In the “Creators” project, T-invariant together with RASA (Russian-American Science Association), continues to publish a series of biographical essays about people from the Russian Empire who made significant contributions to world science and technology. Arachnologist and biologist Alexander Petrunkevitch was born in Pliski, in the Chernigov Governorate, but most of his life he worked at Yale University. He became especially famous for his research on arachnids.

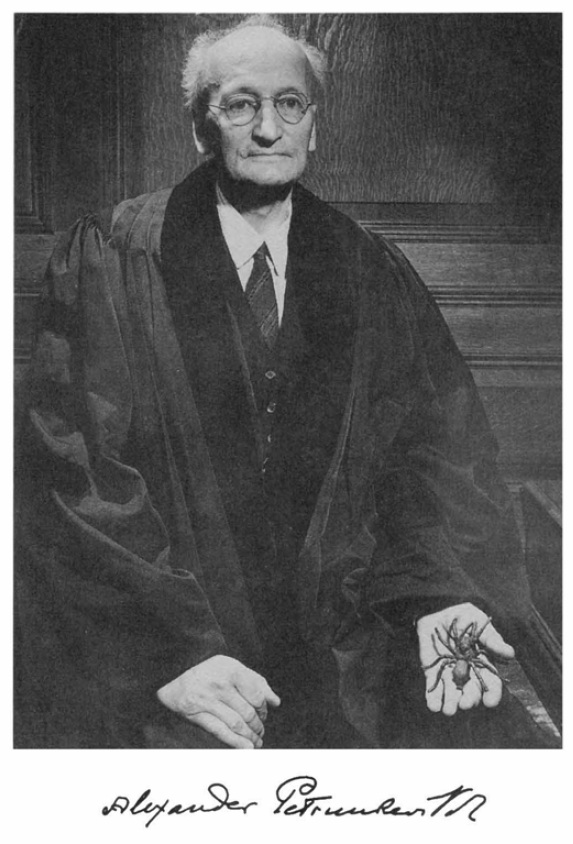

Alexander Ivanovich Petrunkevitch (Courtesy, Yale University Office of Public Information)

“Our entire district represented a piece of that outback that stretched to all ends of Russia and made no exception for the very mother of Russian cities, which was in great desolation.” Alexander Ivanovich Petrunkevitch will write these lines in 1934 – after the revolution, having become a famous scientist. However, he became an emigrant long before the Bolsheviks came to power (however, he also had no sympathy for the new government).

Liberalism is in the blood

The father of the future biologist was Ivan Ilyich Petrunkevitch — a classic Russian liberal of the late 19th century. He was a zemstvo activist from the Chernigov province, advocated for the development of local self-government and the introduction of a constitution. “The struggle between the state and the extreme is entering a new phase and promises to take on a character so merciless that not only the old regime, which has lost all meaning and is unable to even understand the changes taking place in the world, will be under threat, but also our very homeland, which has been steadily getting closer to Western European culture and civilization for two centuries” — he wrote.

Petrunkevitch Sr. sought to unite moderate political forces. He was frightened by the radicalism of the Narodnaya Volya (People’s Will) members, who did not disdain political murders in the name of the high ideals of freedom (and eventually made a successful attempt on the life of Alexander II himself). Ivan Ilyich tried to talk to the Narodnaya Volya members, convincing them to abandon the terror. However, his conciliatory initiatives did not yield results, as did his proposals to the authorities.

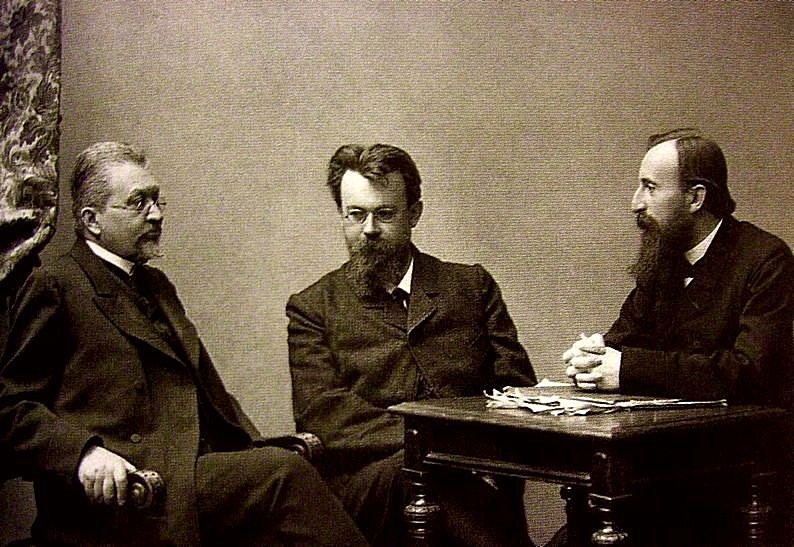

Leaders of the Liberation Union: I. I. Petrunkevitch, V. I. Vernadsky and D. I. Shakhovskoy

Being a member of the zemstvo assembly with the right of decisive vote (voice), one day at a meeting he made a speech about the need for a constitutional system. In it, he condemned the terrorists, but sharply criticized the tsarist authorities. The time for such speeches turned out to be unfortunate: in 1878, liberal reforms had already stalled, and the authorities switched to the fight against radicals. For his speech, Petrunkevitch was exiled to the Perm province for six years under police supervision.

Revolt against repression and emigration

Alexander Ivanovich Petrunkevitch was born on December 12, 1875 in the family estate of Pliski, Bereznyansky district, Chernigov province. Sasha grew up as a versatile boy: he made insect collections (later this would become the main hobby of his life), disassembled and assembled various instruments and engines, studied the structure of steam locomotives and other mechanisms (his friend was the son of Bromley, the founder of one of the largest engineering companies in the Russian Empire).

In 1894, Alexander entered Moscow University and quickly began to make progress in science. He published several articles on the embryology of beetles of the Leaf Beetle family, the physiology of digestion of cockroaches and others. In his free time, he wrote poetry under the pseudonym Alexander Yan-Ruban and translated poetry into English.

After graduating from university, the promising young scientist became an assistant in preparation for a professorship under the supervision of zoologist Alexander Tikhomirov. He worked on silkworms and was known as a retrograde: in his youth he was a follower of Darwin’s ideas, but in his mature years he moved away from them and never missed an opportunity to sarcastically joke about “fashionable” evolutionary theories.

In February-March 1899, the Russian Empire was gripped by student unrest. Protests began at St. Petersburg University: on the occasion of the university’s 80th anniversary, the administration posted an extremely defiant message from the rector, in which he threatened students with arrest and expulsion from the capital for actions discrediting the honour of their alma mater.

A flame quickly flared up from a spark: the rector’s solemn speech on the occasion of the anniversary was booed, and after this the crowd of celebrating students was dispersed by the police, who feared spontaneous riots. The next day, the students, embittered by this treatment, went on strike. The rector responded by calling the police to the university, which only worsened the situation: outrage gripped an even larger part of the students, as well as some liberal-minded teachers.

Soon other universities learned about the strike. An emissary from St. Petersburg student activists arrived in Moscow with an offer to support them. A small organizational meeting took place in the anatomical theater, which became known to the odious “secret police” in charge of political investigation. Rector Dmitry Zernov, who sympathizes with the students, refused to hand over to the police the list of participants in the gathering.

Student demonstration on October 18, 1905

Soon Zernov was removed, and his place was taken by Tikhomirov, who was loyal to the authorities. He immediately began repressions: three students were expelled, three were put in a punishment cell for three days, and four were reprimanded. An attempt to present the rector with a petition asking him to cancel this decision also failed: the meeting was dispersed by the police, and new expulsions followed.

Petrunkevitch, outraged by such actions, wrote a letter to the rector, condemning his inhumane behavior and calling on him to hear the voices of the protesters. After such a speech, the scientist’s career was in jeopardy. Soon, in protest, Alexander Ivanovich left the university and Russia, and settled in Freiburg, Germany.

Nutritious soil for genius

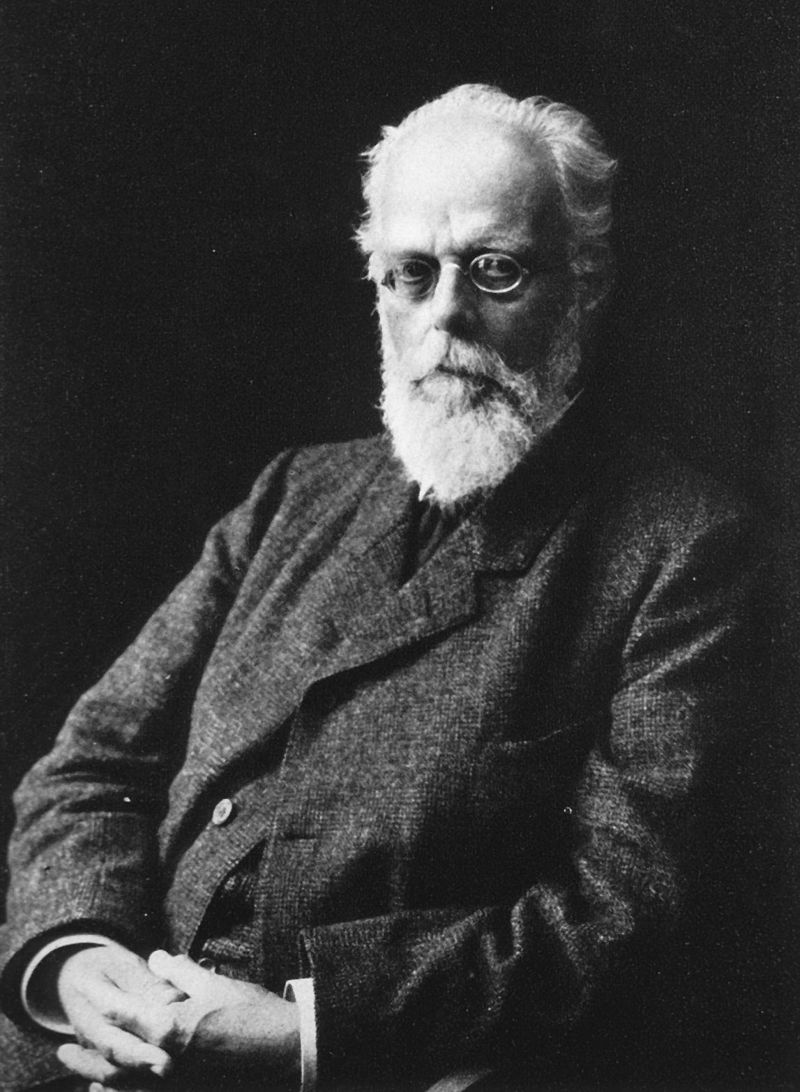

The University of Freiburg, one of the oldest in Germany, was once home to the freethinker and opponent of the Catholic Church, Erasmus of Rotterdam, his associate Balthasar Humbaier and other intellectuals. In addition, there was a strong biological school: one of the professors at that time was August Weismann. His theory about the absence of transmission of acquired characteristics formed the basis of genetics, along with the ideas of Georg Mendel and the American biologist Hans Morgan. Later, Soviet Lysenkoites attacked Weismannism as a reactionary doctrine.

“My first acquaintance with Weismann’s theories was caused by Timiryazev’s fierce attacks on them,” Petrunkevitch recalled. — Under the influence of these attacks, I began to read everything related to the theories of epigenesis and evolution, in the hope of forming my own ideas about the value of Weismann’s theories and the objections raised against them by numerous prominent opponents, including such names as Oscar Hertwig and Gerber Spencer. Gradually, I became imbued with admiration, logic and clarity of Weismann’s constructive mind, the sincerity of his desire to find the right answers to the questions that concern him.”

Petrunkevitch found in Weisman not only a teacher, but also a friend. Warm relations between two scientists from different generations (they were separated by more than 40 years) continued until the end of Weissman’s life. At the suggestion of the professor, Petrunkevitch began to study the cytology and embryology of honey bees. He proved that some bees (drones) are born from unfertilized eggs, that is, through parthenogenesis. In the process, he perfected a method for staining cytological preparations using a phenol-based dye. “Petrunkevitch’s dye” began to be used in many laboratories around the world, since it kept the tissues of preparations soft for a long time.

Petrunkevitch’s successes quickly reached his homeland. “As I heard, they said abroad about Weisman’s three assistants, that one of them sings, the other dances, and the third works. This third was Petrunkevitch,” recalled Moscow University student Efimov. Less than a year later, Alexander Ivanovich prepared a dissertation, which he defended in 1901, and later took the position of a non-tenured teacher (privat assistant professor).

It was difficult to obtain a full-time professorship in Germany. But soon Petrunkevitch’s fate zigzagged again: he met an American woman, Wanda Harshthorn. Soon she became his wife, and the couple moved to New Jersey, Wanda’s homeland. At first it was not possible to find a suitable academic position, and Petrunkevitch used his own money to set up a small laboratory where he continued his research.

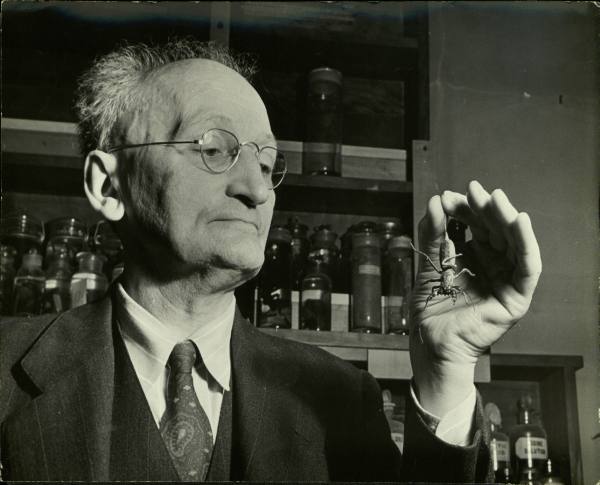

At the same time, he worked as a curator at the Natural History Museum. Studying the museum’s collections, he prepared and published the 790-page “Catalog of Spiders of North, Central and South America with all the adjacent islands, Greenland, Bermuda, the West Indies, Tierra del Fuego, Galapagos, etc.” He later began teaching at Yale University, upon receiving a professorship there in 1917.

For evolution and against revolution

Petrunkevitch was a member of the American Entomological Society and repeatedly spoke at its meetings with reports on the morphology, physiology and taxonomy of arachnids. He was attracted to the systematization of taxonomic groups of arachnids – but not so much for the sake of creating convenient classifications, but for the search for patterns of evolutionary development of different groups of organisms. “Systematics is the mirror of evolution,” he said.

Petrunkevitch greeted the revolution in Russia with a mixture of hope and skepticism. Being a liberal, like his father, he did not trust radical methods of political struggle. On May 1, 1917, he attended a meeting of the New York Economic Club along with politician Elihu Root, a member of the commission sent by the United States to establish diplomatic relations with the Provisional Government. Petrunkevitch warned Root that the position of the new government in Russia was fragile, and it could easily collapse. Root, however, did not listen to the scientist’s words.

After the Bolsheviks seized power, Petrunkevitch criticized Trotsky’s conclusion of a separate peace. In an article for the Washington Post, he stated that Trotsky was bribed by Germany, and such actions lead to a split in the country and civil war. Later, he began to actively help emigrants who fled from Russia: he founded the Federation of Russian Organizations in the USA, and was the rector of the Russian Institute in New York, which provided assistance in training Russian refugees.

Petrunkevitch “was not a one-sided genius” (words from his biography published by Yale University after his death). He published a collection of poems, “Songs of Love and Sorrow,” the first translation into Russian of Byron’s poem “Manfred,” translated English poetry into Russian and Russian poetry into English, and for the centenary of Pushkin’s death, he published prose translations of several of his poems.

Alexander Petrunkevitch with a spider from his collection

Petrunkevitch, known as Pete on the Yale campus, was known as a warm man and a little eccentric—in a good way. In his home he kept an extensive collection of spiders – sometimes there were more than 180 “magnificent” — as he called them — live tarantulas. For some time, in the center of the room there was a cabinet containing the bulk of the British Museum’s unique collection of fossil arachnids, given on loan to him.

In this cluttered, slightly creepy laboratory, Petrunkevitch held weekly tea parties for many years. These meetings were known first as “Pete’s Tea Parties” and, after his retirement in 1944, as “Honorary Pete’s Tea Parties.” Teachers, students and out-of-town guests came to them to talk on a variety of topics and drink strong Russian tea, prepared by Petrunkevitch on a Bunsen burner.

Petrunkevitch died in 1964 at the age of 88. Several species of insects were named in his honor — the Florida freshwater mite Hydrozetes petrunkevitchi, which lives on aquatic plants; the Mexican harvest spider Ruaxphilos petrunkevitchou, the mimrecomorphic (ant-like) spider Micaria petrunkevitchi and the South American shrimp Peisos petrunkevitchi.

Author of the essay Anton SOLDATOV

References:

Obituary of Alexander Petrunkevitch in the New York Times

Petrunkevitch A.I. August Weismann: Personal Reminiscences. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. Vol. 18, No. 1 (January, 1963).

Petrunkevitch A.I. Separate peace means civil war in Russia. Washington post. 1917. Nov 9. P. 3.

Fando R.A. Alexander Ivanovich Petrunkevich – Russian American / R.A. Fando // History of science and Engineering. ‒ 2020. ‒ No. 3. ‒ pp. 40–47.

Petrunkevitch, I. I. From the notes of a public figure: Memoirs / Memoirs. // Archive of the Russian Revolution, published by I. V. Gessen M.: Terra, 1991. – 11. Volumes 21-22. – 1993.

Natural department of the Imperial Moscow University in the 90s of the 19th century: a collection of memoirs. – M.: RUSAINS, 2017.

Petrunkevitch I.I. From the notes of a public figure. Memories. Prague: [B.I.], 1934. – 472 p.

Vasily Nikitin: Testimony in the case of Russian emigration // Diaspora: New materials. – T. 1. Paris; St. Petersburg: Athenaeum-Phoenix, 2001. – pp. 587-591.

Anton Soldatov 18.09.2023