How Russia’s invasion to Ukraine accelerated Europe’s green transition

Machine translation

Despite the energy crisis, the European Union is not abandoning its Green Deal and is stepping up efforts to develop environmentally friendly, cheap and non-dependent on Russian hydrocarbons energy. Russia’s foreign policy has played a significant role in this process.

Gas attack

For several years now, Russia has been using the «gas valve» as an instrument of political pressure. You could say, «a gas war». It started long before February 24. But, while until 2021, Russian gas policy mainly concerned Ukraine, in 2021, many European economists noted some strange declines in gas supplies to EU countries.

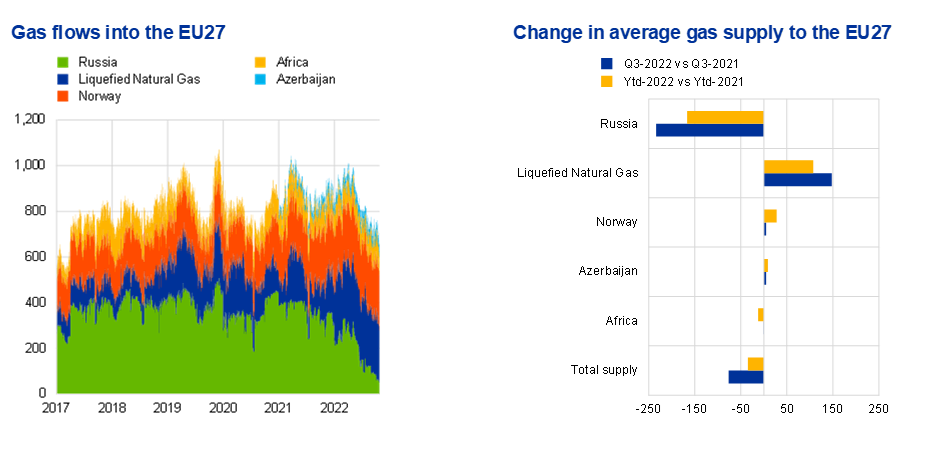

Fabio Panetta, a member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank, says in his speech on European green energy: «There are signs that even before invading Ukraine, Russia manipulated the gas supply to the European market, cutting gas flows and creating scarcity and uncertainty about future supplies. There was already less Russian gas flowing to Europe in 2021 despite higher gas prices and robust demand.»

-

Russian gas supplies to the EU (in millions of cubic meters per day).Sources: Bloomberg and ECB staff calculations.Notes: LNG includes supplies from Russia.The latest observation is for 24 October 2022.

Russia increased gas pressure on the EU even after February 24. Strange «dancing with the valve» around Nord Stream 1 began. First there is a need for a turbine, then no turbine. Without waiting for these «dances» to end, the EU decided to refuse to supply Russian hydrocarbons in order not to finance the war in Ukraine.

The EU economy is heavily dependent on fossil fuels: they account for almost three-quarters of total energy consumption. Most fossil fuels are imported. The EU accounts for 8% of global fossil fuel demand and only 0.5% of global oil production and 1% of global gas production.

It seemed that the rejection of Russian gas should cause, perhaps not panic, but at least discontent in Europe. It did happen, especially in the spring (strikes by drivers and couriers in Britain and Germany, the growing popularity of opponents of the refusal to import oil and gas, such as Marine Le Pen and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban).

But most European countries supported refusing to import hydrocarbons from Russia. And in January, Europeans received electricity bills for 2022. They sighed and paid up. But European governments didn’t resign, and a wave of strikes didn’t follow. Although it was not easy for everyone.

In the fall, the story was popular in Russian social networks that Europeans «wash themselves with a dog» because hot water is prohibitively expensive. But there was no need to «wash themselves with a dog,» and Europe did not freeze out entire cities, as Russian propagandists had prophesied.

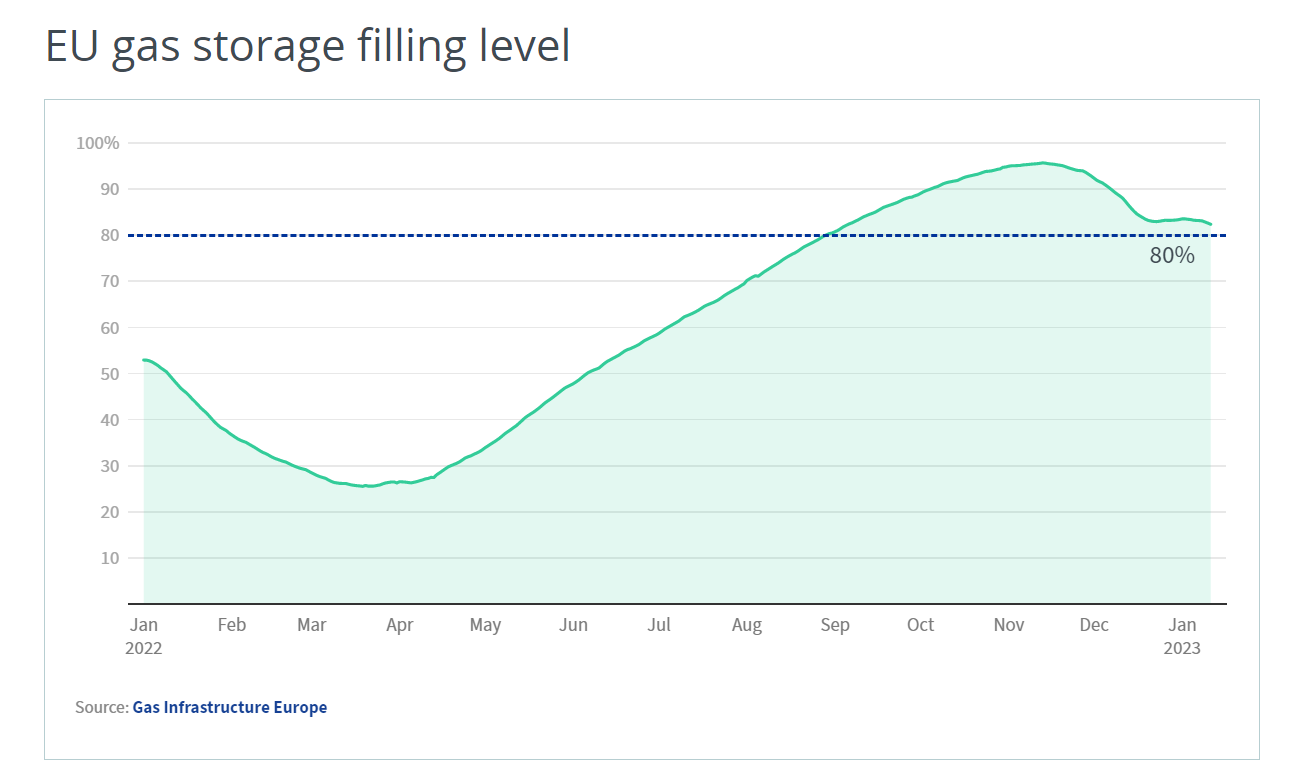

The EU had filled its gas storage facilities to nearly 100% capacity by November (some of the liquefied gas even had to be left for some time in tankers, making them very expensive floating gas storages, it must be said). At the end of January 2023, the gas storage tanks were more than 80% full (in January 2022, only 50% full). There is definitely enough gas until the end of the heating season. And, probably, by April, when usually about 25% of gas reserves remain, this year there will be twice as much.

The Europeans beat back the Russian gas attack. They continue to support Ukraine. We need to be patient for another year. LNG plants in the U.S., which are now rapidly being built, will start supplying in 2024-2025. LNG from Canada and Qatar will come no later than 2026. The fleet is ready.

There will be gas. But there is another way. This is the «green passage,» long declared by Europe. True, one will have to run across it, not walk. And it will be not even a passage, but a steep pass. But according to experts (including Fabio Panetta, whom we quoted), it is possible to cross it.

The Price of Life

When it came to talking about the green transition a year ago, its necessity and even obligation were inevitably associated with global warming. Indeed, global temperatures are rising, CO2 is a greenhouse gas, and the less of it the better. Climate scientists made graphs and predictions (one worse than the other). Scientists would end each presentation or study with the obligatory words, almost like Cato. Except not «Carthage must be destroyed,» but “CO2 emissions must be reduced. Arguments ranged from the reduction of species diversity to the rise of the oceans, mass migration, and starvation. And people, especially the younger generation, felt a responsibility to future generations.

But the challenge Europe faces in 2022 is of a different nature. This is not about saving polar bears. It is literally about the survival of Europe. Not tomorrow, but today. A shortage of hydrocarbons — a shortage of heat and light — is a threat to life. And not the polar bears, but millions and millions of people.

When it comes to survival, all means are good. Isn’t the coal green? Yes, let them, as long as it’s warm. Indeed, coal imports to Europe grew throughout 2022 and rose by 36%. And European countries were actively buying coal from South Africa and Colombia. To put it bluntly, that’s not too close.

Different European countries handled the rejection of Russian hydrocarbons differently: some found it easier, while others found it very difficult. Let’s look at several major European economies.

Poland, one could say, has hardly noticed this refusal. The contract with Gazprom expired in September, and Poland was not going to renew it. Back in 2016, Poland built a stationary terminal to receive LNG and began receiving LNG from Qatar; in the fall of 2022, the country launched the Baltic Pipe gas pipeline carrying Norwegian gas. In addition, Poland is very active in using coal-fired cogeneration plants (almost 80% of its entire energy system is based on hard coal and lignite). And although the country is an importer of coal, it can be bought not only in Russia.

France (Europe’s second economy) has also relatively easily survived the rejection of imports from Russia: 70% of the energy produced in the country is produced in nuclear power plants. France not only provides power for itself, but also supplies it to the European grid: nuclear power usually brings the country more than 3 billion euros a year. Usually, yes, but not in 2022! Just this year saw the shutdown of a number of already aging reactors for scheduled repairs. Because of the incredibly hot summer and drought, many reactors were operating at low load: they became difficult to cool. In September, Nature magazine wrote: «All of this has conspired to force half of France’s nuclear reactors offline for now. This couldn’t have come at a worse time: Europe’s energy prices and supplies are already under immense pressure following the invasion of Ukraine.»

France provided itself with electricity, but could not help its neighbors.

Germany was the hardest hit. Of course, on January 18, 2023, in Davos, Chancellor Olaf Scholz declared that Germany is fully independent of all Russian hydrocarbons. But it came at a high price. The costs of most of the country’s inhabitants have increased by thousands of euros per year.

It is a harsh lesson: Russia cannot be trusted. It is not to be dealt with. But is it only Russia? You can’t do business with Iran either. Maybe Qatar is more reliable?

The rise in hydrocarbon prices has had a quite predictable effect. Producers of renewable electricity began to make super profits. These companies sold their electricity through the common grid. Because the cost of generating electricity at gas-fired power plants rose sharply, the price of electricity on the public grid also jumped. But the cost of renewable energy producers remained the same as it was: neither solar nor wind will become more expensive, no matter what is going on in Russia. Superprofits green companies have become so high that on September 30, the EC has set a limit revenue when selling electricity (180 euros per megawatt-hour). And in Germany, consumers have a chance to reduce their electricity bills by connecting to green companies. Another thing is that not everyone had such a chance.

What if everyone had? If all or almost all electricity was green? At least, like in Austria, where renewable energy accounts for 80%.

The sun, wind, heat from the Earth (we’ll talk about geothermal heat pumps next) are everywhere. So maybe it is safer to use these sources and stay away from unreliable partners trading in hydrocarbons? This is a new twist on the «green transition.» And as it stands, it makes perfect sense to any European, no matter how concerned about global warming.

Bottle Neck

On May 18, the European Commission published a document called REPowerEU: «A plan to rapidly reduce dependence on Russian fossil fuels and fast forward the green transition.»

The European Commission report begins with information about the percentage of the EU population that supports a plan to help Ukraine and move away from Russian hydrocarbons. In May 2022 it was 85% (according to Flash Eurobarimeter survey). At the beginning of January 2023, the level of support has dropped to 74%, but it is still a majority of Europeans. Having secured such strong support, the European Commission sets out its plan for a green transition and rejection of Russian imports.

The first thing the EU insists on in this document is the need to conserve energy. Everywhere it is possible. Specific measures to save energy must be developed by each country.

Щn September 1, Germany adopted the package. It includes reducing the temperature in offices (in particular, the temperature in the corridors — not higher than 19°C), expanding the power of private companies to regulate the temperature in offices and the maximum possible refusal from the street lighting. In August, Berlin’s mayor Franziska Giffi announced that the city planned to reduce energy consumption by 10 percent.

- Or here’s street lighting. In the summer of 2016, when Russian hydrocarbons were flowing quite normally into Europe, the author of this column was in Krakow and watched the European Football Championship final in a cafe on Market Square, in the heart of the city. The square was lit almost exclusively by the lights of the many crowded cafes. There were almost no city lights. St. Mary’s Church went straight into the darkness of night. When we drove into Moscow a few days later, the night city was flooded with light. After the modesty of Krakow, it looked ostentatiously opulent. And there was something barbaric about it. It was embarrassing.

On the podcast Substation (December 2022), Olga Orlova talks to a variety of people about saving energy in Europe this winter. A girl who grew up in America tells how a friend from Germany came to visit her in Chicago. They were wandering around the city and everything was fine until the German girl saw the price of gasoline. She literally got upset: «Gas can’t be that cheap!»

Europeans’ idea of normal lighting or the price of gasoline is pretty hard for someone who grew up in an environment of energy abundance to imagine.

Saving, self-restraint is important, but it’s certainly not everything. The main thing REPowerEU is talking about is precisely the green transition. Before winter broke out, both the authorities and the citizens of Europe were worried about whether there would be enough gas for heating. Today we can already say that there was enough gas. But it wasn’t hot either.

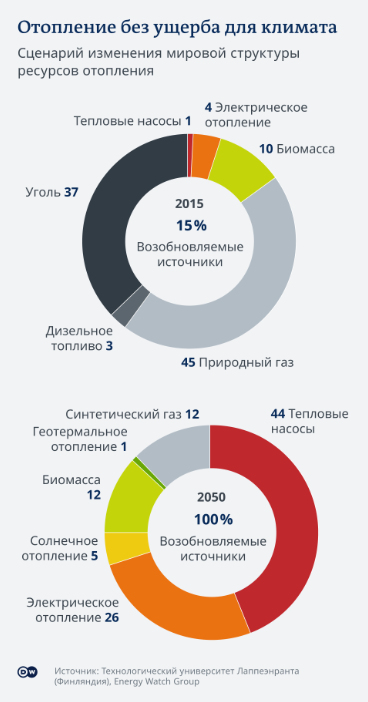

The most energy-consuming form of heat supply to households is central heating. Heat is simply lost in the pipes. And the longer the pipes, the higher the losses. The optimal form of generation and supply of heat in homes available (although not everywhere) today is a ground source heat pumps. This is stated in all EU documents on the green transition.

The idea of a heat pump is quite simple. There is land (or sea, if it is close) at some depth its temperature is about the same at any time of the year. The heat pump is a device like a refrigerator. The refrigerant circulates through the pipes. But it is not warmed by electricity, but by the heat of the earth. When the refrigerant evaporates, the temperature of the environment decreases; when it condenses, it increases. When the house is cold the heat of the earth heats it, when it is hot — cools it. The heat pump coil is buried at a depth where the temperature is stable. The circulating refrigerant carries heat in winter or cold in summer.

Heat pumps today are usually installed in private homes. Installation is quite expensive, tens of thousands of euros, but it is almost a perfect device. Heat is practically not lost, and for the operation of the pump, which delivers the refrigerant through the pipes, you can use, for example, solar panels or wind turbines. There will be practically zero emissions, minimum losses, full controllability of the device by its owner: turn it on, turn it off.

Germany planned to switch to heating 44% of premises with heat pumps by 2050. This is about as much as is currently heated with gas. Now it will have to speed up a lot.

The EU sees the development of heat pumps as a top priority.

REPowerEU envisages very large investments in the green transition. In particular, a lot is said about green hydrogen. Unlike heat pumps, this technology is not yet at the stage where it can be implemented everywhere. In fact, there are only impressive prototypes, for example, for steel mills.

Many experts say that the austerity regime, which the EU is pursuing, will inevitably lead to the withdrawal of most energy-intensive industries from Europe.

For example, Professor Jonathan Stern, who heads the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, told to Al Jazeera: «We are going into a huge recession in Europe. I think it could be worse than [the COVID-19 pandemic recession of] 2020, leading to de-industrialisation, forcing industries to move to the Middle East and the US. None of it is remotely good and it suggests political instability.»

The EC is more optimistic. And green hydrogen is one of the main hopes that the deindustrialization predicted by the expert will not happen.

The report by Fabio Panetta, with which we began our conversation, is called «Greener and cheaper: could the transition away from fossil fuels generate a divine coincidence?» It’s about price stabilization while decarbonizing.

Frans Timmermans, Executive Vice President of the European Green Deal, adds a third component to this «divine coincidence»: «Renewable energy is a triple win for Europeans: it is cheaper to produce, cleaner for our planet, and independent of Russian manipulation.» And today the third is more of a first.

According to a study by E3G and Ember, renewable energy produced 24 percent of all EU energy between March and September. Analysts point to record growth in wind and solar power. It avoided gas costs of 11 billion euros. At the same time, the EU spent about 82 billion euros on fossil gas to produce 20% of its electricity.

However, Panetta believes that with the right investment policy and lowering of bureaucratic barriers — which is already happening and quite dramatically — a «divine coincidence» is quite possible. Solar and wind power have reached a point where the marginal cost of expanding production in these industries is about half that of expanding electricity production from fossil fuels. And investments in green energy are more attractive.

The situation in which Europe finds itself resembles a classic «bottle neck». It is likely that the coming years will see the abandonment of many traditional technological solutions and expensive (in both senses) human habits. And it looks like it will be the energy-efficient, cheap, environmentally friendly technologies and solutions that will survive. Going through a bottle neck is always difficult and even dangerous. In the evolution of the biosphere, a bottle neck is always a transition through which not everyone «squeezes through,» but in which useful mutations take hold. They will determine the future.

- «Enter ye in at the strait gate: for wide is the gate, and broad is the way, that leadeth to destruction, and many there be which go in thereat: because strait is the gate, and narrow is the way, which leadeth unto life, and few there be that find it.» (Matthew 7:13-14)

Text: VLADIMIR MIRNY

Vladimir Mirny 10.03.2023