The first «brain drain» from the Russian Empire began at the beginning of the last century. It was the time when specialists and university professors began to leave the Empire destroyed by revolutions, the First World War and the Civil War. At that time there were no traditional routes for Russian emigrants. They were scattered all over the world, looking for opportunities to realise their ideas in different countries. As part of the “Creators” project, T-invariant, together with RASA (Russian-American Science Association), is beginning to publish a series of biographical essays about people from the Russian Empire who made significant contributions to global science and technology, about those to whom we owe our new reality. The first essay is dedicated to Selman Waksman, Nobel Prize winner and discoverer of the antibiotic streptomycin.

At the end of the 19th century Novaya Priluka was an ordinary Jewish town (more precisely miasteczko) in Berdichev uezd of Kiev Governorate. The town appeared like a tiny dot in the endless black earth steppe. One of the most famous microbiologists of the 20th century, Selman Waksman*, was born and raised here. He spent most of his life far away from here — in the other hemisphere, in the United States, in New Jersey. But when he was awarded the Nobel Prize for the discovery of streptomycin, the first cure for tuberculosis, Waksman took words from the Bible as epigraph for his Nobel lecture: “The Lord hath created medicines out of the earth, and he that is wise will not abhor them” (Ecclesiasticus, XXXVIII, 4). Thus, Waksman paid tribute both to the Ukrainian black earth and to his melameds who taught him to read in the Priluka cheder. However, it was not only a rhetorical figure, but also a statement of a scientific fact: streptomycin was indeed obtained “out of the earth,” and from soil microorganisms — actinomycetes.

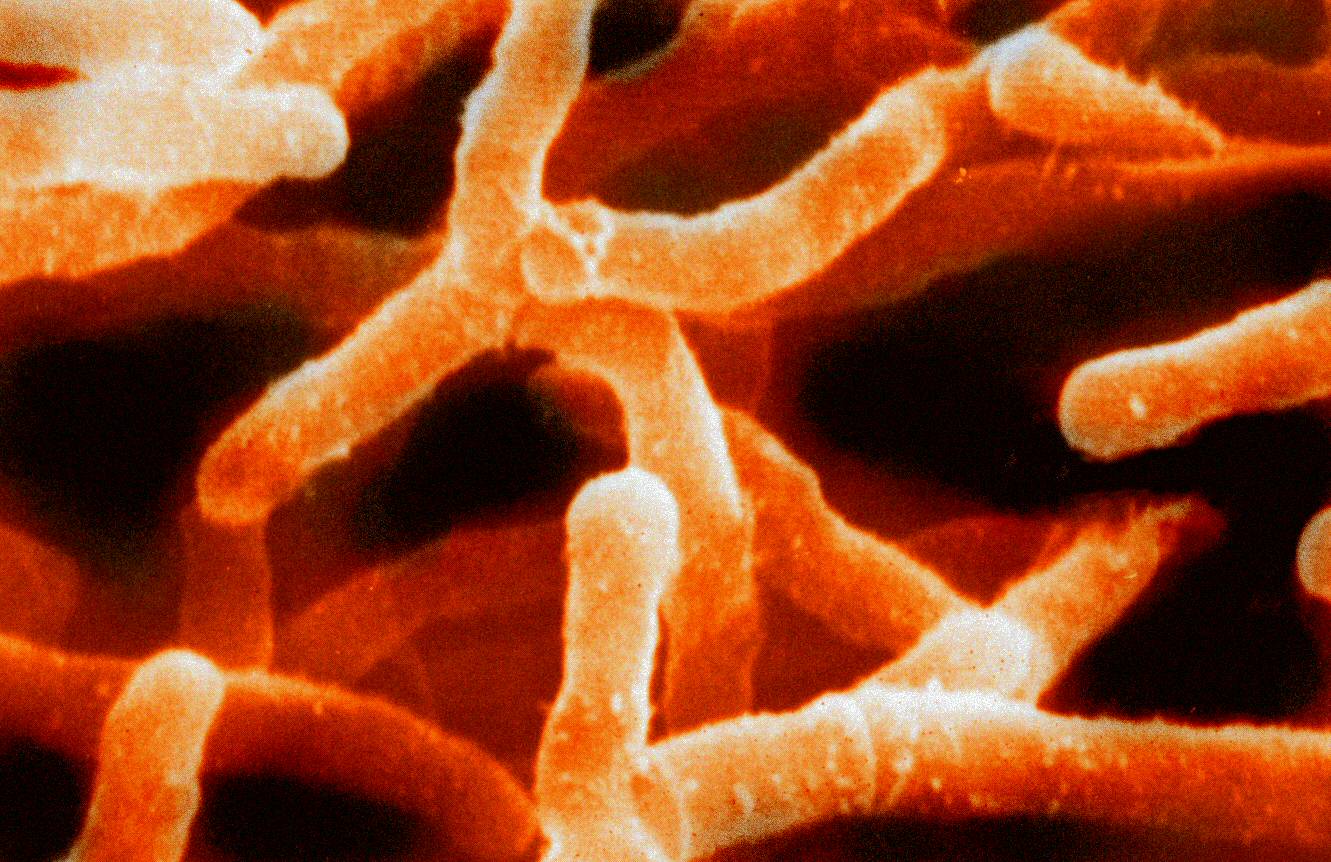

Actinomycetota

Selman Abraham Waksman titled his autobiography My Life with the Microbes. This is also the title of the first chapter of the book. It begins with these words: “I have devoted my life to the study of microbes, those infinitesimal forms of life which play such important roles in the life of man, animals, and plants. I have studied their nature, life processes, and their relation to man, helping him and destroying him… I have contemplated the destructive capacities of some microbes and the constructive activities of others. I have tried to find ways and means for discouraging the first and encouraging the second.” (3)1

As a young researcher, Waksman became interested in a special kind of microbe that lives in the soil: actinomycete. They are strange organisms.

Today they are certainly called bacteria, but in the early 20th century there were significant differences. If they are bacteria, they are rather unusual. Actinomycetes form a mycelium consisting of a mass of branched, filamentous structures. That is, they behave like fungi. This strangeness is enough to arouse our interest in them.

But there was another reason why Waksman became fascinated with these microorganisms in 1916, when he was pursuing his doctorate at the University of California at Berkeley. He found that actinomycetes are capable of suppressing the growth of other bacteria. In his Nobel lecture, Waksman reminded that even then he selected one of the actinomycete species and named it Actinomyces griseus. Waksman noted that this species has antimicrobial properties. But this actinomycete species, which was renamed Streptomyces griseus in 1943 and played an important role in the discovery of streptomycin, was not studied in detail by Waksman in 1916.

It was interest in actinomycetes that led Waksman to systematically search for antibiotics in the late 1930s. The word antibiotic itself was also suggested by Waksman.2

Novaya Priluka

Selman Abraham Waksman was born and raised in the town of Novaya (New) Priluka, in Berdichev uezd of Kiev Governorate on July 22, 1888. Waksman described his birthplace as “a bleak town, a mere dot in the boundless steppes.”. In summer, wheat, rye, barley and oats grew in these endless fields. In winter, the steppes were covered with snow. “The earth was black, giving rise to the very name for that type of soil, tchernozem, or black earth. The soil was highly productive, yielding numerous crops, grown continuously for many years, without diminishing returns.” (17)

Waksman was named after Solomon, the biblical King of Kings, whose name was reduced to “Zolman” in Yiddish (the variant “Selman” already appeared in America). Selman’s father, Yakov Waksman, was a pious man and lived modestly, renting small houses in neighboring villages and in the town of Vinnitsa, which he owned. Life as a pensioner left him enough free time, and he devoted his days to prayer and attendance at the local synagogue. In his autobiography, Waksman describes his father as a wonderful storyteller who loved edifying parables about the sages of antiquity and about the centuries-old history of the Jewish people.

When Selman was born, his father was absolutely happy, but soon he was drafted into the army, where he served for five years. The two were not particularly close, although Yakov Waksman always tried to help his son in any way he could. The truth was — he could not do much.

The most important person in Waksman’s childhood and youth was his mother Fraida Waksman (her maiden name was London). She was educated, especially for a woman of that time. She read Yiddish, spoke enough Hebrew to understand the Bible, and spoke Ukrainian. All of this benefited her greatly.

As Waksman recalls, his mother married late (almost at the age limit of the time — 27 years) because she was too busy marrying off her younger sisters. She built a house (not particularly luxurious, but her own). In it lived her sisters with nephews and nieces and her mother. Fraida was a real Yiddish mame — powerful and responsible. All this kahal had to be fed, and she depended on a small dry goods business for income. And on fair days, which were quite frequent in the Berdichevsky Yezd, Fraida always organized a traveling trade. Her hospitality and care for her sisters and nephews were a great help to Selman in the future when she was no longer alive. In New Jersey he was welcomed and embraced by a cousin who once lived for a long time in Fraida’s house, cradling little Selman and singing lullabies to him.

When his father returned from the army, Waksman had a sister, Miriam. She died of diphtheria in early childhood. Waksman writes that she could have survived, but the cure from Kiev, two hundred miles from home, came too late. Whether or not it would save a sick child is unknown, but Waksman was very upset by Miriam’s death: “As I watched her die,” he wrote, “my childish and observant mind may have speculated on the possible effect of the curative agents upon the disease and the potential salvation of her life. Here for the first time, I was brought in contact with a problem that was later to receive much of my attention.” (29)

in 1952, the same year that Waksman received the Nobel Prize, it was announced that a new diphtheria drug, erythromycin, had appeared. It was derived from actinomycetes, which Waksman had studied so thoroughly.

At the age of five, Waksman joined the local cheder, where melamed taught Jewish children to read the Torah. Then education broadened, and the future microbiologist began reading books of the prophets and studying the Talmud. But Fraida did not give birth to her only son so that he would be limited to these subjects. She was convinced that a cheder was not enough and hired private tutors to teach the ten-year-old boy Hebrew, Russian language and literature, history, arithmetic, and geography. Waksman writes that by the age of thirteen he knew the Bible and Talmud well and was reasonably fluent in Russian. From the age of ten, Waksman began to teach. First, he taught cheder students to read and write, then he began to prepare children from wealthy families to attend secular schools. He began to earn, and this money went to his teachers.

Waksman was preparing to take the exams at the gymnasium. It was difficult to get ahead. And because there was already a percentage norm for Jews: their share should not exceed a strictly defined and small percentage of students, which led to strong competition among the Jews themselves. And because there were no gymnasiums in Berdichev or in nearest Vinnitsa. And the way to the university was just through the gymnasium. Vaksman prepared to take external exams for the first six years of study in order to enter the seventh grade of a gymnasium in Zhytomyr. However, this attempt failed. Waksman took an exam in geography. The teacher who administered the exam asked him: Which river flows in Berlin? Waksman knew the rivers of Germany very well, but he could not remember which river flows in Berlin. He tried to talk about the Rhine and the Elbe, the Main and the Oder, but the teacher was adamant. He needed the exact answer. He did not get it and gave Waksman a “0.” He was not allowed to sit for the next exam. And he was already 17 years old.

20 years later, when Waksman came to Berlin for a scientific conference, he stood on the bridge over the Spree and almost burst into tears. What a small river! How can it be compared with the Rhine! What did this teacher need it for!

Fraida was upset no less than her son. His father had a house in Vinnitsa, which he rented out. And Waksman moved to Vinnitsa to study with stronger teachers. Then he went to Odessa with friends, where he studied with real high school teachers. It was not cheap. But Fraida was not sorry for anything, and Waksman himself gradually earned a little from teaching. Most importantly, the teachers with whom Waksman and his comrades studied in the evenings also took exams from external students. And this time, Waksman succeeded. He was 21 years old. He had a high school diploma. It was possible to try to go to university. Although the percentage for Jews was tightened again, there was still a chance.

And then Fraida died. The father married quickly. There was nowhere to return to Priluka, and there was no need. Waksman had long been called by his cousins who had gone to America. And he decided to change his life drastically.

They left the Russian Empire by train. Three boys and two girls from the town. As the train crossed the German border, they sang, quietly at first, then louder and louder, all the way through the train car, “We have shaken the shackles off our feet. We are entering upon a new world, a free world, where Man is free.”

They believed that a great, free country was waiting for them, that a wonderful new life awaited them: from Novaya Priluka — straight to the New World.

The year was 1910. Waksman returned to Novaya Priluka once again. For 10 days in 1924. It would have been better if he had not.

New Jersey

In the fall of 1910, the ship carrying Waksman and his friends came from Hamburg to Philadelphia. Here the Priluky boys and girls parted ways. Waksman was greeted by cousins and traveled to his family in New Jersey.

His cousin had a small farm and a chicken coop. Today, when we trace very quickly the path that Waksman took step by step, overcoming enormous difficulties, we cannot get rid of the thought that he was literally guided by the hand of Providence. It was on this farm that Waksman first worked with chickens. And here’s what he wrote in 1964: “If you ask who was responsible for the isolation of the particular streptomycin-producing strain of Streptomyces griseus, the answer must be that it was the chicken, because it was she who picked up the culture from the soil.” 3. The strain of Streptomyces griseus from which streptomycin was isolated was in the chicken’s throat.

Waksman spent the first months of his stay in America on a farm. There was little work in the winter, and he studied mainly English: he read English and American literature. What exactly he read, Waksman does not mention in his memoirs. But probably something instructive. He never liked literature without correct morals.

As Waksman writes, in his youth he had an almost perfect visual memory. He could read a page and memorize it. But for this amazing ability, nature took from him a rather harsh compensation: he could not remember well from hearing. Even as a student, he carefully wrote down lectures to read later and keep them in his memory forever.

At the suggestion of his cousin, he visited nearby Rutgers University. There he met Dr. Jacob Lipman, an immigrant from Russia, who encouraged him to enter in the College of Agriculture. Waksman reluctantly agreed. He wanted to study medicine. But I had to come to terms with that: there just was not enough money for medicine.

And again, the hand of providence. Pediatrician Arvid Wallgren, professor at The Caroline Medical Institute and a member of the Nobel Committee, in announcing the award of the Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine, said, “Neither are you a physiologist nor a physician, but still your contribution to the advancement of medicine has been of paramount importance. Streptomycin has already saved thousands of human lives. As physicians, we regard you as one of the greatest benefactors to mankind.” No, Waksman did not become a physician, he did much more: he gave physicians a weapon to fight.

In 1911, Waksman entered Rutgers. He studied diligently and began working with soil bacteria in his fourth year. It was at this time that he first drew attention to actinomycetes. These microorganisms became the main subject of his master’s thesis at Rutgers and his doctoral dissertation at Berkeley (University of California at Berkeley), where he studied and worked from 1916 to 1918. But the first antibiotics were still very far away.

In 1916, Waksman became a U.S. citizen. He married Deborah Mitnick, whom he affectionately called Boboli. He had known her since childhood. She was the younger sister of his friend from Priluka, with whom they had come to America together. Boboli stayed home, but they agreed that she would definitely join them once the young men had settled in normally and could help her. The young people settled in. She arrived. And everything worked out for the best. When a son was born to the Waksmans in 1919, he was named not at all canonically in honor of one of Selman Waksman’s first teachers, Byron Halsted. And Byron Halsted Waksman did not disgrace his last name, becoming a famous microbiologist and professor at Yale.

Waksman returned to Rutgers from Berkeley in 1918. He began lecturing on soil microbiology at the college and was appointed to a specially created position of “microbiologist” at the college’s agricultural station. He insisted that his specialty be called “microbiology” rather than the more traditionally “bacteriology”, because he was interested in actinomycetes rather than classical bacteria.

A search for antibiotics. Go I Know Not Whither and Fetch I Know Not What

Waksman first became interested in actinomycetes in 1915 as a student at Rutgers University. In the decades that followed, he studied their distribution and abundance, their taxonomy, their role in processes such as the decomposition of plant and animal remains and the formation of humus, and their relationship to bacteria and fungi.

Waksman and his colleagues knew of the existence of Streptomyces griseus, the microorganism from which the streptomycin strain was eventually derived, from the beginning of their research on actinomycetes at Rutgers, but its antibacterial properties were not tested for several decades.

In 1924, after several years of soil research, Waksman and his wife spent six months in Europe, where they returned for the first time since immigrating to the United States.

They visited Novaya Priluka. But it was a very hard comeback. Waksman wrote: “The greatest misery that one could ever imagine, the greatest catastrophe that the peoples in Russia have gone through; the greatest experiment in social and political relations of men can hardly express what we have seen (during the last few days).” (145). The Waksmans spent ten days in Priluky listening to family and friends describe their plight: “Each one suffered to an extreme. Many cried like children before their father; they came to pour out before us all their sufferings.” (146). They asked for help. But there was nothing to help with.

However, the main reason for the trip was science. In his autobiography Waksman wrote: “There was no question in my mind concerning the role of microorganisms in soil processes, but there was a certain question that was continuously arising as to whether I was headed in the right direction.” (120).

To answer this question, Waksman visited scientific laboratories in France, Italy, Germany, and Scandinavia, where he discussed methods and research on microorganisms with leading scientists working in the fields of biology and soil chemistry. He returned to the United States inspired by his knowledge and convinced of the need for a comprehensive treatise on soil microbiology. And such a treatise was published in 1927 under the title “Principles of Soil Microbiology.”

In the 1920s and 1930s, Waksman continued his studies of actinomycetes, but his main research activity focused on the soil microbes themselves rather than on their effects on disease-causing organisms. In 1939, there were two events that changed many things. The first was the outbreak of World War II, which led to the need to develop new drugs to combat infectious diseases and epidemics that always accompany wars. The second development, Waksman’s “special stimulus,” was the work of René Dubos, a former student of Waksman’s, who isolated tyrothricin, which kills disease-causing bacteria.

Dubos showed that it is possible to find bacteria that inhibit the growth of other bacteria. Pioneers in infectious disease research, such as the discoverer of the tubercle bacillus Robert Koch, were afraid of non-sterile substances and avoided contamination. Dubos did just the opposite, using a drug literally “extracted from the dirt” to fight infectious diseases. Waksman drew inspiration from this conceptual breakthrough and pushed forward with the search for new agents in soil that were active against disease-causing bacteria. Unlike Dubos, however, Waksman focused not on bacteria but on fungi and, in particular, actinomycetes.

If Sir Alexander Fleming discovered penicillin largely by accident — he noticed that a bacterial pathogen was infected with a mold that had literally flown through the air — Waksman approached the search for antibiotics systematically. He and his students conducted a painstaking, methodical, sequential screening.

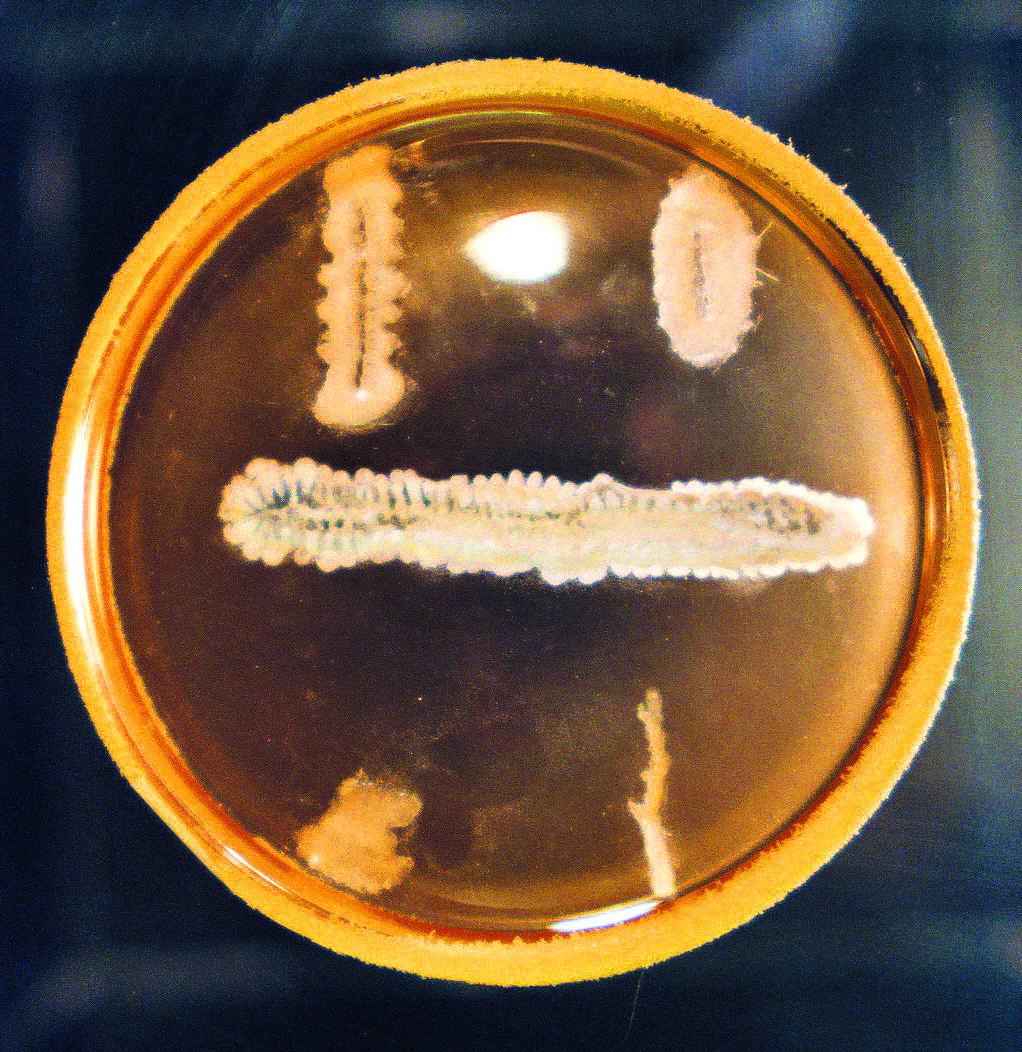

First, colonies of soil microbes were isolated on agar plates. Then these microbes were tested on specially isolated pathogens. It was a long, tedious job as thousands of cultures of various microbes were isolated and then tested for their antibacterial activity against many, many pathogens. Only a few cultures have shown antipathogenic properties. These few cultures were subjected to further testing to identify those among them that would produce germicidal substances in sufficient quantity. And then, from these microorganisms, those that were not too toxic for therapeutic use, i.e., would not poison humans, were selected.

In 1949, Time magazine wrote about Waksman’s discovery of neomycin in an article titled “Man of the Soil”: “People are always asking greying Microbiologist Selman Abraham Waksman, 60, how he discovered the wonder drug streptomycin in 1943. Modest Dr. Waksman… has a stock answer which makes it sound pretty simple. He merely examined about 10,000 cultures, he explains. Only 1,000 would kill bacteria in preliminary tests; only 100 looked promising in later tests; only ten were isolated and described; one of the ten proved to be streptomycin. It just happened that streptomycin was the first effective drug that doctors had ever found to fight tuberculosis.” 4

On the outside, everything actually looks quite simple, albeit laborious. But until clinical trials on humans took place, no one was sure that the discovery had been made and that streptomycin was really something useful and not just another dose of poison that killed bacteria but didn’t make it any easier on humans.

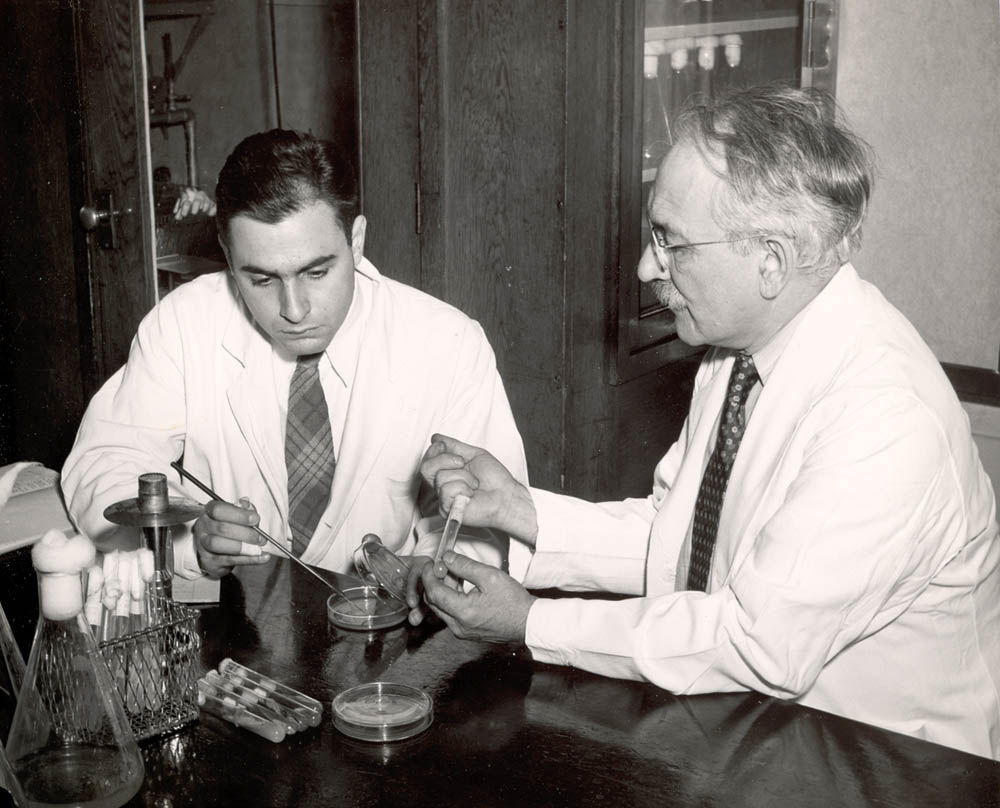

The screening protocol proposed by Waksman to search for antibiotics can be compared to analog multivariable optimization. But there are so many parameters, and they are so weakly formalized, that there is generally no guarantee that the process will converge to an optimal point that will become a true cure. No one could give such a guarantee. And that optimization was found by Waksman’s student Albert Schatz. Of course, it is luck. And it is a coincidence. But as Louis Pasteur said, “Luck favors the prepared mind.”

The Schatz was ready. And it was prepared in the first place by Waksman.

Cross-streaking technology. Actinomycetes (horizontal strip) and various pathogens (vertical strips) are seeded on agar plates. Once the pathogen reaches the actinomycete, an antagonism area is created where the actinomycete inhibits the growth of the pathogen. If the antagonism zone is not present, the actinomycete does not act against the pathogen. There are tens of thousands of such experiences.

Rutgers University Archives.

Waksman’s screening protocols identified about twenty new natural antipathogens, most of which were derived from actinomycetes. It was Waksman who coined the term antibiotics, now in common use, for these therapeutic agents (see Note 2). The first drug isolated in 1940 as part of the first screening program was actinomycin. It was developed by Boyd Woodruff, Waksman’s graduate student. Actinomycin was effective against a variety of bacteria and even a strain of tuberculosis, but proved too toxic for therapy in humans.5

Two years later, Woodruff isolated streptothricin, an antibiotic that was effective against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. 6 Researchers were excited about streptothricin because, as Waksman said in his Nobel Prize speech, it “promised to fill the gap left by penicillin in the treatment of infectious diseases caused by Gram-negative bacteria”

Streptothricin is not only effective against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, but also proved to be nontoxic to animals in initial trials. However, in subsequent experiments, streptothricin was found to still be toxic, but not immediately, but only as a slow-acting toxin, which is why it is not suitable for humans.

The partial success of streptothricin showed that Waksman and his students were on the right track. It was necessary to find a variant that suppressed pathogenic organisms without killing the host organism.

Albert Schatz (left) and Selman Waksman. Rutgers University Archives.

The breakthrough came in 1943 when Albert Schatz joined the team and, building on Woodruff’s approach, found two streptomycin-producing strains of Streptomyces griseus. One of these was discovered by chance when Doris Jones, another Waksman student, examined the tracheal flora of chickens and noted antagonism areas on several plates.

The cultures were given to Schatz, and from one of them he isolated an active strain of Streptomyces griseus that produced an antibiotic that suppressed both gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria. Even more interesting to the researchers was that streptomycin was effective in vitro against Mycobacterium tuberculosis, the “Great White Plague”7

The Trials of Streptomycin

Selman Waksman and his group of students knew from their own in vitro experiments that streptomycin is active against the tuberculosis pathogen. Waksman was aware, however, that his small laboratory at Rutgers University was not equipped for further testing, let alone in vivo trials. So Waksman approached two Mayo Clinic medical researchers — William H. Feldman and H. Corwin Hinshaw — about conducting animal experiments with guinea pigs. Feldman replied on March 7, 1944, that “we are in a position to make such a test” if Waksman could obtain enough samples of the compound.8

Waksman was able to provide the Mayo Clinic with a sufficient number of samples thanks to a tentative agreement with Merck & Company made in late 1939. Under this agreement, the pharmaceutical giant provided a grant to Waksman’s laboratories for antibiotic testing. In addition, under this agreement, the company promised to provide assistance in chemical analysis, to provide experimental animals for pharmacological evaluation of antibiotics, and to provide equipment for the manufacture of promising drugs. In return, Waksman let Merck have all the patents that resulted from research in his lab. If any of the patents were commercially successful, Merck had to pay a small royalty to the Rutgers Foundation (203-204).

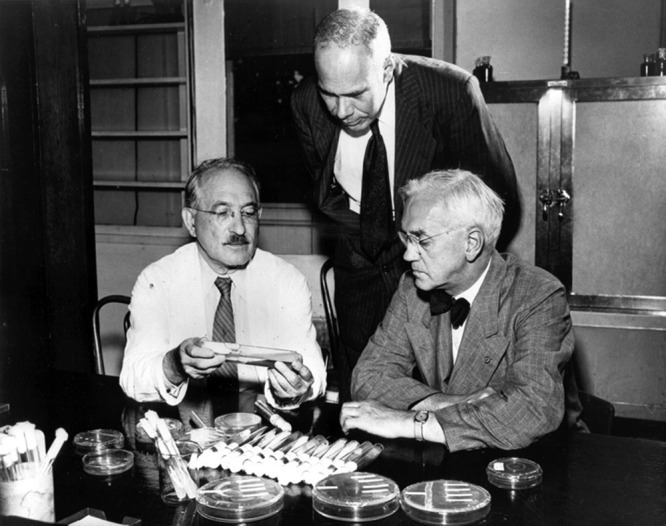

(Left to right) Selman Waksman, Randolph Major (Research Director, Merck and Co.), and Sir Alexander Fleming (Nobel Prize winner, discoverer of penicillin). Rutgers University, 1940s. (Special Collections and University Archives, Rutgers University Libraries.) Waksman demonstrates cross-streaking technology to his colleagues.

And Merck faithfully adhered to the terms of the agreement: the company set up production of streptomycin in sufficient quantities for laboratory testing.

Waksman also helped set up production. First, he sent his student Boyd Woodruff, one of the discoverers of streptothricin, to Merck. In his memoir published in 2014, Woodruff writes that, in his opinion, the highest credit (no less than the discovery of streptomycin) deserves the submerged liquid fermentation method, which was brought to technological implementation by Waksman and introduced at Merck.

In general, the method proceeds as follows (antibiotics are still prepared this way). The antibiotic can be isolated directly from the culture in a Petri dish. But very little comes out of it. In submerged fermentation, the bacteria are placed in a bioreactor (a large tank) along with a nutrient medium. The medium is constantly oxygenated and periodically shaken. And the bacteria produce the antibiotic (it is their secondary metabolite).

At a precisely calculated moment, when there is already a lot of antibiotic, but the bacteria are still alive, the antibiotic is isolated, for example, dissolved in a certain organic solvent. And then they crystallize. Each step requires extraordinary precision. When Woodruff joined Merck, he was working on immersion technology for making penicillin. The technology was then tested. And when large quantities of streptomycin were needed, the bioreactors were ready. And Merck, of course, understood what it owed to Waksman and his students.

Using samples provided by Merck, Feldman and Hinshaw began in vivo testing and reported to Waksman two months later that two guinea pigs infected with tubercle bacillus but treated with streptomycin “looked very good”

In 1944, Mayo Clinic staff conducted experiments on tuberculous guinea pigs, varying the dosage of the drug to minimize side effects. Feldman told Waksman in July that “the results look satisfactory,” even though the dose was reduced. The dose reduction that Feldman and Hinshaw achieved was a real breakthrough. Previously, streptomycin had too many side effects and, worse, the tubercle bacillus developed resistance to it. The drug no longer worked.

In September, when a large 60-day in vivo trial was completed, Feldman wrote that “the signs of tuberculosis were absent in almost all cases” In 1945, human clinical trials confirmed the results of the animal tests, and Hinshaw reported in August that thirty-three patients had been treated “and we remain quite optimistic”. And now things were getting very serious.

Entering the market for streptomycin

As a result of the tests, streptomycin was proven to be the first effective chemotherapeutic agent for the treatment of tuberculosis. In addition, it proved effective against a number of other diseases: typhoid fever, cholera, bubonic plague, tularemia, urinary tract infections, etc. As early as 1945, Waksman realized that streptomycin would become an important antibiotic and approached Merck with a request to terminate the 1939 agreement so that other pharmaceutical companies could produce streptomycin and the drug could be brought to market quickly and at a minimal price.

And Merck was generous. The company agreed to assign exclusive patent rights to Rutgers and accept a nonexclusive license to manufacture streptomycin. In addition, Merck demanded and received royalties to offset the funds spent directly on the development of streptomycin. Merck was praised for its generosity, and Rutgers entered into licensing agreements with other pharmaceutical companies.

Because streptomycin could be used against a wide range of diseases, including tuberculosis, it brought enormous profits almost immediately. Initially, the Rutgers Foundation gave Waksman about half of the royalties it received from Merck. When it became clear that this was a lot of money, Waksman reduced his share to one-fifth.

In 1950, Waksman’s share was reduced to 10% (why, we will say later), but since this was still a considerable amount, he ordered that half of it be used to establish the Microbiology Fund.

Dispute over priority

In addition to money, Waksman also received recognition as the “discoverer” of streptomycin. Moreover, he was the sole discoverer. The aforementioned article in Time about Selman Waksman states that it was he who “discovered the wonder drug streptomycin in 1943” (See Note 4). Only Waksman and no one else. On November 7, 1949, Time appeared with a photo of Waksman on the cover. Waksman received awards, honours, and recognition from many, many people.

But in March 1950, Albert Schatz sued Waksman and the Rutgers Foundation. The suit argued that Waksman was not the sole discoverer of streptomycin. The plaintiff demanded an accounting of payments received from licenses granted by Waksman and the Rutgers Foundation to pharmaceutical companies. Schatz also demanded a substantial portion of the royalties he had received up to that point.

Schatz considered himself a co-discoverer of the drug because he was the one who did the main work in the laboratory to isolate it, and because his name was listed first in the original paper on the discovery of the antibiotic (see Note 7) and second in the patent.

In addition, his doctoral dissertation, which he defended in 1945, was devoted to streptomycin.

A rather lengthy process followed, and in December 1950 the case was settled amicably. The president of Rutgers issued a statement in which all parties acknowledged that Schatz was the co-discoverer of streptomycin. Under the agreement, Schatz was to receive 3% of the royalties paid to the Rutgers Foundation. At the same time, Waksman was entitled to 10%, and another 7% was divided among all those involved in the work that led to the development of streptomycin. Although Waksman agreed to the settlement, he always regarded 1950 as the “darkest” year of his life (285). He wrote that he was at the height of his fame and recognition in 1950, but he was depressed that his student, in whom he had invested so much effort and who promised to become a true star of microbiology, treated him so cruelly.

The right of Waksman to be called the creator of streptomycin was not questioned by anyone. But the right of Albert Schatz to be called a co-creator should probably be acknowledged as well. At least this is the conclusion reached by the modern researcher Milton Wainwright in his work9.

Nobel Prize

Streptomycin, of course, was a success of the screening protocols developed by Waksman. Although we can’t forget the very chicken that pecked Streptomyces griseus “out of the earth”. This is precisely the “chance, god is the inventor,” without which there are no great discoveries.

Other antibiotics were also found, in particular neomycin, isolated by Hubert Lechehevalier, which is still used today as an antibacterial agent10.

But it was streptomycin that brought fame and fortune to Waksman and his lab. According to the Rutgers Foundation report, Waksman received $170,000 (after taxes) in royalties, which, adjusted for inflation, would be about ten times as much today. But Waksman donated most of his royalties to the Rutgers Foundation to establish the Microbiology Institute. The Institute officially opened in 1954, and Waksman served as its director for its first four years.

In 1952, Waksman was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his discovery of streptomycin, the first antibiotic effective against tuberculosis”. In his speech at the Nobel Dinner, Waksman said, “With the removal of the danger lurking in infectious diseases and epidemics, society can face a better future, can prepare for a time when other diseases not now subject to therapy will be brought under control. Let us hope that in contributing the antibiotics, the microbes will have done their part to make the world a better place to live in.”

Streptomycin was a major breakthrough, but mankind has not defeated tuberculosis even 70 years later. And it will obviously not succeed in the coming years either.

Waksman retired in 1958. He lectured and traveled extensively. He became a true patriarch of microbiology. A living legend. A benefactor of mankind.

He wrote a biography of the discoverer of cholera and plague vaccines, Waldemar Mordechai Wolff Haffkine. (We plan to cover this outstanding and unfortunately almost forgotten scientist in a series of our essays).

Selman Waksman was surrounded by honor and world fame. His mother would be pleased. He died in 1973 at the age of 85. He is buried in Wood Hole, Massachusetts. On his grave is inscribed in English and Hebrew a phrase from the prophet Isaiah, chapter 45, verse 8: “The earth will open and bring forth salvation”.

Notes

1 All quotations from Selman Waksman, My Life with the Microbes, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1954), are from this edition in the text, with page numbers in parentheses. The book is available online.

2 “An antibiotic is a chemical substance produced by microorganisms that has the ability to inhibit the growth and even kill bacteria and other microorganisms.” What is an antibiotic or an antibiotic substance? Selman A. Waksman. mycology. Vol. 39, no. 5 (Sep. – Oct., 1947), pp. 565-569, p. 568.

3 Waksman S.A.: The Conquest of Tuberculosis. Berkeley, Calif.; University of California Press, 1964, p 117 (reprinted in Ann Internal Med 79:646, 1973). Cited in: Selman A. Waksman, PhD (1888-1973): Pioneer in Development of Antibiotics and Nobel Laureate. B. Lee Ligon-Borden, PhD https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/12748924/

4 Medicine: Man of the Soil. time. Monday, Apr. 04, 1949 https://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0.33009.800002-1.00.html

5 Selman Waksman and H. Boyd Woodruff, “Actinomyces Antibioticus, a New Soil Organism Antagonistic to Pathogenic and Non-Pathogenic Bacteria,”. Journal of Bacteriology, 42 (1941): 231-249.

6 Gram-positive and gram-negative bacteria stain differently for Gram, and this allows them to be classified. Their main difference is that gram-positive bacteria have one thick membrane, while gram-negative bacteria have two thin ones. Penicillin is effective in gram-positive bacteria but not in gram-negative bacteria.

7 Albert Schatz, Elizabeth Bugie, and Selman Waksman, “Streptomycin: A Substance Exhibiting Antibiotic Activity Against Gram-Positive and Gram-Negative Bacteria.” Proceedings of the Society for Experimental and Biological Medicine, 55 (1944): 66-69.

8 Waksman’s correspondence with Feldman and Hinshaw has not been published. It is archived at the Waksman Papers, Rutgers University. Here we cite letters from Selman Waksman and Antibiotics. National Historic Chemical Landmark. Dedicated May 24, 2005, at Rutgers The State University of New Jersey. https://www.acs.org/education/whatischemistry/landmarks/selmanwaksman.html.

9 Streptomycin: discovery and resultant controversy. Milton Wainwright. Department of Molecular Biology and Biotechnology, University of Sheffield England. History and Philosophy of the Life Sciences, Vol. 13, no. 1 (1991), pp. 97-124, p. 124.

10 Selman Waksman and Hubert Lecehevalier. Neomycin, A New Antibiotic Active against Streptomycin Resistant Bacteria, including Tuberculosis Organisms, Science, 109 (March 25, 1949): 305-307.

Vladimir Gubailovskii 12.08.2023