters for a “united and indivisible Russia” from the Volunteer Army were not.

Several months passed in fruitless attempts to strengthen the position of the academy. And then the Reds approached Kyiv again.

“In the event of the occupation of Kyiv by the Bolsheviks, my position as a reserve ensign who had evaded the Bolshevik conscription would become very dangerous,” the scientist reasoned, and alone, without his family, he went to Rostov-on-Don to look for work under the government of the Volunteer Army. Then he still believed in the victory of the “White army”.

But power crumbled, and with it the established mechanisms of life. And this became noticeable already on the road. So, at one station the train stopped, the passengers were told that they had run out of fuel and were sent to break down fences and drag them to the locomotive. Then the driver, conductors and conductors imposed a tribute on the passengers and declared that until they collected a certain amount for them, the train would not go further.

In Rostov, Timoshenko met an acquaintance from St. Petersburg and quickly joined the Military Engineering Council under the government of Southern Russia. I received a military uniform, identification cards and canned food from the warehouse. In general, he somehow strengthened his position, but not for long.

The volunteer army retreated under the attacks of the Bolsheviks. I had to leave Rostov and retreat to Ekaterinodar. Along with the army, the intelligentsia also left: scientists, teachers. And among them are Timoshenko and Vernadsky.

A general meeting of professors was organized to decide what to do next: wait for the Bolsheviks or leave? Timoshenko firmly chose the second. Moreover, Yugoslavia announced its readiness to accept refugees from Russia. Together with the mechanical scientist Georgiy Pio-Ulsky, Timoshenko even went to an audience at the Serbian embassy.

“I’m really thinking about leaving. It was very difficult under the Bolsheviks. I want to go into a big space: for 2 years you don’t know what’s going on in the West and in world literature. Timosh[enko] feels this very much,” Vernadsky wrote in his diary in those days.

And then the same trip to Novorossiysk awaited the two academic friends. A downpour, waiting for a ship, a random fellow traveler and life in a strange commune.

The ship arrived four days later, the academicians reached Yalta, where Vernadsky decided to spend the winter at his dacha in the hope that the affairs of the “White army” would improve. And Timoshenko went to Sevastopol, trying to get on an evacuation flight to Constantinople.

But this was not easy to do. The city was then occupied by interventionists from France. And French officials decided who to let on the ships. Timoshenko almost fell into despair, but chance helped.

“Once upon a time, even before the war, the Society of French Engineers awarded me an honorable mention for my work on structural mechanics and issued me a corresponding certificate signed by the minister. I kept this ID and presented it to the consul. The effect was unexpected. The consul changed his tone and issued permission for a place on the ship not only to me, but also to my companions and their families. This was, it seems, the only case in my life when a document on academic excellence was of practical use,” the scientist recalled.

And then a small cargo ship, hastily converted to carry passengers, went to Constantinople for three whole weeks. Another Ukrainian academician Taranovsky and his family and an engineer and former student, Yakov Khlytchiev, sailed with Timoshenko. Everyone huddled as best they could. Khlytchiev’s wife was given a place in the cabin, and he himself got a hammock in the hold. When it got colder, steam began to condense under the ceiling, real rain poured from there, and the engineer had to cover himself with an umbrella. Taranovsky and his family sat on some boxes. And Timoshenko built himself a bed from two logs and a board.

Emigrants get off the ship that arrived in Istanbul. 1921

Emigrant

In Constantinople, the refugees were quarantined on Halki, one of the Princes’ Islands in the Sea of Marmara. Life began from scratch. Each was given a bowl and a mug and assigned to houses, spacious but without furniture. We had to sleep on bags of straw and stand in long lines for free porridge. But in line it was possible to exchange a few words with some professor or colonel.

The quarantine is over. Taranovsky sold his gymnasium and university gold medals to buy tickets; the academicians boarded a third-class carriage and went to Belgrade.

And again, Timoshenko met students or readers of his textbooks everywhere, who helped them cope with the difficulties of emigration. In Belgrade, such an unexpected admirer turned out to be Professor Arnovlevich, who even before the revolution bought Timoshenko’s textbook and was preparing his lectures based on it. He invited the emigrant to stay at his sister’s house.

The same story repeated itself near Zagreb, where the scientist rented a room. As soon as the owner’s son heard his last name, he told how, in Russian captivity, he taught the strength of materials from his book. The owners immediately moved Timoshenko to better rooms.

At the University of Zagreb, the rector, as it turned out, had long known about the scientific work of the Russian engineer. And when it turned out that their author was sitting in front of him, the emigrant was immediately asked to take the chair of strength of materials. With the start of the semester, classes could begin.

Between his arrival in Yugoslavia and the start of teaching, Timoshenko did two important things. He wrote a paper on strengthening the edges of holes in metal sheets and traveled to Kyiv to pick up his wife and children.

This happened in April 1920, when newspapers wrote that Polish troops approached Kyiv. He immediately went to Warsaw, obtained a visa and left for war-torn Ukraine.

“In Kyiv, at the station, it was completely empty. There were no cab drivers, and I walked onto Gogolevskaya Street with my light luggage. The house was just starting to get up. My arrival was a complete surprise – during the seven months of my absence there was no news of me. Of the Kiev residents who left for Rostov and Crimea seven months ago, I was the first to return home,” the scientist recalled.

The academy helped the family survive the winter. The Polytechnic Institute paid his wife his salary and helped him with food. But the academicians themselves were in a rather pitiful state. Timoshenko attended one meeting and was amazed by the shoes of one of the famous mathematicians: the sole of the boot came off completely, and he tied it up with strings. “The costumes of many academicians had fallen into complete disrepair, and I, in the jacket given to me by the British in Rostov, seemed finely dressed,” Timoshenko wrote about this.

The relatives did not want to leave. Everyone again thought that life would get better under the Poles. But the scientist was persistent and turned out to be right. The Kyiv Poles themselves had already evacuated with all their might. They didn’t want to take locals on the evacuation train. And here again an accidental meeting helped.

“The evacuation was ordered by an engineer who was my student many years ago. He recognized me, opened one of the freight cars and let us all in. The train started moving. It turned out later that this was the last train to break through from Kyiv, our last opportunity to leave Russia,” Timoshenko recalled. “But we didn’t travel long and stopped again, not reaching the Bucha station, where we spent the summer in 1907. Here everything was familiar to us, but the view was unusual: on the left the village familiar to us was burning, on the right the retreating Polish troops were walking along the high road.”

The path was difficult. The academician and his family slept on straw among some agricultural machines. The train stopped many times. And once, for example, passengers had to line up in a chain and fill the locomotive with buckets of water from a well – the water pump was destroyed.

Nevertheless, Timoshenko, his wife and children arrived successfully, and a rather forgotten peaceful life began to flow in Zagreb. The children went to school, the father gave lectures. He mastered the Croatian language from newspapers – knowledge of Russian and Church Slavonic helped here. Of course, a lot of Russian words still popped up in the lectures, but the audience quickly got used to it.

For the first time after the war, Timoshenko went on a scientific trip. He visited Germany, France and England, where he met the young Soviet physicist Pyotr Kapitsa.

Two years later, the scientist unexpectedly received a letter from America from a former student at the St. Petersburg Polytechnic. He worked for a company that eliminated vibrations in cars. And he offered his professor a move and a salary of $75 a week.

The question was not easy. On the one hand, Timoshenko liked teaching, he liked the climate in Zagreb, the professors and the students. And he understood perfectly well that he would have to give up all this. But the professor’s salary was only enough for the bare necessities. He could not buy himself any clothes or furniture, not to mention his own home. There were also ambitions of a different kind; I wanted to translate and publish my books in European languages.

In general, the scientist tried to sit on two chairs. The semester was just ending, and he agreed that his place at the university would be kept until the fall. Timoshenko decided to work in America for three months and then decide what to do next.

Industrial engineer

The scientist immediately did not like the United States, and in almost all respects. Judging by letters and memoirs, Timoshenko did not like scientists, engineers and workers, libraries and universities, living standards and leisure, Americans and Jewish emigrants.

He didn’t like the lack of the usual distance between physical and mental labor. He wrote with indignation that a hammerer at a factory can earn more than an engineer, that a university professor himself carries heavy pieces of iron for experiments, and does not entrust this to a special person. That professors and engineers work part-time instead of doing science, that students fight.

There was only one thing that made him happy, about which he soon wrote to Academician Vernadsky: “There is no narrow “nationalism” that you encounter everywhere in Europe and which was especially unpleasant for me in small Slavic countries like Yugoslavia or Czechoslovakia.”

But Timoshenko was extremely irritated by American engineering structures. A separate angry passage is dedicated to the New York Overground Subway in his memoirs: “Their appearance was ugly. The designs were striking in their technical ignorance and were, in my opinion, dangerous for traffic. When trains passed and especially when they were braking at stations, the swaying of these structures reached completely unacceptable limits. I had already gotten some idea of the illiteracy of American engineers while studying the failed bridge in Quebec. But I still didn’t imagine that the New York elevated railway was built so poorly/incompetently.”

The criticism is harsh, but the scientist definitely had the right to it. It is he who will eventually create a full-fledged engineering school in the United States.

The company where Timoshenko was invited to work was located in Philadelphia. It turned out to be tiny – only five rooms. It was working on new engines for the navy, and the engineer began calculating crankshafts.

“Here no one was interested in engineering science and he would have to live in complete scientific loneliness,” he would later recall his doubts in those first American months. “I definitely didn’t like America. Staying in Zagreb, I was closer to scientific centers. I could sometimes participate in scientific congresses. He could publish his works in the best European publications. But, turning to the material side of the matter, the picture presented itself differently. In Yugoslavia I lived in complete poverty.”

This settled the matter. Timoshenko wrote two letters to Zagreb. One thing to the university that will not return. And secondly, for the wife to take her youngest daughter and come. The eldest daughter and son remained in Europe and entered the Berlin Polytechnic Institute. The scientist was determined to give them a good engineering education, and was absolutely sure that there was none in the USA.

Despite this, he missed teaching more and more and dreamed of getting a job at one of the American universities, which he also wrote to Vernadsky about. As soon as his company began to have financial problems in 1923, Timoshenko’s first act was to write letters to several universities. But they didn’t even dignify him with an answer.

But one of the largest industrial companies, Westinghouse, responded. She was preparing to expand the research department, which already employed several Russian immigrants who gave Timoshenko the most flattering characteristics.

And now a new place of work in Pittsburgh. This time, Timoshenko could see how a large American company works from the inside. What struck him most was that the engineers were sitting in what we would now call an “open office.” “Americans do not understand at all that mental work requires silence and some comfort,” he stated.

But at Westinghouse there were many emigrants like him. Timoshenko mostly communicated with them, organizing walks during his lunch break. The mood was so-so. Russian engineers did not really understand the electrical machines in which the company specialized, they experienced impostor syndrome about this and were afraid that they would be fired. But practice has shown that fundamental engineering training allowed each of them to make a good career in the USA.

A workshop at the Westinghouse plant in Pittsburgh. 1920s

Timoshenko’s close friend was the inventor of the kinescope and one of the fathers of television, Vladimir Zworykin. A fellow immigrant, he worked for Westinghouse and was a doctoral student at the University of Pittsburgh. Zworykin often drove his new friend to and from the plant in his car.

Timoshenko immediately showed that he was a valuable acquisition for the company. Invented and improved several small measuring instruments. Solved a number of complex engineering problems. And soon he began consulting for a variety of Westinghouse technical departments in the field of strength of materials. If something broke in a production car, and engineers needed to accurately determine the cause and prevent new breakdowns, they turned to him.

Here the scientist first drew attention to one of the significant advantages of engineering in the USA – scientific results achieved in the research departments of large corporations were much more quickly implemented in production. “This connection between science and technology, according to my observations, was being established more successfully in America than in Europe,” Timoshenko admitted.

Less than a year had passed in the new place when the emigrant had to try himself again as a lecturer. He was approached by a group of young engineers from the company who wanted to take a course in the theory of elasticity. There were 25 listeners. There was no time for this during the day. Therefore, Timoshenko taught them in the evenings, had a quick snack at home and returned to the factory. “So, probably for the first time in the United States, a course in the theory of elasticity was taught,” he notes.

Then these internal factory lectures turned into a permanent seminar. Not only Timoshenko himself, but also other engineers, had already read reports there, talking about different sections of mechanics.

At the beginning of 1924, the plant’s chief mechanical engineer, Eaton, decided to involve the new employee even more closely in training young colleagues. The company hired about 300 American engineering graduates every year. And for the first six months they studied, spending 2-3 weeks in different factory workshops. Then they were distributed according to production, but about one in five decided to continue their education within Westinghouse. They passed a special exam and could enter one of the internal schools: mechanics or electrical engineering.

In the first, Timoshenko was asked to read a course on strength of materials. He once again noted the poor theoretical training of American graduates. And he taught them a course that in Tsarist Russia was usually taken by second-year students.

Each theoretical section of the course was accompanied by the solution of applied problems in accordance with the approach outlined back in the Kiev period. These lectures later formed the first half of Timoshenko’s new American book, “Applied Elasticity.”

The company was interested in having the works of its researchers discussed at international scientific and engineering congresses. So Timoshenko ended up in Toronto in the summer of 1924 and spent several days on the university grounds. The atmosphere there was British, and the congress participants were mostly Europeans. And the scientist returned in great longing for university work.

The immigrant’s position at Westinghouse was secure. There was enough money not only for life, not only for children’s education in Germany, but even for parcels to relatives in the USSR. And Timoshenko wrote desperate letters to Vernadsky one after another. “The laboratories here cannot be compared with Russian ones, or even with Zagreb. The country is amazing! People live with material comfort and do without a newspaper, without a theater, without a decent bookstore, without libraries!! To get a decent scientific book, you need to write to Europe yourself,” he complained in correspondence.

The company was in many ways ready to meet Timoshenko halfway. In 1926 he was sent on a trip to universities and laboratories in Europe. He visited Great Britain, Germany, Switzerland and France, and took part in two scientific congresses over these few months.

In the USA, the scientist’s activities increasingly went beyond the boundaries of his native plant. He gave a talk at the University of Michigan. Gave a lecture for narrow specialists and professors at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. But the consulting work became less and less. Three graduates of the internal corporate school have already worked at the company’s plant – engineers who took Timoshenko’s course and solve most problems related to strength without outside help.

His original course on strength of materials was published in English, which greatly simplified the teaching. So the engineer even agreed with the director of the institute that he would be allowed to write a new book in a calm atmosphere in the afternoon – about vibrations in cars. Timoshenko explained to the boss that many of the company’s engineers’ difficulties were related to this topic, and enlisted his support.

The theoretical part of the new course was largely taken from Timoshenko’s Russian-language books. But the practical tasks were based on real examples from factory practice. In 1927 the course was ready.

In the spring of that year, the scientist received a telegram from the dean of the School of Engineering at the University of Michigan. A special department was established there for research work in mechanics. And Timoshenko was asked to take over. The dream was coming true.

The factory tried their best to keep him. They offered the official title of factory consultant and complete freedom from local regulations. They promised trips to any congresses in Europe and America. “It was all very tempting. But I knew that while I was at the plant, there would be no peace and I would not be able to work scientifically,” the scientist later recalled.

But they parted with the company on good terms. Timoshenko retained the position of visiting consultant. He had to visit the plant once a month and spend two days discussing mechanical issues with the plant engineers.

Founding Father

Needless to say, Timoshenko also immediately disliked a lot of things at the American university. He was surprised by the division of labor, in which all administrative work, including the invitation of new professors, is carried out by the university administration – people who often have no direct relation to science and teaching.

It was depressing that professors were required to sit in their offices from 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. And that engineering faculty typically use this time to complete outside assignments. But what irritated him most was the professor’s low social status.

He is accustomed to the European approach, where professor is a coveted and highly paid title. And in America in those years, good practitioners, be it a doctor or an engineer, were not at all eager to teach. Timoshenko soon became convinced that the engineers at the university were much less professional than their colleagues at the Westinghouse Research Institute. And envious, besides that.

“From the very first day of my classes at the university, I felt that the attitude towards me was not at all the same as at the factory. At the plant, engineers turned to me for advice and help. They were kind to me – I was not their competition. The situation was completely different at the university. Here I am a foreigner, speaking English poorly, placed in a privileged position,” Timoshenko recalled. Indeed, with his special department, he had to deal with students for very few hours. And he received twice as much money as ordinary professors.

Amazingly, even the students treated the teachers without any reverence. At some point, the scientist noticed that his boots were always dirty. He thought about it and realized that the university territory was dirty, and in some places wooden walkways were laid in the mud. And in these bottlenecks, students are not at all eager to give way to the professor. And Timoshenko himself, when meeting on the walkway, instinctively steps aside and gets his boots dirty. “I decided to change my behavior, not give way and go straight towards the student. Given my height and weight, this method turned out to be successful – the students gave way, and I began to come home with clean shoes,” he would later write in his memoirs.

At the same time, the students did not shine scientifically either. They entered universities with much less mathematical preparation than their European peers. And they approached their studies pragmatically. Derivation of the formula is not interesting if you can look into the reference book and immediately get a ready-made solution.

There was also a pragmatic attitude towards learning itself. Almost any career could be pursued without a degree. Therefore, no one particularly aspired to become a doctor of engineering sciences. Timoshenko decided to turn this situation around. And if students choose to go straight to the factory, then why not involve existing factory engineers in the expanded curriculum. Using his connections at Westinghouse, the scientist created a scheme in which some of the company’s young employees, after graduating from the internal factory school, could study for a doctorate at the University of Michigan under his supervision.

But since it was almost 500 km from Pittsburgh to Ann Arbor, where Timoshenko taught, it was eventually decided to transfer Westinghouse engineers to the University of Pittsburgh. Timoshenko no longer taught there, but helped develop rules for interaction between the university and the plant. What especially attracted doctoral students was that scientific work performed at a corporate research institute was counted as dissertations.

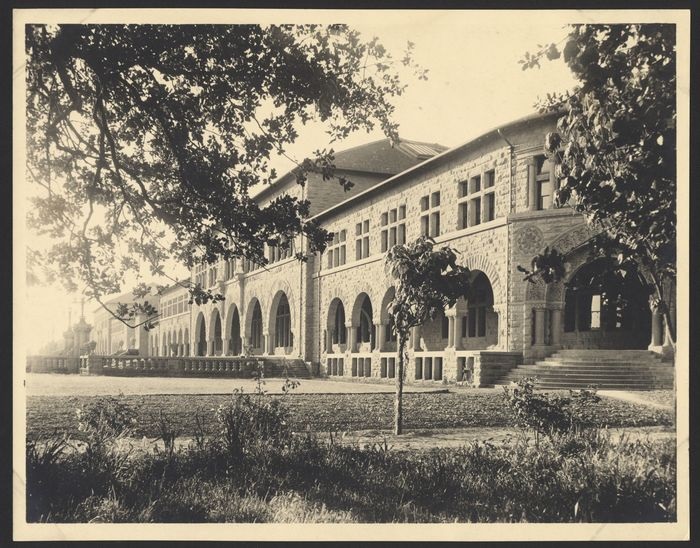

But at the University of Michigan, an emigrant scientist organized a summer school of mechanics. “The expectation was that young faculty at other American universities would want to use their summer vacation to take courses usually required in doctoral examinations,” he explains in his memoirs. The idea turned out to be very popular. In the first summer, in 1929, fifty scientists from all over the country came to study. Timoshenko’s calculation was correct: the number of doctoral engineers at the University of Michigan began to grow. And he himself will regularly give reports at summer schools, even when he becomes a professor at Stanford.

Stanford University Physics Department 1930s

The scientist began to implement another important thing for American engineering science back in Pittsburgh. He decided to organize the Section of Applied Mechanics at the American Society of Mechanical Engineers to publish and discuss specialized scientific works. He managed to infect Westinghouse chief mechanical engineer Eaton with this idea. But from the very beginning it was decided not to confine ourselves to one corporation and to invite representatives of General Electric.

And again Timoshenko found what was missing in American engineering science. Section applied Mechanics, launched at the end of 1928, quickly gained popularity and became an important platform for scientific discussion. And its journal, the Journal of Applied Mechanics, is the most authoritative publication in this field.

The Great Depression began, but the professor survived it safely – from the position of an outside observer. The university cut and then completely stopped paying professors’ salaries, but Timoshenko also worked at Westinghouse. On the way to Pittsburgh, he was often the only passenger in the sleeper car. At the height of the crisis, the scientist went to two congresses in Europe, traveled to France and outlined a plan for a new book, “Stability of Elastic Systems.”

In 1933, he completed six years of teaching at the University of Michigan, and Timoshenko received sabbatical – a paid six-month vacation. He went on a long trip around the Old World and even saw a Nazi rally in Germany. “Some people and children, obviously schoolchildren, were marching through the streets in military order. There are a lot of Nazi party flags everywhere. It was reminiscent of the demonstrations of the Bolshevik times in St. Petersburg,” he later noted in his memoirs.

In the fall of 1934, Timoshenko was invited to the University of California for a month as an outside lecturer. And from 1935 they began to call for good. Almost simultaneously he began to be invited to Stanford University. The scientist chose Stanford.

Having moved to the other end of the country, the scientist, to his great joy, got rid of his job as a consultant. Besides, he liked Stanford students better. More educated, not so rude, from wealthy families.

The outbreak of World War II found the scientist on another trip to Europe. But in America things went on as before. And in his free time from lectures, Timoshenko wrote a new book – on the statics of structures. “American books on this issue seemed to me unsatisfactory,” he explained. “American authors taught “how” the calculation should be carried out, but the question “why” this calculation leads to the desired results remained unclear.”

War engulfed the entire Old World. But until the end of 1941 and the attack on Pearl Harbor, it was not felt at all in American universities. Then the classes thinned out. All healthy and undeferred students were drafted into the army.

Military-industrial programs were developed. Timoshenko either read reports on special departments of the theory of elasticity for aircraft engineers in Los Angeles, or advised the Navy Department in Washington. Then he gave evening lectures for defense industry engineers. The scientist turned 65 years old, but contrary to accepted rules, he was left at the university.

In 1946, mobilized students began to return. And US engineering was on the verge of great changes. State funds were allocated for the development of engineering education. Then, on Timoshenko’s initiative, a department of research mechanics appeared at Stanford. On his next trip to Europe, the scientist explored the mechanical laboratories of defeated Germany and lured the best professors to work in America.

Timoshenko’s classes at the university became less and less. In the new department, he taught only two courses: “Mechanical properties of building materials” and “History of strength of materials.” The second area gradually became the main area of his scientific interest.

He devoted all his free time from teaching to his historical book, which would be published in 1953. And on all my trips around Europe, I bought old volumes on mechanics from second-hand book dealers.

In 1955, Timoshenko finally retired. Although he was already 75 years old, the university administration tried to persuade him to extend his contract. But the professor refused. “All the courses I taught were already printed. And repeating in lectures what a student could read in a book was of no interest,” he explained.

In 1957, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers established a medal named after Stepan (more precisely, in the English version – Stephen) Timoshenko. It is awarded annually for outstanding achievements in the field of applied mechanics. And the first laureate was, naturally, Timoshenko himself. The certificate for the medal explained that the scientist was “the leader of a new era of applied mechanics.”

The elderly professor received many honorary awards and titles in those years. Until his election (immediately after his trip to the USSR) as a foreign member of the USSR Academy of Sciences. “The fact that I was once elected to the Academy by its pre-revolutionary composition was no longer mentioned,” Timoshenko remarked sarcastically.

The scientist was widowed back in 1946. His daughter, Anna Timoshenko-Herzelt, lived in Wuppertal, and the retired professor visited her every summer.

And in 1964, he broke his leg in Switzerland and did not return to the USA, but moved to Germany to live with his daughter. He died in her arms on May 29, 1972. A year before, the professor managed to prepare and publish his latest book, “Mechanics of Materials.”

Timoshenko published his Memoirs in 1963. There he honestly admitted that he was still not sure whether he did the right thing by moving to the USA.

“Having engaged in the training of engineers suitable for the theoretical study of technical problems, I wrote a number of courses that were widely used. But I did little new in America. Whether this happened because I was busy with practical work or because I was already about forty-five years old and began to grow old, I don’t know,” the scientist stated.

Text author: NIKITA ARONOV

References:

1) Timoshenko Stepan Prokofievich. Memories, Paris 1963.

2) Isaac Elishakoff. Who developed the so-called Timoshenko beam theory?, Mathematics and Mechanics of Solids, August 12, 2019

3) Vernadsky V.I. Diaries 1917-1921. Kyiv, 1994.

5) Stephen Timoshenko – path-breaking professor of applied mechanics, Stanford

Nikita Aronov 7.04.2024