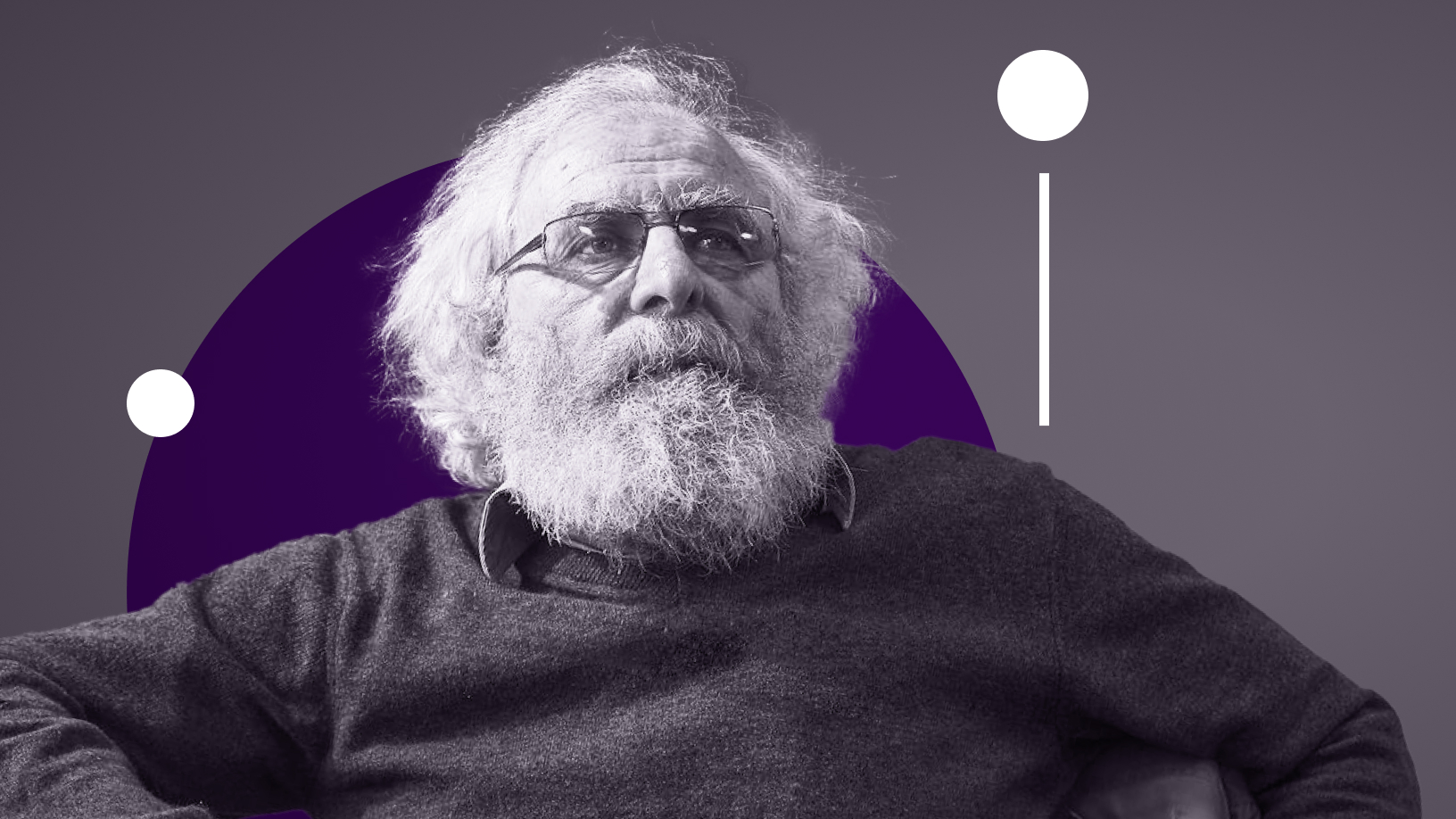

The University of Ljubljana has opened a new graduate program with the support of Google Quantum, which will accept students including: including from Russia. Physicist Mikhail Feigelman explains why the American corporation needed a new project in Slovenia and what is special about this program. In an interview withT-invarianthe describes dangerous trends in modern science and talks about how to create an “island of academic intelligence.”

Mikhail Feigelman – theoretical physicist, Doctor of Physical and Mathematical Sciences, specialist in the field of quantum physics of condensed matter and the theory of superconductivity, professor at MIPT, honorary member of the American Physical Society (2008). From 2003 to 2018 – Deputy Director of the Institute of Theoretical Physics named after L. D. Landau RAS, from 2003 to 2023 – Head of the MIPT basic department “Problems of Theoretical Physics” at the Institute of Physics named after. L.D.Landau RAS. Since 2023 – research fellow at Nanocenter at the Institute of Physics in Slovenia and coordinator of the graduate program at the University of Ljubljana.

Quantum physics in Ljubljana

T-invariant:How did the new project come about in Slovenia?

Mikhail Feigelman: We came up with the project together with my old friend and co-author Lev Ioffe, who has been working in America for a long time and is involved, in particular, in quantum physics calculations. We were looking for a small European country where we could gather young people, both those who fled Russia and, generally speaking, any others who would be interested in studying physics, and not just “building an academic career.” The last one has made me sick for a long time. And then the choice is not very large.

Firstly, this should be a place where, on the one hand, there is already good quantum physics of condensed matter, on the other hand, there is no excessive aplomb like “we don’t need anyone external” ” And, on the third hand, we were looking for a place where we would not be constrained by the reluctance to deal with immigrants from Russia, no matter who they were. And if you look at the intersection of all these conditions, it is not wide. Therefore, Lev turned to one of the Slovenian professors who collaborates withGoogle Quantum, and it quickly became clear that Slovenian physicists were quite interested in such a project. They liked the idea that they would have a small number of specialists from our field who would recruit young people and develop this direction. Initially, we wanted to immediately launch a new master’s program in quantum physics, but the University of Ljubljana advised us not to rush: “It takes a long time to open a master’s program, let’s start with a graduate program, and then we will move on from there.”

T-i:Your program is intended for both theorists and experimenters. Is there a base for them in Ljubljana?

MF: It’s still small. But we have provided how to solve this problem. Our PhD program includes the possibility that a PhD student chooses a supervisor not necessarily in Ljubljana, but, for example, in Grenoble, Karlsruhe or Delft. He studies part of the time in Ljubljana, and part of the time he works where he has agreed on scientific supervision. The peculiarity of the experimental part of the program is that there are still few leaders in this particular direction (although they certainly exist), but we have found a way to raise these people.

T-i:Quite a complex organizational structure?

MF:Yes, which is why it should be implemented, for example, in France or Germany seems completely unrealistic. And in Slovenia, the scientific bureaucracy is not self-sufficient, it is mainly subordinated to common sense. For example, we were able to agree that a graduate of a bachelor’s degree from MIPT or the physics department of HSE can apply to this program, because the volume of this bachelor’s degree almost covers the 5-year European master’s program.

We have already accepted five people in 2023, four of whom are Russians. At the same time, we felt interest in our initiative not only from university professors. There are two institutions here that are located across the street from one another: the university’s Faculty of Physics and the Josef Stefan Institute of Physics, which belongs to the Slovenian Academy of Sciences. The distance between them is about a hundred meters, which facilitates cooperation. In the bowels of the Institute of Physics there is a Nanocenter. This is a real nanotechnology center that works at the request of workers. If someone needs to make “nano-products” e” and encountered problems with stages that require complex equipment – pay, and qualified people using the Nanocenter equipment will perform these stages. This is an extremely efficient institution, partly because it is led by Dragan Mihailovic Dragan Mihailovic – a person very qualified in both physics and management. And partly because the status of the Nanocenter is a non-governmental non-profit scientific organization, which makes life much easier in all respects.

Our program is based on this collaboration.

Faculty of Physics, University of Slovenia in Ljubljana. Google view

T-i:Why does Google Quantum need a “candle factory” in Ljubljana?

MF:There are many academic groups that, to one degree or another, solve problems that are interesting for Google Quantum. The fact is that creating a quantum computer is a project of enormous complexity. There are many teams in different countries working on it, they collaborate with various major “players” in this area (Google, IBM, some others). There are problems related to this area of physics that are of interest to corporations, but not enough to include them in their own current work plans. Then a cooperation agreement is concluded with an academic group that is interested in such a task for some reason. For example, this kind of collaboration between Google Quantum and an experimental group at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology has been going on for a number of years. There are other similar examples. In addition, corporations also need smartpeople to work for them. Therefore, they continuously select young people. The idea that there would be another, albeit small, place where graduate students would be accepted based on a real exam at the entrance, and not on a resume and recommendations – everyone liked this idea.

T-i:Does this mean that students are admitted to this program differently from other graduate students at the University of Ljubljana?

MF:Exactly. They are accepted based on two parameters. The first is an exam for theoreticians or experimenters. But in both cases, people must solve a certain number of problems and explain what they actually solved. The exam takes place remotely, fortunately telecommunications allow this to be done at any time, in a convenient way.

The second is the general requirement of the University of Ljubljana (not how it’s typically done in the West): a graduate student is finally accepted when he has agreed with one of the supervisors that this supervisor will accept him . It’s not like we’ll enroll you, and then you’ll spend a year figuring out who your supervisor is—nothing like that. In case there are some scientific supervisors who do not have official status at the University of Ljubljana, a configuration is provided that there is a scientific supervisor, and there is his co-supervisor from the university who agrees to fulfill this role, and they work together with the student.

Josef Stefan Institute of Physics. Nebojša Tejić, STA

T-i:And the money? After all, if a graduate student has a co-supervisor in Karlsruhe or Grenoble, he needs to periodically travel around Europe. Do your graduate students have increased stipends?

MF:The scholarship is approximately the same as the usual Slovenian one. You can find extra money for travel, it’s not a big problem. The non-triviality of the decision lies in the fact that the Slovenian Education Agency allocated a whole chunk of money for a scholarship for foreign graduate studentsof this program. Again, this differs somewhat from normal practice. There is no such condition that a professor can take on a graduate student only with his own grant. In Slovenia, a supervisor can hire a Slovenian graduate student with money from the Ministry. However, in the case of our program, we managed to ensure that the Ministry of Science allocated money for nine foreign graduate students per year.

T-i:Then what does Google pay for?

MF:For the teachers for these graduate students. In particular, I and two of my colleagues are paid from the money transferred to Nanocenter from Google. Accordingly, we work on scientific problems that are interesting to Googe Quantum – it’s similar to a regular scientific grant. For now this concerns theoretical research, but we hope that this cooperation will be expanded to the experimental area.

T-i: PhD students will be associated with Google after defending their PhD?

MF: They don’t have to, but they have the opportunity. There is a good opportunity to go in this direction even before defending your dissertation. There is a well-developed system of internships for students. When a person is hired for an internship for two summer months, they give him a task, he completes it, and he gets paid for it. And people look at each other: who can do what, who can be useful. This is not very formalized. The main decision is made based on how, in fact, some scientific interaction develops or does not develop.

T-i: Do you have a plan to increase the number of PhD students?

MF: You don’t need a lot of these people. Moreover, I must say, I am glad that in all conversations with local colleagues it sounds like: we don’t need a large number, we need smart people.

T-i: What do you mean by “sensible”?

MF: These are people who know how and want to solve complex problems. Who first think about what interests them, and then think about how they will make a career out of it. In modern times, these are white crows.

T-i: Still, no matter how much a graduate student today is burning with new tasks, after PhD he enters the global academic market, who plays by certain rules. Do you think that these rules partly contradict the very essence of science? What exactly?

MF: Yes, this is a big problem: it doesn’t even partially contradict, but in the main thing. In short, these rules require abandoning interesting (sometimes few) topics of work and sailing in some massive directions, spending efforts mainly on competition with those swimming nearby, which is quite disgusting and ineffective.

T-i: So, your graduate students can say: “Mikhail Viktorovich, you taught us solve not fashionable, but important and complex problems, and we solved them. But if we continue to do this, we will become outsiders, losers. We won’t be able to get big grants. And this means that we will not have money for the next complex and important tasks. We will find ourselves on the academic margins.” The likelihood that they will run into this is quite high?

MF: Yes, and this is one of the frequent subjects of conversations with various representatives of this young generation. It’s true. And I answer them quite honestly that the situation is really bad, and that one can only hope that a sparse but connected network of such people and places where their abilities will be appreciated remains. There are people, and there are not so few of them, who manage to stay in this ridiculous “market” for the sake of scientific results in the old sense of the word, and they are interested in creative, strong young employees no less than in grants. On average in the academic environment, the concentration of such people is small. But the arithmetic mean does not necessarily determine fate. In general, we are accustomed to achieving a lot of things not at the average level, but using rare fluctuations. I don’t see any other way.

T-i: If you tell them this at the entrance, do you risk scaring off young people?

MF: Of course. But this is the reality. And I know a lot of smart guys who simply left physics for financial mathematics: they exist there quite successfully. This is also a choice.

T-i: Do you have the feeling that in Russia students in recent years have become more pragmatic from the point of view of career growth?

MF: Yes.

T-i:What year did this start?

MF: It started gradually. About 10-15 years ago it was already quite noticeable. Until a well-known moment, I could still tell students: “Think about America for yourself. I won’t tell you anything particularly interesting. But in Chernogolovka they will always hire you if you work well.”

T-i:In your opinion, is the substitution of goals in the scientific world, when a career becomes more important than the science itself, a global problem? And at what point does this happen – at the master’s level or when a person gets to Ph.D.?

MF: The fact that this is a global phenomenon is absolutely certain, although this does not mean that it manifests itself in all universities with the same force. But it really manifests itself everywhere, including in Russia, and in rather ugly forms and at all levels. I know a lot of people in Moscow with whom twenty-five years ago I had a common understanding of science, and I considered them highly qualified physicists. Now, as I understand it, they still have their qualifications, but their views on life have changed.

T-i:Do you differ in your assessment of the war in Ukraine?

MF: Not only in connection with the war. These people changed even before the war began. Because this bad system of turning science into a “career” puts pressure on everyone, and few are able to resist it. Especially under the current government in the Russian Federation.

T-i:When did this happen?

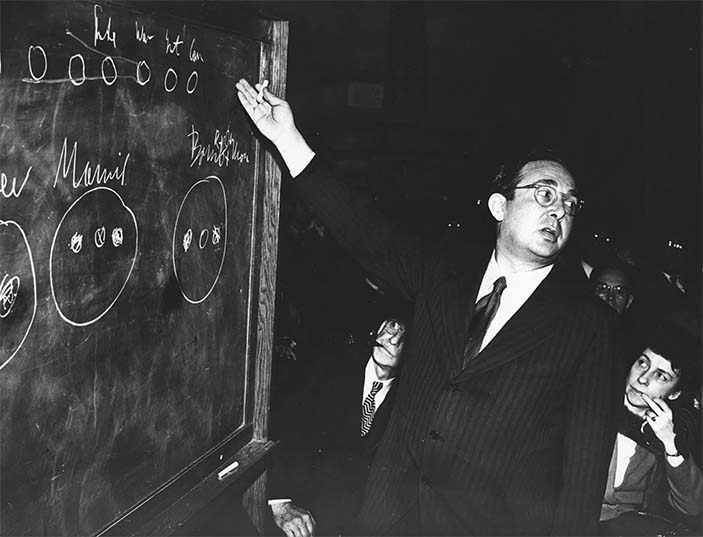

MF: I think that in the whole world this is the result of more than half a century of evolution of a very democratic and progressive grant system, which was introduced in order to citizens adequately assessed who was worth what in science. Some smart people sensed what this meant at the very beginning. For example,Leo Silard already in 1948 I understood what this would lead to. He described it in artistic form here.

Leo Szilard explains the process of nuclear fission. Argonne National LaboratoryArchive

It led, not immediately, but over fifty years, to sad consequences. Another, no less important reason is that the results of scientific activity can be assessed on the merits very slowly, if they are not related to any specific applications. Therefore, the criteria for evaluating current professional work are distorted. In this sense, the situation with those who work, at least partially, on some large and complex project is better, which, in fact, is illustrated by the history of Google Quantum’s cooperation with academic groups.

T-i:Here you come, say, to a university or research center. How will you understand that this place is dead? Or don’t you even need to come there?

MF: You can read articles (in my field, of course, I’m not familiar with all physics). If I read them more or less carefully, I will understand. But one of the signs of the disease is that a huge proportion of people suddenly begin to engage in one fashionable topic. It may even be a worthy topic. But as soon as it becomes fashionable, hundreds and thousands of people flock there and write most of the articles and grants on this very topic. This has nothing to do with doing science anymore. These collective movements of the masses create a terrible effect: they replace scientific interest with career and financial interest. Instead of science, some kind of perverted version of business arises. It’s not that it’s bad that this is a business, but that it’s just perverted. Moreover, I emphasize that these topics themselves, leading to a surge in fashion, may be reasonable (this is not always the case, but often so) – but what is unreasonable is that “everyone who is rushing to deal with them can stand on its feet.”

T-i:But about fifty years ago, when the grant system was being formed, there were topics that were considered not fashionable, but very important. And since this is an important topic, now we will all tackle it together and solve it. And it worked. Why does it look different now?

MF:Perhaps because the number of scientists among the people has increased tenfold. That is why such collective phenomena began to arise. These are no longer individual specialists who know everyone, but some kind of hydrodynamic flows among a population of scientists.

T-i: Do you think that, in general, humanity does not need so many scientists? And so they demonstrate their importance and usefulness?

MF:I suspect so. In addition, there is the problem of clarifying usefulness in basic science. The objective criterion was usefulThere is no value in someone’s job if that job is to bake pies and sell them immediately: the market will sell out. Boots can also be made and sold. Again, we get a quick answer: who makes good boots, and who is “so-so.” In the case of fundamental science, this does not work. It is impossible to find out directly through the market what will be useful and what will not, because this requires much more time than it takes to make management decisions. Therefore, management decisions have been made for quite a long time in all countries by people who, in fact, do not understand anything at all about science. Because of this, they invent all sorts of quantitative criteria, who publishes how much of what, how they are referred to, and all that stuff.

T-i:However, fifteen years ago it was you, together with Boris Stern, the initiator of the project “ Who is who in Russian science”, developed “Corps of Experts”, where quite clearly used quantitative indicators to assess the qualifications of scientists. Although you are not officials.

MF:That’s right, we used quantitative indicators at the input, but we never used them automatically. We used them for primary selection. And then, with the hands and heads of different people, an assessment was made of what had turned out. We said from the very beginning that it is pointless to automatically use all this numbers. If this happens for a year or two, it’s not so bad. If this happens for several decades, the result is very bad. Then the meaning of doing science directly becomes completely secondary, in principle, even unimportant for the functioning of the “evaluation system.” Because the evaluation system can greatly distort the very essence that it is intended to evaluate.

T-i: It turns out that, on the one hand, officials have a need to evaluate activities scientists, but by definition they cannot be good at science: it is none of their business. On the other hand, scientists have a need to feed themselves. And in these two needs, on both sides, a certain system of mutual offsets is born. Some say: “We want clear numbers from you.” And others answer: “So we will customize for you what you want from us.” And in this dialogue, the most important thing eludes – the scientific search, the scientific task and the very understanding of where the whole scientific train is going next. And here the question arises: why have scientists still not come up with an assessment system that would somehow retain the essence of science and satisfy the needs of officials? After all, they are not that complicated. Is it not possible for officials and administrators to offer some kind of “cheat sheet” that would not devour the scientists themselves? So that there is no need to generate an industry of “junk” magazines and other things?

MF:The plan of salvation is unknown to me. Previously, when I was at my usual place of residence, I spent a lot of time inventing all sorts of useful measures in this direction. But these inventions of that time have now lost all meaning. And in my current position as a fugitive Russian Jew, it would be ridiculous to discuss these topics at all, because there is absolutely no one to listen to such reasoning.

T-i:There is no one to listen to the plan to save the essence of science?..

MF:I understand the plan of salvation only in some very local sense. I see that there is some kind of statistically insignificant, but not zero network of people who understand what they actually do and why they exist. And there is only one way out – to support this network and teach students. This is not a revolutionary path..

T-i:Even ancient, antique.

MF:Ancient. But I don’t see any other way for science to survive.

Childhood disease of leftism

T-i:What do you think about such a phenomenon as Academic Left? Nowadays, in many universities, belonging to an academic community implies sharing certain ideological views. Today, their set is in a certain sense formulated as the DEI curse – Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. But he comes from the 1960s.

MF: I understand what you are saying. But I have a strange situation: I almost never meet such characters. I guess I have disgust for this written all over me…

T-i:But the phenomenon is powerful, it’s hard not to notice, even more – impossible pass.

— Olya, here I’ll tell you an old story. I had a very good friend- French physicist Miguel Hosio. In 1968 he was 25 years old. He was a young engineer, coming from a rather poor family in the south of France, who managed to get an education and work his way into the middle class. He worked all his life, as they say, with all his might and always. I once asked him how he felt about the events of May 1968 in Paris. Moreover, he himself had socialist views to a certain extent. So Miguel told me: “I perceived it as a revolt of the children of the bourgeoisie for the right to do nothing.” And as we now understand, this rebellion was successful, it won.

T-i: Oh, if today “children” just wanted to do nothing, it wouldn’t be so bad – they would just need to be supported. The problem is that the “children” have grown up and dictate the rules, do not allow others to work…

MF: They don’t allow it, because their views have evolved. This was in 1968, and since then the concept has evolved. And it has developed to the point where it is now unclear who will really do the work. And even to the point that at Princeton University, a portrait of Richard Feynman is being removed from the wall – for “politically incorrect behavior” in the distant past. And somewhere else they demand that Newton’s laws not be named after him, “for the purpose of decolonization policy.”

T-i: Not long ago a scandal broke out: the organizer of the Latvian developer conferences DevTernity and JDKon Eduard Sizovs invited fake developers and even created fake accounts for them on social networks and got them subscribers. The reason is clear: there are formal gender requirements for the composition of participants, speakers and plenary speakers. And if at the level of participants and speakers it is somehow possible to cope, then at the level of plenary speakers it is always a problem with women. It is known that astrophysicists and bioinformaticians have similar problems. There are strong women scientists, but there are not as many of them as is required to “plug” gender quotas at all conferences, and they cannot physically have time to come everywhere. How is it going in your area?

MF: I have repeatedly organized small (60-80 people) conferences in Chernogolovka. There, of course, there were no “quotas”. I also participated several times in organizing similar conferences in Europe (Holland, France). There was this motive, but it was possible to deal with it quite easily. The organizers specifically remembered whether there was any other reasonable lady who could beinvited, but the unreasonable ones were not invited. The “quota” was not completely filled, but it worked out.

T-i:Do you have an understanding of how a humane desire to protect the oppressed, the outcast, to give him equal rights and opportunities with the majority, has led to the fact that now the adherents of this humanism are defending murderers and rapists from Hamas? How did a vulnerable person with a transgender transition end up separated by a comma and a sadist yelling into the phone “Mom, congratulate me, I just killed two Jews!”? In a recent letter, billionaire Bill Ackman, a Harvard graduate, is one of those who refused giving money to his home university because of its erroneous personnel policies, called the outbreak of anti-Semitism at the university only the tip of the iceberg, “canary in the mine”.

MF: Akman is doing absolutely the right thing, in my opinion. And very effective in his actions. “Hit with the dollar” is the clearest message in this situation. However, I cannot trace the genesis of the phenomenon you asked me about. I can only say that a month ago something happened at the University of California at Santa Barbara. There, the student senate (a very real student body) voted with a majority of about ¾ in favor of an official resolution condemning Hamas. This caused astonishment in the academic establishment. And this affront was caused by my grandson, Efrem Shalunov, a computer science student in Santa Barbara. This young man has been involved in a fair amount of social activity since adolescence. For him, this activity is accompanied by real common sense. From the very beginning, his colleagues dissuaded him from promoting this resolution, and he himself understood that the matter was risky, but he decided that he was ready to take the risk. I invested heavily in this business and won. Created, so to speak, a precedent. These are the guys I hope for.

Russian science: sanctions now, reforms later

T-i: The Landau Institute, where you worked for decades, came under US sanctions. Do you know the reasons?

MF: No.

T-i:Do the scientific activities of the institute have anything to do with increasing Russia’s defense capability?

MF: No, and never had. As soon as it became known that the Landau Institute was included in the sanctions list, I suggested that the directorate of the institute try to challenge this by hiring American lawyers, but they did not. However, they can be understood: for those who work in the Russian Federation, these sanctions mean nothing in practice. They hit students and employees who left because of the war: they are systematically not given visas to the United States, even those who have Ukrainian citizenship. In other words: people who left Russia because of the war and whom their American scientific colleagues want to see are not allowed there by the bureaucracy of the State Department or the American intelligence services (I don’t understand these details). Fortunately, in Europe I have not yet seen manifestations of the same nonsense.

Institute of Theoretical Physics named after. L.D. Landau RAS. Trinity Option

T-i:Have many left your institute?

MF: Not very much, as far as I know. Most of the people who left were young people who had recently completed their degrees, graduate students, and undergraduates. And of the adults, maybe a couple more people.

T-i:You have an affiliation with the ITF named after. Landau left?

MF: Conditional. I’m on unpaid leave.

T-i:When you publish, you indicate the affiliation of the ITF. Landau?

MF:I bet. At the same time, the editors of Physical Review and some other journals regularly send me articles for review.

T-i:What do you think about the future of Russian science? Now in the academic community with Russian roots, two opposing trends are noticeable. Some believe that a quick regime change in Russia is inevitable because the situation is too unstable. Therefore, at the conventional hour X, Russia should not be left without ideas, without reformers, without scenarios for overcoming the crisis, as it was in the early 90s. Thus, we need to work on Plan B right now, including on the reform of Russian science. And there is the exact opposite approach: changes will begin so soon that we will not live to see them. And if we live, we will no longer be actors, but rather elderly witnesses. So there is no point in investing in empty things. Who are you with?

MF: I had thoughts about what I would have to do when such an opportunity arose four or five years ago. I tried to discuss them, took some even small actions, but somehow I did not find a noticeable number of interested people. And now I don’t think anything about it, because I understand that I won’t live to see it. But what seems quite obvious to me is that the result of the inevitable changes will be such a level of bedlam that for a noticeable number of years in Russia no one will care about science.

T-i:Will there be a 1990s effect again?

MF: It is likely that it will be much worse. Well, besides, in addition to the criminal trash that now rules the country, there are a large number of citizens who have simply adapted to existence in this aggressive environment. And this device is not in vain. I can’t imagine how they will want to listen to advice developed by their former brothers who wrote programs for overcoming the crisis somewhere in Berlin or Paris. Even if these programs are very good. Moreover, when it comes to science, we need to rewind much further, to pre-war problems. Who will do this? Circumstances, structures, relationships have developed. Who can change them? Although a few years ago I started a conversation with colleagues: “Listen, there was a Polish experience: Solidarity in 1980 did not arise out of nowhere.” Therefore, the very idea of preparing for changes in advance is close and understandable to me. But in relation to my own professional activities, I don’t see any prospects now. The most useful thing I can do iso gather as many smart young people as I can and give them the opportunity to really work professionally, wherever they are. I want to give them the opportunity to do science, and not the accompanying quasi-business. And if one of them, after this imaginary moment X, suddenly decides to restore something in Russia, great. But for this there needs to be someone to restore it. I’m unlikely to do this myself, because I’m already old. But in any geographical location I will try to preserve the remnants of what I myself was taught. A number of my former students also showed interest in our initiative and are ready to participate in it. This is no longer enough.

T-i:Now there is a wave of “spy” and other repressive trials against scientists. People outside Russia constantly ask me: “Why is Putin shooting himself in the foot, because in a country at war, scientists are needed.” Do you have a version of the answer?

MF: It’s ridiculous to look for logic in the actions of this system. Logic implies that there is some kind of center that needs to achieve some goals… There are none.

T-i:Well, in such cases, people rely on the Soviet experience, where scientists were quite a pragmatic attitude. And many people think that since the smell of the USSR is in the air, this attitude towards science should return.

MF: What we are seeing in Russia is not a return to the Soviet system. This is a completely different system. Moreover, it is much worse than the late USSR that we saw in our youth.

T-i:What do you see as the difference?

MF: In the absence of any ideology other than the retention of power by the top. This is a thoroughly corrupt, essentially criminal system that has no idea other than “you die today, and I die tomorrow.” All that “patriotic” nonsense that they proclaim is just a situational invention to mobilize the population, nothing more.

T-i:The Soviets had everything seriously, but these…?

MF: A nightmarish, deadly parody. Why are they imprisoned? Because it’s planting. Because some department of the relevant department has learned to make its own business out of this and improve its performance.

T-i:Is it being planted to increase the FSB’s “H-index”?

MF: Exactly. The same thing, only worse in terms of results. Individual elements of a large and complex system optimize their personal results, regardless of the relationship in which this is with the imaginary properties of the system as a whole.

I had a conversation in the spring of 2022 with intelligent colleagues twenty years younger than me, and they remarked: “When you were young, you worked in Soviet conditions and, it seemed, it even worked out well. This is how we will have to work now.” I tried to explain that they would face something completely different. These will not be Soviet conditions at all, and in these new conditions they have no chance at all in the long term. Because the Soviet academic system was largely based on the fact that people, unless they were shot, live quite a long time. Both these people, educated at the beginning of the twentieth century, and their direct students were serious scientists. They were the basis of the Soviet academic system. But she couldn’t hold on forever – she eventually ran out. What I dealt with in my youth were the remains of the archipelago. And the authority of these serious scientists was considerable.

T-i:Do you mean authority in the eyes of the authorities?

MF: Authority in the sense that they could decide what to do and what not to do. Who to hire and who not to hire. And these decisions were made according to scientific criteria; at least at the Landau Institute for sure, and in some other places too. But gradually these people faded away simply as life went on. And in each next generation the system took its toll. Now there is simply no one who: a) has the opportunity to say a word; and b) had something to say. There are none left. In addition, there is simply no one to say: the government is insane. So, even if there is some kind of restoration of science in Russia, it is impossible to predict how and due to what it will happen. Someone will have to start all over again.

Text: Olga Orlova

Olga Orlova 31.01.2024