Despite its reputation as a scientific and technological superpower, the Soviet Union missed every phase of the 20th century’s information technology revolution. Although the collapse of the USSR is often explained in purely political and economic terms, in many ways, it was its technological backwardness that bridged the political root causes and its economic decay. Here, we attempt to illustrate this using the example of information technology, which has a technological lag dating back to the 1950s, i.e., the very beginning of the industry.

The revolution

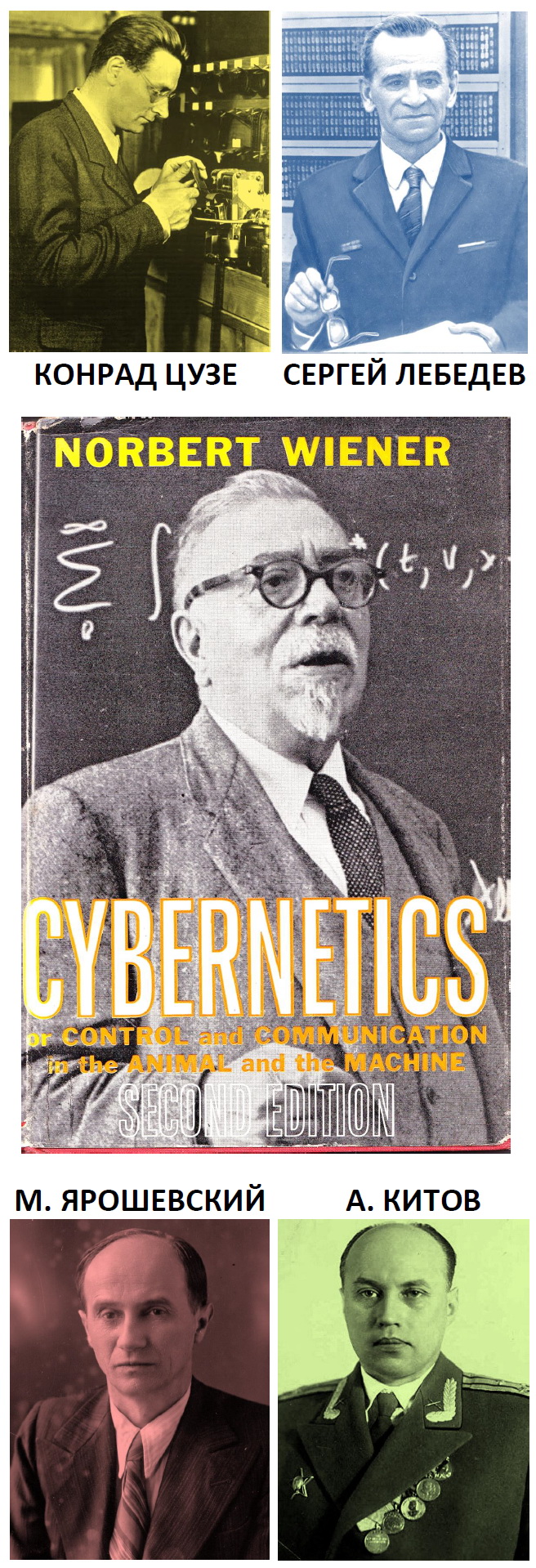

Universal electronic computers are being created in the world since the late 1930s. German engineer Konrad Zuse then took the lead with machines Z1 (1938) and Z3 (1941). Based on electromechanical relays, they were originally developed to meet the calculation needs of military aircraft designers. Toward the end of WWII, Zuse built the Z4, which he miraculously managed to save during the defeat of Germany and leased to the ETH Zurich in 1950.

In the USA, computers first appeared in the 1940s, and they are also used only for specific tasks in radiolocation, astronomy and nuclear weapons research. They were perceived as exotic equipment for special applications. In 1943, Thomas Watson, CEO of IBM, a company that manufactured tabulators (punched-chart data processing devices), said: “I think there is a world market for maybe five computers.”

However, by the early 1950s, things had changed. In 1948, Norbert Wiener published the book Cybernetics, which introduced the new science of control in living and technical systems. The understanding began to emerge that computers could perform much more than just labor-intensive calculations, and could be adapted to all fields of human life. Intelligent machines loomed in the distant, semi-fantastical future.

In 1949, the British company Ferranti launched the world’s first commercial series-production computer, Mark 1. Interestingly, the project brought together Conway Berners-Lee, one of the computer developers, and Mary Woods, a programmer whose son Tim Berners-Lee later created the World Wide Web. UNIVAC I, the first universal commercial computer in the United States, was launched in 1951. During the 1952 presidential elections, it was used to predict the outcome. In 8 years, 46 machines of this type were built. Computer began to revolutionize the world.

The Soviet Union had no time for computer technology during wartime. In 1948, however, work on the development of Soviet computers was begun at the global level and at several centers at concurrently. Among these centers was the Special Design Bureau No. 245 (SKB-245), established in Moscow by the USSR Council of Ministers. Also, worth mentioning is the group of Acad. Sergei Lebedev in Kiev, which created the first purely electronic computer in continental Europe (MESM, 1950). Within a few years, the USSR already had a number of its own first generation (i.e. tube based) computers. Some of them were serially produced and used for scientific, industrial and military purposes.

A small delay at the start appears to have been neutralized, and the country has all chances of gaining ground among the leaders of the computer race. In spite of the recognized usefulness of computer technology, cybernetics ideas were not accepted in the USSR. They are seen as a claim by “technicians” to directly participate in public administration, and thus as an ideological threat to the Communist Party’s monopoly. Additionally, some of Wiener’s ideas seemed anti-Marxist. For example, his claim that information to be neither matter nor energy, but rather an independent entity, appeared to be contrary to the Soviet mandatory materialistic ideology.

Discrediting

We need to make a small digression here. Everyone knows that genetics and cybernetics were declared “bourgeois pseudosciences” in the late Stalinist Soviet Union. However, this happened to them in very different ways. The “pseudoscientific” status of genetics was the result of an intra-academic struggle for influence. Lysenko’s supporters made unrealistic promises to Soviet officials and eliminated scientific rivals, whilst hiding behind ideological rhetoric.

There was no such scientific split in cybernetics. In a sense, cybernetics was was persucuted from outside due to misunderstanding. As the Cold War intensified, workers on the ideological front were compelled to increase their criticism of bourgeois society. And just around this time, the Wiener idea of cybernetics began gaining a lot of attention. A military orientation of most then-current computer developments, coupled with the philosophical motivations of cybernetics, made the latter an easy target.

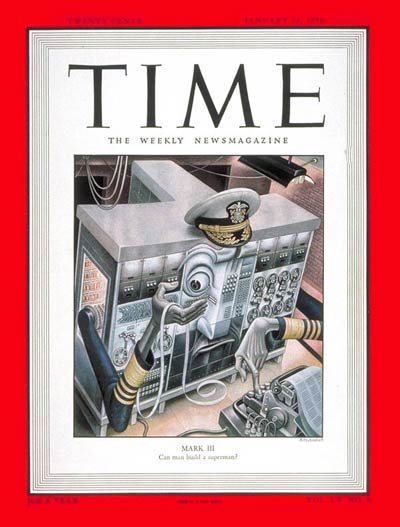

In 1950, the Soviet journalist, writer, and propagandist Boris Agapov published a lengthy scolding article in Literaturnaya Gazeta, where he was working as science editor, about capitalists who would make robots to get rid of workers and mechanical soldiers to oppress those workers even more. Agapov does not mention the word “cybernetics” and admits that he knows “no details” about Norbert Wiener, but accuses him of narrow-mindedness and even aggression. This conclusion was apparently derived from some quotes Wiener gave in a Time magazine article, which featured the newest American computer Harvard Mark III in an admiral’s uniform on the cover, since it was intended for the Navy.

By the way, some theses outlined in that Time article seem even more relevant and persuasive today than they did back then. Here are some quotes:

- «“The second industrial revolution,” … will devalue the human brain as the first industrial revolution devalued the human arm,» according to Norbert Wiener.

- «What Is Thinking? Do computers think? Some experts say yes, some say no. Both sides are vehement; but all agree that the answer to the question depends on what you mean by thinking.»

- «When a machine is acting badly, we consider it a responsible person and blame it for its stupidity. When it’s doing fine, we say it is a tool that we clever humans built,» in reference to the lab of Prof. Howard Aiken, designer of Mark III.

In 1952, psychologist Mikhail Yaroshevsky developed the subject further in Literaturnaya Gazeta. His article appeared under the title “Cybernetics — the ‘science’ of obscurantists” was his article and was written in the denunciatory style that was typical of Stalin-era publications. The article was placed on the last page of the paper, and the names of the editorial board members can be seen below it. Among them were editor-in-chief Konstantin Simonov, author of the famous “Kill Him!” poem which served as a concentrate of wartime hatred, the already mentioned Boris Agapov, and, for example, the writer, academician, and Chairman of the Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Ukraine Alexander Korneichuk, a five-time winner of the Stalin Prize and later six-time recipient of the Order of Lenin (the highest Soviet state award).

Live with wolves, howl like wolves

Unlike Boris Agapov, Mikhail Yaroshevsky was a serious scholar and taught a course on the history of psychology at Moscow State University. Yet he had suffered political repression while a student. Then in 1938, he was arrested on trumped-up charges of membership in a terrorist organization and was forced under torture to sign a false confession: that he has planned to blow up the Palace Bridge in Leningrad during the May Day demonstration and kill Andrey Zhdanov, head of the Leningrad Regional Committee of the Communist Party. The sentence was 10 years in a camp. But shortly thereafter, People’s Commissar Nikolai Yezhov, the organizer of Stalin’s mass repressions, was fired, and all those convicted on the case were amnestied. Yet the criminal case was not closed, and it hung over Yaroshevsky until 1991.

One could assume Yaroshevsky probably paid for his freedom by writing a propaganda article against cybernetics. However, his disciple, Arthur Petrovsky, quotes the words in his book Psychology and Time, which demonstrate that it was written quite sincerely. Moreover, Yaroshevsky was not inclined to enter into such deals with the authorities at all. During the campaign against “cosmopolitanism,” he was required to snitch on his teacher Sergei Rubinstein, to avoid this, he abandoned Moscow State University and the Institute of Philosophy and in two days left for Tajikistan, where he worked for 15 years in provincial pedagogical institutes.

The most likely explanation is Yaroshevsky believed what he was writing, and indeed thought that American scientists were inventing nonsense that was obvious to any schoolboy or newspaper reader. It is possible the professional bias affected this, as he would never compare a piece of metal to a human being. In addition, his views were influenced by Soviet ideology, which celebrated the will of man and people — after all, one cannot assume that it would be replaced by controlling cybernetic brain.

A scolding tone of the article reflects the mores of the era. In public speeches, ideological doubts and objections were easily, and even with necessity, elevated to angry attacks and political accusations. Even a man who himself faced a bogus criminal investigation used all the same aggressive rhetoric as his persecutors.

Following the writings by Agapov and Yaroshevsky, cybernetics was trashed in publications ranging from popular science magazines to the Philosophical Dictionary. Strange as it may seem, they did not affect specific technical developments, but they did slow down attempts to envision the future of computer technology in depth.

Rehabilitation

Specialists instantly realized the attacks on cybernetics were unfounded, but it took considerable effort of scientists to remove its stigma of pseudoscience. In 1952, the military engineer Anatoly Kitov defended the first thesis on programming in the Soviet Union, dealing with ballistic missiles control. The same year, given permission to read Wiener’s “Cybernetics” in the SKB-245 closed repository, Kitov was convinced it was not pseudoscience and wrote a detailed article “The main features of cybernetics”, in which he retold Wiener’s ideas and criticized the pseudoscience accusations. The article was published, however, only three years later, when such a heavyweight like Acad. Sergei Sobolev (deputy to Acad. Igor Kurchatov, head of the Soviet atomic project), who supervised the calculations of radioactive isotope enrichment, joined as a co-author.

Cybernetics was rehabilitating in 1955, when the article was published in the journal Voprosy Filosofii" content="Problems of Philosophy, one of the main ideological periodicals of the Communist Party. A further three years later, Wiener’s book “Cybernetics” was finally translated and published in Russian — 10 years after the original.

Together with the country, Mikhail Yaroshevsky reconsidered his views on the new science. But his next article in the same Literaturnaya Gazeta, almost led to another criminal case — for divulging state secrets. A military prosecutor clung to the phrase describing Soviet computing machines as superior to American ones. After being dragged from Tajikistan to Moscow, the author explained that he wrote so out of Soviet patriotism, unaware of any specific developments, and he was strictly advised to find other ways to express it. As a side note, the traditional closed nature of Soviet technological developments also hindered the country’s leadership position, since it prevented competition and ideas exchange.

Due to these politically provoked ideological misunderstandings, the development of Soviet computer technology in the initial period was mainly carried out by engineers and applied scientists during the initial period. Though they were good at solving technical problems, they lacked a comprehensive view of the new industry’s development. Even if there were people in the country capable of embracing this perspective, they were not exposed to full of full-fledged scientific communication, and their ideas were not critically evaluated. So began the Soviet lag in information technology development.

As a result, cybernetic euphoria did not emerge in the Soviet Union until the 1960s, after it had already mostly subsided in the West. Due to the delay of the first computer revolution, the next, much more important and practical stage of the computing technology development was not realized in time. It is the evolution of software development into a standalone industry. But that is another story, which we will discuss next time.

Text: ALEXANDER SERGEEV

P.S. Here are some portraits. Above: Konrad Zuse and Sergey Lebedev — pioneers of the computer era, who worked in totalitarian states and used to sweep away any obstacles on their quest to perfection. Below: Mikhail Yaroshevsky and Anatoly Kitov — two individuals with strong convictions and a sizzling glance. Through the efforts of one, cybernetics in the USSR was discredited, and through the efforts of the other, it was rehabilitated. In the middle: Norbert Wiener, who predicted the future of information technology until the next century, despite the lack of piercing eyes, but his ideas were described in 1952 by Literaturnaya Gazeta as follows:

In its convulsive attempts to realize its aggressive plans, American imperialism throws everything at risk — bombs, plague fleas, and philosophical ignoramuses. By the efforts of the latter, cybernetics was concocted, a fake theory that is utterly hostile to humanity and science.

Alexander Sergeev 26.04.2023