What can the scientific community oppose to the process of political isolation? What could be the consequences of the break with CERN for Russian high-energy physics? What did Alexei Navalny think about science and education in the Russia of the future? T-invariant’s questions were answered by the co-founders of the free online community “Dissernet” – physicists Andrey Rostovtsevand Andrey Zayakin.

T-invariant: Soon it will be 40 days since the murder of Alexei Navalny. You both took part in developing his political program. What place did science and education occupy in it?

Andrey Zayakin: Alexei Navalny had a photograph hanging in a prominent place in his office in Moscow. A photograph from the Solvay Congress, which depicts Einstein and other great scientists who formed the picture of the world in which we now live. For Alexey, this was not a tribute to fashion, but rather a deep need. He wanted to see those who formed rational ideas about the world. Because it was important for him that in the Russia of the future, reason and common sense would supplant the obscurantism that had been growing over the past years. And it was to reason, to rational approaches, that he appealed when he published his investigations.

But if we talk more specifically about how Alexey saw science and its place in the country, we need to remember those program documents that I was lucky enough to work on with him.

And one of the key points in that program was that scientists themselves should decide what to do. They must be free from that bureaucratic pressure, from the pressure of people, firstly, not related to science, secondly, corrupt, thirdly, sometimes trying to imitate this science.

That is, free from everything that has become signs of scientific management in Putin’s Russia. This freedom of scientific creativity, perhaps, was noted by all the program documents that Navalny and I had the opportunity to work on.

Andrey Zayakin. Photo: “Like this”

T-i: At what stage of Navalny’s political activity did this happen? We are talking about his election campaign for mayor of Moscow in 2013?

AZ: Yes, but not only. Later, in 2019, there was a project called “Plan of Change”, in which, in fact, Alexey’s team presented their vision of Russia’s future.

T-i: Was it Navalny’s own initiative to invite scientists to prepare policy documents?

AZ: Yes. Moreover, I will remind you that when there was no such terrifying pressure as now, Alexey also held public meetings with scientists. Let’s say there was a very famous meeting during his mayoral campaign.

Andrey Rostovtsev:I want to note that Navalny’s election program contained a large number of points, both political and economic, in all fields, including scientific ones. And when we discussed it in Alexey’s office, it was clear that for him all the points were of equal importance, he was well aware of the role of science and education in the development of the country and the formation of society.

And, as Andrei Zayakin correctly noted, Navalny saw the world through the rational glasses of a sound scientific approach. And that is why in economics, in politics, in education, and in science, he denied the place of falsehood and, strictly speaking, distortion of facts.

Therefore, what Dissernet is fighting was important to him. This kind of purity, honesty in relationships in various spheres of life, including science and education, stood on the same shelf with politics, economics, and society in general, which he thought about.

T-i: Did Navalny know the essence and tasks of Dissernet? Did he support this line of activity?

AZ: Alexey, of course, extremely valued Dissernet and believed that this is what we should do in the field of science.

Andrey Rostovtsev. Photo: Vladimir Kudryavtsev’s website

AR: Navalny perfectly understood the goals and methods of work of the Dissernet community. And, moreover, it was clear to him how corruption chains work in science and education. Everything related to the sale and purchase of dissertations, scientific degrees, and diplomas of all kinds – a huge budget is involved in all of this. And here our activities intersected with what Alexey said about corruption, about transferring money abroad or in other areas, with everything he did in investigations. He saw perfectly well that the same thing was happening in science, and, moreover, one of the key ideas that he proposed was that scientists must clean up their own clearing; no one will help them with this. Just as scientists must choose for themselves in a free scientific society what to do, in the same way they must cleanse themselves of the corruption that has grown into science and education over all these years.

Andrey Zayakin and Andrey Rostovtsev together with Alexey and Yulia Navalny. Photo: Yakutia. Info

T-i: In this regard, it seems necessary to continue the conversation about how science and education should be structured in the future Russia. Navalny himself, even in prison, did not stop thinking about its structure. And in order to better understand what changes will be required in the academic sphere, it is necessary to record the problems that it is experiencing today. One of these most important problems is the isolation of Russian science from the West and its turn to the East. Over the two war years, two approaches have emerged in its discussion. The first is that the West has cut off Russian science forever, so we need to turn to the East. And this will ensure Russian science’s survival in new conditions. Russia is a big country: a lot of universities, a lot of talented young people, a lot of academic research institutes. And we must learn to develop independently and cooperate with those countries that are ready to interact with it in the scientific field. This position, for example, was publicly formulated by Alexander Fedorov, rector of the Kant Baltic University, when he said at a meeting with students: “It will never be the same as before”.

And he recommended that students take a closer look, for example, at the science of Uzbekistan. The same idea, according to our information, is heard in informal conversations with scientific administrators: “Now it is difficult to maintain relations with the scientific communities of the West, it is impossible to pay for participation in conferences, it is difficult with visa support, it is impossible to overcome the ban on institutional interaction. But there is China, India, Brazil, Kazakhstan, Turkey, Iran – a huge part of the world that has not turned its back on Russia. And we need to establish scientific and educational ties with these countries.” The second position, which is more difficult to hear publicly, is this: the isolation of Western science for Russia is completely abnormal and unnatural. This is a temporary phenomenon, so we must try to preserve everything we can as much as possible, wait until the war ends, and then relations with the West will quickly be restored. Until this happens, you need to teach students well and try to live until brighter times.

This idea sounds approximately in interview of Fedor Ratnikov, a member of the LHCb collaboration at the Large Hadron Collider at CERN: “The basic idea that all the madness will someday end and normal life will begin again. For this we must prepare students, and we cannot say that that’s it—nothing else will happen with science in Russia—to close our doors and fold our paws.”

What do you think about these two approaches? Which one is the most rational?

AR: I don’t see any contradictions between them. Science is a substance that spreads like water: where there is free space, it will go there. Opportunities have opened up in China to participate in scientific projects – we must take advantage of this. However, now many Russian scientists continue to work in the West and in developed countries. And it cannot be said that all countries where there is highly developed science have stopped working together with the Russians. There is, for example, Germany, where it has indeed become very difficult for Russian scientists to engage in science. And there is, for example, Japan, where it is much easier. And this suggests that it was not scientists who organized the persecution of Russian citizens based on the color of their passport. Rather, some scientists simply succumbed to different political trends, and we see this mosaic. Scientific contacts are now politically charged. But not just paint.

But the second approach is also quite rational, so when the political situation changes, the pressure will immediately disappear and scientists will again be more free in their communication. We remember this from history. German scientists were cut off from the rest of the world during the war years during World War II; they did not publish in international journals, they did not go to international conferences. But the first international conference, to which German scientists were invited, took place in England a year and a half later after the end of the war.

So the boycott of German scientists did not last long, I think that restoration in our field will happen very quickly.

T-i: It is important to note that the first approach is based on the fact that the situation in Russian science and higher education has changed irreversibly. The second is that nothing irreversible happened. In your opinion, have irreversible things happened during these two years?

AR: There are no irreversible things, except death. And even more so in science. Another thing is that there is a delay in science or a lag. Yes, this definitely happened. And a new brain drain has occurred – we have to live with it somehow. But this is not irreversible. I emphasize that in our world science is subject to pressure from politicians: if politics changes, science will change. This just takes time.

AZ: I would like to object to post-war Germany. Yes, people began to come there again for conferences, normal academic life seemed to have returned again, purges were carried out at universities, Heidegger got it, and not only Heidegger, but also many others who collaborated with the Nazis. But at the same time, we note that irreversible changes have occurred with German science: it has ceased to be leading in the world, and the German language has ceased to be the language of science. If we read the early works on quantum mechanics, many of them were written in German. And during World War II, obviously, English became the dominant language in physics, and after that in all other areas, not only in physics.

Russia did not have a dominant position in the world before all this military madness began, but in a number of areas it did have world-class successes. And now, strategically, many of these positions have been lost. And if, after everything returns to normal, extraordinary efforts are not made in terms of financial, in terms of personnel, in terms of institutional, if we finally do not give scientists the freedom to decide for themselves what to do, then, I think, many things will not succeed in over the next fifty to hundred years to beat back. This concerns the point of view of a Russian observer who is interested in science being revived in Russia.

But I want to speculate a little from the point of view of Western policy makers who are now making decisions. And this is precisely the approach of Western politicians, which Andrei Rostovtsev spoke about, because of which passport terror sometimes arises against Russian colleagues in large international collaborations – this is the most stupid thing that Western academic leaders, heads of relevant ministries and foundations involved in financing of science, and those involved in issuing visas to scientists of Russian origin.

What should be the main target function of any reasonable politician from the free world now? Not only to ensure that the war ends, and not only to ensure that the war ends justly, but also to avoid a possible relapse, a possible slide of Russia into a new totalitarianism and into a new branch of military aggression. And in the new post-war Russia of the future, the role of science in preventing this slide will be very important. Because it is precisely this that should provide some protection from a new transition to an irrational picture of the world. And therefore, it is now in the interests of the free world to preserve the potential of Russian scientists, who could then return to their country.

Help:

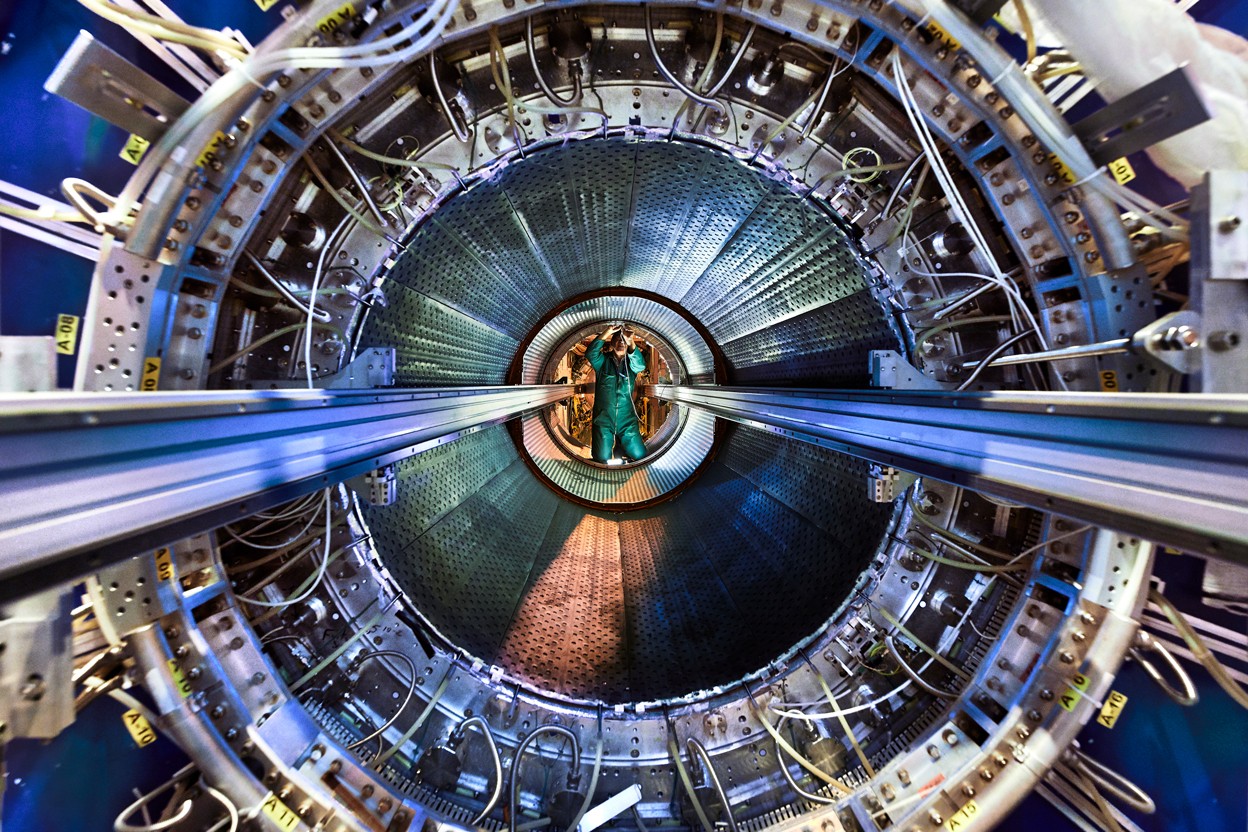

In 2024, the history of cooperation between the Council of the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN) and Russian scientists will end. Since 1993, the status of an observer country has allowed Russian physicists and engineers to participate in the construction of the Large Hadron Collider, become members of large collaborations, conduct experiments, and publish in the best international journals. Since 2012, Russia has sought to become an associate member, but its applications have been rejected for several years in a row. However, scientific ties not only did not weaken, but continued to develop. So, in 2019 CERNand Russia planned experiments on Russian territory.

By 2020, more than a thousand Russian specialists and students were registered at CERN and participated in 22 experiments.

In connection with the outbreak of hostilities in Ukraine, CERN froze the status of Russia, and then announced that in December 2024, when the next five-year term of the cooperation agreement expires, interaction international organization and scientists with Russian affiliation will end.

Several generations of Russian programmers, physicists, mathematicians, and engineers grew up on research and experiments at CERN. Now the war has put an end to the history of the participation of Russian scientists in a unique scientific project that allowed Russian science to remain at the world level.

“After this decision, I felt like a chicken, running around without a head,” commented weight: 400;”>this event is a member of one of the CERN collaborations, Fedor Ratnikov. “I believe that the Russians at CERN will make efforts, but they can be replaced. And when we break ties and say that we will do import substitution, then the West is also doing its own import substitution. Only we need to replace 90%, and they are only 10. I don’t think we will start pulling our detectors out of the installation, I really hope it doesn’t come to that. Although legally I don’t understand very well how this divorce will happen, because it is not spelled out in the collaboration charter,” the scientist points out.

More information about the end of official cooperation between CERN and Russia and ways to preserve the 70-year history of participation of domestic physicists in the work of the Large Hadron Collider – read in our text.

TheLarge Hadron Collider at CERN. Photo: Naked Science

T-i:In connection with the decision of CERN, I again return to the topic of irreversible and irreparable and I want to ask Andrey Rostovtsev. You worked at CERN, this topic is close to you, how do you evaluate this decision?

AR: Yes, indeed, I worked at CERN, but in recent years, for obvious reasons, I have not been involved in this topic. However, I keep in touch with colleagues and follow events. This decision is purely political, and it violates the overall fabric of science. Modern science is not national. When we say “Russian science”, this is not entirely correct: science is integrated into the international community, all connections, contacts are, so to speak, one fabric. And here it’s difficult to distinguish parts of this fabric by the color of the passport: it doesn’t work that way. And the decision that was made at the end of last year at the CERN council is not scientific, it is political. I was not present at this debate, but I heard that it was very heated, and to express all the arguments on both sides, the decision was made by a narrow margin. But at the same time, among the physicists working at CERN, in this entire international company, on the other hand, a kind of counter-behavior is brewing on how to correct this situation.

Firstly, a community arose immediately, which is now called Science for peace, which, so to speak, raises the importance of this question: why this decision is wrong, what needs to be done to correct the consequences of this decision. And these measures, in fact, are being taken, and many institutions are offering Russian scientists to change their affiliation. And someone has already changed it. There is a discussion on the issue of allowing those who are currently writing dissertations on experiments at CERN to complete their PhD work, according to the data. And I tried to find out exactly how many people are now in this tragic situation, when autumn comes and that’s it – will we have to pack our bags? Nobody told me the exact number, but it is about several dozen people at CERN, so there is hope that over the course of this year many of them will solve this problem.

T-i: Is it possible to somehow assess the consequences of the break with CERN for Russian science? Two other experiments remain in Russia, which are intended to be international. One of them is at Sarove, the other – this is NICA in Dubna. Now, obviously, they will be more likely to be more Russian with the participation of scientists from China and other countries, although initially implied a very strong European component. How will the change in the configuration of international cooperation now affect the development of high energy physics?

AR: It seems to me that the most important consequence for the Russian side is that Russian youth do not have the opportunity to learn work in international CERN collaborations. Progress in this area has stopped here, although previously the exchange of youth was very intense.

NICA collider in Dubna. Photo: Moscow Region Today

Laser installation at the Sarov Nuclear Center. Photo: NTA Privolzhye

T-i: According to various sources, approximately 30% of Russian youth have left this field – high-energy physics.

AP: 30% is a dramatic loss. But I believe that there are no irrevocable losses. It is important not to stop progress in this area. Now one of the measures that CERN is planning is to stop Russian scientists’ access to data. If this happens, it will be a serious blow.

AZ:I agree that Russian physics has now suffered quite a big blow, especially to young people. And one cannot fail to mention those who are the most important reason that such decisions are made – these are Russian rectors and directors of institutes who publicly expressed support for the invasion of Ukraine.

Because, unfortunately, these people, whom Dissernet especially loves (rectors are perhaps the most corrupt layer of Russian bureaucracy after State Duma deputies), “ “befriended” Russian scientists with their absolutely disgusting letter in support of military aggression. And it was their letter that directly brought the greatest troubles to Russian institutions.

These rectors never distanced themselves from the positions they held, and this, of course, served as a serious reason for the fact that political decisions were made regarding all Russian scientists.

T-i:This was the meaning of this letter, it was a planned, completely conscious action. We now already know: not all rectors signed it voluntarily; many were under serious pressure and many were blackmailed. And this means that the initiators of this letter well understood the consequences of what would happen. And, as we see, the letter worked. A huge number of international projects were stopped. Do you know any international projects related to Russia that have not been terminated?

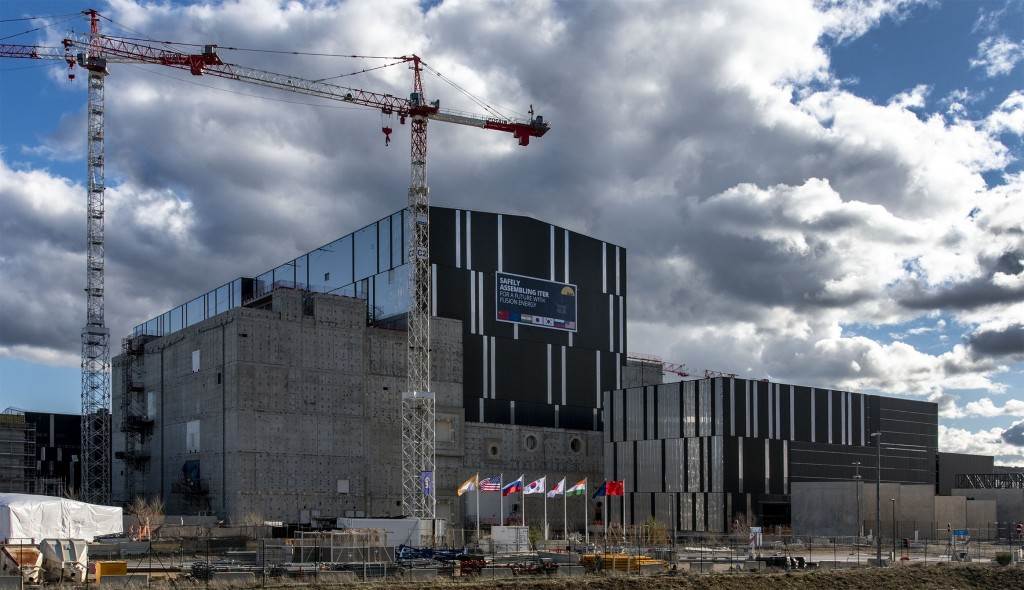

AR: Yes, there are many such projects. Here, for example, is the project Belle is a very large international project in particle physics. It is located in Japan. A strong Russian group is participating in the experiment there, and they have not stopped working with it. Our physicists also work in the project ITER in France. There are a number of other projects in which cooperation continues.

The ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor) building in France. Photo: official website

But I wanted to return to the rectors’ letter. Indeed, not all university leaders signed this appeal—about a third. We know that pressure was exerted, and we also know that some names were entered there automatically. After this there were scandals, and people who were included there without their knowledge tried to jump off this list. Some succeeded, some did not. For example, the rector of the most famous technological university in Russia, Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology, Dmitry Livanorefused to sign this letter. And yet, his university came under the most severe sanctions from the international community and the participants in the experiment. The employees of this university are now being expelled from CERN. This suggests that rational arguments have ceased to work in the scientific community. Although we have before us an example that the rector not only spoke out against this letter, he still had the strength to ensure that his signature was removed from it. And yet, this has had no effect on what politicians abroad think about Russian leaders.

Although the policy of isolationism on the part of the West primarily benefits the totalitarian regime. And ideally, from the aggressor’s point of view, if Russian scientists are placed in this isolation not by his hands and not on his initiative. And the letter – as a provocation – worked successfully in this sense. Why didn’t the West understand this? Mystery. Reason stops working in such a situation for both politicians and scientists.

T-i: There are no signs of the end of the war yet. What, in your opinion, is the likelihood that Western politicians and Western international scientific organizations will rethink their attitude and sanctions policy towards Russian scientists?

AR: I see that these relations are already beginning to be reconsidered. The idea that international ties in science cannot be broken is beginning to dominate in the physics community. The understanding comes that it is not the scientist, strictly speaking, who is fighting. And, well, it is expected that, first of all, the scientific community will accept this idea and promote it. Whether politicians will get involved in this and how quickly this will happen, I cannot say. Well, this is now gaining momentum – yes. The very emergence of initiatives like Science4Peacethe holding of a Forum on this topic indicates that the international scientific community is aware of the impasse politicians are driving them into.

AZ: In order for this to penetrate from the scientific community into political circles, I think it is important to carry out advocacy work with those colleagues who who is now in the West and who can reach out to the leaders of public opinion and the media here. We need to convey to them the simple idea that the fundamental interest of all humanity is now a just world. And the role of science in achieving it, as we have already said, can become one of the decisive ones. It is very important that the West realizes that in the struggle for a just world and for a democratic Russia, scientists with Russian passports should not be victims of this struggle, but its allies.

AR: Returning to the first point of our conversation, I would like to remember that Yulia Navalnaya recently in her program noted that Western countries should not treat Russians are treated as second-class citizens in the West. This also applies to science.

18.03.2024