How Russian mathematics lost to the war

Is there any chance, in the conditions of external isolation, to preserve a living system of mathematical knowledge in Russia through international solidarity, personal connections, and secret online teaching? This question now concerns those who have left and those who have stayed behind.

Lost championship

In July 2022, one of the most important events in world science was to be held in St. Petersburg: the International Congress of Mathematics. Traditionally, it has been held every four years since the end of the 19th century. The main mathematical awards of the world are presented there. Winning the right to host the congress is as honorable as the right to host the Olympic Games or the FIFA World Cup. This is exactly the scheme that Russia used when it fought for the right to host the congress. It had only happened once before, in 1966, when Moscow was one of the world capitals of mathematics.

In 2018, the Russian government’s bid to host the congress was overseen by Arkady Dvorkovich. Russian mathematics was represented by two Fields laureates: Andrei Okunkov and Stanislav Smirnov, both of whom had worked abroad for a long time, but had closely cooperated with Russian universities. This tactics succeeded — St. Petersburg won the bid against Paris. And then work of the organizing committee began. A special series of satellite conferences in various Russian and European cities was planned, films were made about the Congress, books were prepared for printing, and work began on arranging special visas for mathematicians, similar to visas for soccer fans. However, the efforts of hundreds of remarkable scientists were in vain: a week after the beginning of the war, the International Mathematical Union announced that it did not consider it possible to hold the congress in Russia. As a result, for the first time in the centennial history of the congress, the scientific sessions with reports were held online, and the Fields Medal award ceremony was moved to Helsinki.

«The Nobel Prize in Mathematics,» as the Fields Prize is often called, went to the Frenchman Hugo Duminil-Copin, the Briton James Maynard, the Korean-born June Huh working in the United States, and the Ukrainian-born Marina Vyazovskaya working in Switzerland. During the Fields Medal ceremony, Vyazovskaya was speaking in her speech about the Russian invasion of Ukraine. She gave the cash equivalent of the award to help her homeland.

There, in Helsinki, the award for popularization of science, the Lilavati Prize, was presented to Nikolai Andreev, head of the Laboratory for Popularization and Propaganda of Mathematics at the Steklov Mathematical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (MIAN).

Within Russia throughout the country, most of the mathematical conferences timed to the congress did not take place. A number of scientists who participated in the preparation of the congress left the country. Andrei Okunkov terminated his academic leadership of the International Laboratory of Representation Theory and Mathematical Physics at the Higher School of Economics (HSE). His personal page on the university website is now deleted. Together with eight thousand scientists from Russia, he signed the «Open Letter of Russian Scientists and Scientific Journalists against the War with Ukraine».

Stanislav Smirnov remains a research supervisor at the Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science in St. Petersburg State University, but most of his time, according to his colleagues, is spent in Switzerland at his main place of work.

Petersburg. Disrupted mycelium

By 2022 a mathematical ecosystem necessary for the healthy growth of science had formed in St. Petersburg. The St. Petersburg branch of the Steklov Mathematical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (POMI) was highly active; the best scientists were engaged in cutting-edge research here. The new Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science at St. Petersburg State University was gaining popularity and attracted the best students, including participants of International Mathematical Olympiads. On the base of the faculty and the academic institute, the Leonhard Euler St. Petersburg International Mathematical Institute was revived, and in 2020 it received the official status of a world-class mathematical centre. The centre was supposed to become a point of academic mobility, the Russian analogue of the Oberwolfach mathematical center, where scientists from different countries came for temporary positions to participate in conferences and seminars. The money allocated for its creation was unbelievable by the standards of mathematical science — more than a billion and a half rubles ($20m).

«On February 24, it became clear: what we have been doing for the last twenty years is broken, — says mathematician Andrey P. (name changed) from St. Petersburg. — We had been restoring mathematics after the poverty of the 1990s, we were fighting for young people, for meaningful projects, for money so that we could enter the international market with them and attract foreign scientists to St. Petersburg. And we managed to do this. Postdocs from France, Canada, and America came to us. We had a lively academic atmosphere. We were preparing for the Congress, there were many other activities associated with it, an extensive programme of conferences, and young people were actively engaged in the history of science. After all, we have the archives of Euler, Kepler. And we began to prepare publications representing the tradition of mathematics in St. Petersburg from the 18th century to the present day.»

For now, almost all conferences at the Euler Institute have been canceled. Some still want to come, but technically it is now so challenging that few are willing to overcome the difficulties of travelling. And for some, it has become completely prohibited. So in the summer of 2022 there was a conference on mathematical hydrodynamics, dedicated to the 100th anniversary of Olga Ladyzhenskaya. There is a scientific school associated with her in Sweden, so the Swedes really wanted to come to St. Petersburg, but they had an administrative ban on going to Russia. Also the Euler Institute lost funding from a large private Simons Foundation.

The abrupt cutoff of international contacts sent a clear signal to active researchers, whose scientific life is impossible in isolation. During the last war year about half of the professors of the Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science at St. Petersburg State University, founded at the initiative of Stanislav Smirnov with the support of Gazprom, Yandex, and other large companies, left Russia. Neither in the fall of 2022, nor in January 2023, did the State Duma Defense Committee support the initiative to defer mobilization for scientists.

«A courier in an expensive car brought me a huge bouquet in the form of a Voronoi diagram»

Olga (name changed) got her PhD at a Swiss university, after that she worked as a postdoc in Belgium. In 2018 she returned to Russia, as she got a place at the newly created by Stanislav Smirnov Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Sciences at St. Petersburg University. She passed the competition for the position of senior lecturer and then associate professor with a contract until 2025. She also used to work at the Euler International Institute and participated in the Congress preparations. Today she is in Switzerland again, but this time as a participant of the Scholars at Risk program.

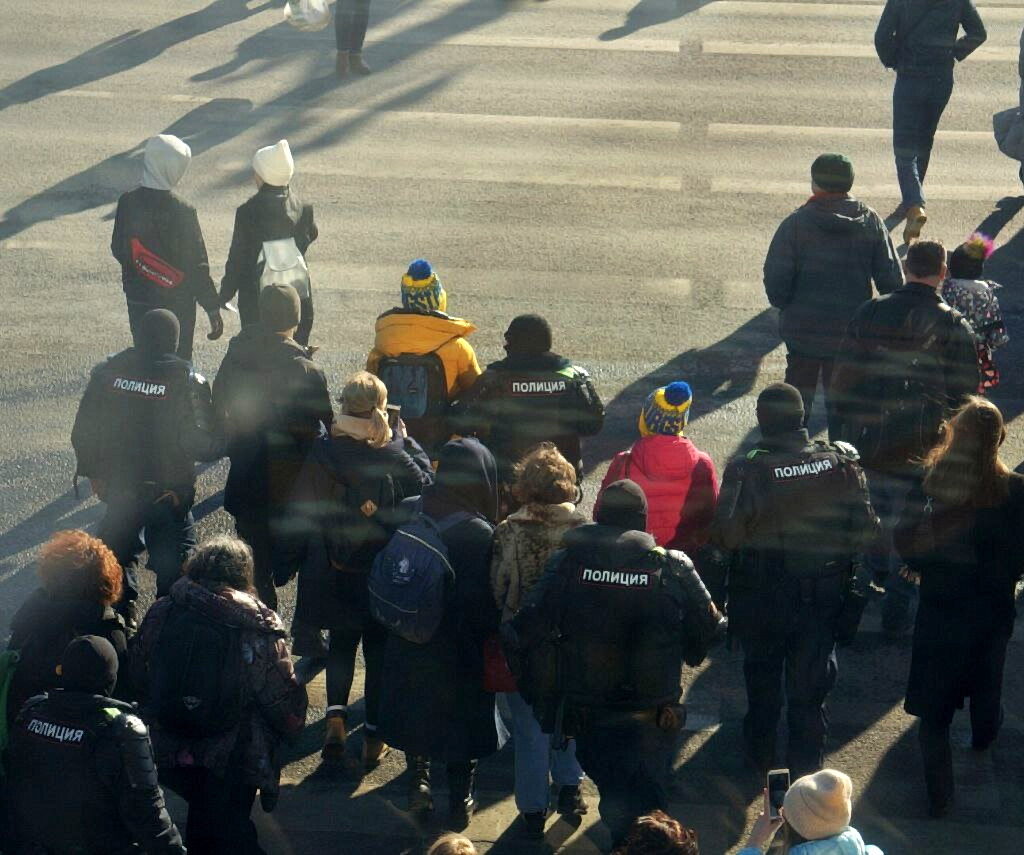

«From the first days of the war there was a state of nightmare. It was my birthday at the beginning of March, but I couldn’t celebrate and just cried all day. My good friend and former colleague from Europe told me to leave and not go to protests. His genetic memory (and he was Jewish) told him that those survived who hid and fled, not those who openly opposed the regime. Nevertheless, I decided to go to the anti-war rally the next day. By the time the meeting began, Gostiny Dvor was already cordoned off by the OMON. If anyone stopped, even for a minute, he was immediately detained. In front of me a man pulled out an Ukrainian flag, and I started to count: they detained him in ten seconds. In the crowd I met a woman who had relatives in Ukraine. She couldn’t believe it when she heard them talking about the bombing and killing, and it wasn’t until just before the day of the rally that she realized that the war was real. She was in shock, and I wanted to support her. In the pedway we bought yellow and blue hats — we just had to express our attitude toward what was going on. We weren’t wearing these hats for long — police caught us right on the Kazansky Bridge.»

Olga spent the night at the police station. The policewoman at the station did not respond to the fact that Olga had children and under the law a woman cannot be detained for more than three hours. My advocate was told, «If she has no one to leave the children with, we’ll call a patrol, take the children away, and give them to the child protection services.» The next day she was taken directly to court from the police station. They found her guilty, fined her and let her go home. «And at this point I finally matured the decision to leave Russia. I posted pictures of my detention on Facebook and wrote that I was looking for a job abroad.»

Detention of Olga N. at an anti-war rally

Almost immediately, a Ukrainian colleague from her last job responded. Although he now communicates with Olga only in English, it was he him helped her apply for the Scholars at Risk program in order to go to Switzerland. Before returning to St. Petersburg, Olga was not at all interested in politics. Her formation as a scientist took place in Europe, where she was busy with her children and science and did not follow the news.

«My mother was wary of my idea to return to Russia, she tried to explain something, but her arguments did not seem significant to me. In Switzerland, I heard that something had happened to Crimea, and I was also surprised that the guys from Ukraine, with whom I studied, suddenly switched to Ukrainian with me. But I didn’t pay much attention to this. And when I came to Petersburg, I quickly realized that it was hard not to think about politics here. Too many things point it out to you. Work and administrative processes are crooked, everyone breaks the rules, you can’t do anything by law, and it’s scary to bypass the law. And soon, in our university, Associate Professor Sokolov killed and dismembered a graduate student, who also happened to be his lover. And I had a nervous breakdown back then. It was impossible to accept the fact that this deranged man openly lived with his graduate student, behaved inadequately, all saw and knew it, but no one even tried to prevent the tragedy. This seemingly internal university story affected me a lot. And when Navalny was poisoned, I developed a final and definite attitude toward the Russian state as a machine that destroys people».

At the time, Olga was a member of the Coordinating Council of Young Scientists under the President of the Russian Federation. The administration of the faculty asked her to join the council, in an effort to help get some help for the congress in particular.

«I agreed, not really understanding what I was getting into and what kind of organization it was. Imagine, a special man in uniform came to our university and personally brought a letter from the Administration of the President with a request to send me to Moscow to meet with the leaders of the Council. So they had money for this man with shoulder boards, but they had no money for my ticket to Moscow. I was summoned to Staraya Square [where the Administration of the President of Russia is located. — T-i] and asked what my goals were. It was the wildest conversation I ever had. I started telling them something about mathematical problems, about how I wanted to create my own research group. They grinned: “We do not really like your answer. On the contrary, the girl before you, she wants to win the Nobel Prize, that’s a real ambition. And they made no secret of the fact that the Coordinating Council was free labor power for them. It was, we did do some technical work, for example, the calculation of scientometric indicators in the processing of applications for a government prize. They needed our work for free, even though they had money for incredible things. Once, for example, for my birthday they brought me in an expensive car a huge bouquet in the form of a Voronoi diagram. However, I didn’t participate in most of the Council’s events and I didn’t go to meetings in different regions, either. Once in a general chat room, Council members joked that if we hold a meeting in the Crimea, we will know who is ours and who is not ours.»

Olga was expelled from the Council in August 2020 right after she expressed her opinion about what happened to Navalny in social networks. She was not warned about anything, they just sent her a copy of the rotation order signed by A.A. Fursenko [Assistant to the President of Russia, former Minister of Education and Science. — T-i]. Olga continued to teach at the university and help prepare for the Congress, until the February 20 meeting of the Security Council of Russia, after which she received clear signals from her foreign colleagues that there would be problems with the Congress in Russia. On February 24, the mathematicians in St. Petersburg realized that it was not just Congress that was cancelled.

Members of the faculty administration had different approaches to the situation: some clearly and loudly expressed their negative attitude toward the aggression, while others sternly warned that the faculty was out of politics and that no statements could be made on behalf of the staff. Nevertheless, an open letter from employees of the entire St. Petersburg State University in support of the war in Ukraine soon appeared, signed, among others, by one of the faculty members.

There were even ideas of organizing a mathematics department in exile. But it was hard to find out how many staff members were really willing to participate: it seemed that no more than half. So they left, whoever they could, with the help of recommendations, which were written, in part, by the faculty leaders. Far fewer students left than faculty members. No more than a quarter.

«First of all, it’s harder for them to get off right away; you usually have to apply in advance for academic programmes, explains Olga. — And secondly, we had very spoiled students, these are the Olympiad students, they were told from childhood that they were the smartest, provided with excellent conditions. I found for one graduate student the possibility of visa support to Belgium, but he said to me: “Why would I want to do that? I’m attached to my homeland. And why is Europe telling us how to live?” He wasn’t ready to go to war, though, and decided to hide from mobilization inside the country if necessary.»

As at the faculty, at the Euler International Institute the administration objected to an anti-war statement on behalf of the organization, arguing that it would mean the immediate dissolution of the staff. Preserving the international center in the form in which it was designed was unlikely to be achieved through silence. Under conditions of isolation from European, American, and Canadian universities, it is impossible to realize the idea of an international mathematical hub, where advanced knowledge is accumulated. But the money for its realization remains.

And this situation is exactly the opposite of the situation in the 1990s, when scientists were leaving poverty for stable positions in European, American, and Canadian universities. Today, on the contrary, many of those who got into short-term temporary positions abroad have lost status and money. Except for those who accepted invitations from China, the Arab Emirates, Pakistan, India, and Brazil. One mathematician, who wanted to remain anonymous, received from the UAE a luxurious offer of a contract comparable to that of a soccer player in terms of conditions and salary. He declined.

«First of all, I’m too old to change my whole life. I have a very strong attachment to St. Petersburg. We have wonderful students, so who am I going to leave them for? I am convinced that the war will pass, but mathematics in Russia must survive. And someone has to stay in the shop,» — as Ludwig Faddeev said in the 1990s, when ‘maths Petersburg’ was half-empty.»

Indeed, since the early 1990s, more than forty people left the St. Petersburg branch of the Steklov Mathematical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (then LOMI) out of one hundred unique specialists in all fields of mathematics. Academic Ludwig Faddeev was one of the main custodians of this «shop» and participated in its revival as much as he could, right up to skiing with Putin, to lobby for mathematics, to maintain its prestige, and to explain to the authorities the need for its development. He lived to see the moment when, through his efforts and the efforts of dozens of colleagues, St. Petersburg once again became the world center of mathematics. Ludwig Faddeev passed away in 2017, without seeing forty people leave his beloved POMI again in just six months in 2022. In the 1990s, «sitting in the shop,» surviving mathematicians waited for money and young people. And what can they wait for now?

«We now, unlike in the 90s, have a lot of money and many brilliant students, — the scientist continues. — But they have closed the door to big international science for us. However, Russian scientists are used to this. In the gloomy 1920s and 30s, Russia had the highest mathematics. One of the greatest conferences on algebraic topology was held in Moscow in the terrible year of 1935. Kolmogorov and Alexandrov made two powerful talk there. During the same years in Leningrad, Yakov Perelman wrote his popular books on mathematics. Mathematics in Russia has seen a lot and will survive this as well. But we actively write recommendations to anyone who wants to leave. We find both students and associate professors. China is a particularly popular destination.»

In the very first months of the full-scale war, at the initiative of one of the most influential Chinese-American mathematicians, Yau, invitations were sent to dozens of young and mature Russian scientists from Chinese universities with lucrative long-term contracts. The Chinese paid for good housing and offered money that exceeded the average American university salary. Many took advantage of this offer.

«It was unbearable to see it»

Nikita Kalinin grew up in St. Petersburg, wrote his PhD thesis in Geneva, then worked in Mexico. In 2017 he decided to return to St. Petersburg, wanting to get into the same new faculty of mathematics. But due to the high competition, Kalinin was not able to get a job right away, and he got a job at the Game Theory Laboratory of the St. Petersburg branch of the HSE. Two years later Kalinin was hired at St. Petersburg State University.

«Mathematics was developing very dynamically in St. Petersburg at that time. Professionally, I was absolutely satisfied. I love to work with students, and our students were just incredibly smart.»

At the beginning of the war, Kalinin was working simultaneously at two universities and was preparing a book on the history of mathematics in St. Petersburg, timed to the Congress. The book should introduce the brightest names who worked in St. Petersburg from the time of the Bernoulli brothers and Leonhard Euler to the present day. The book has not yet been published. But if anyone decides to continue this chronicle in the future, the year 2022 will go into it as the year of great losses.

«“In the first days of the war there was a surreal feeling, as if I had been caught up in a bad movie. I still have it, though. I felt that my head had been cut off. It was immediately clear that this was the end of everything. Everything normal. And that it would last for a long time, for ten or twenty years. My wife and I made the decision to leave at once: it was unbearable to see it. I was haunted by the biblical image of a herd of pigs running to the lake to drown. And the only thing left was to try to get away from this herd somewhere.»

Kalinin quickly received an invitation from his colleagues to Rio de Janeiro. And then he soon received an invitation to China. China was chosen because there was three times more money than the Brazilians, the university provided a large apartment, and the contract itself was potentially open-ended. Together with Kalinin, another colleague from his faculty went to the same university.

It took Kalinin and his family two agonizing months to reach the university in Guangdong province, which is the Chinese branch of Israel’s famous Technion University. It was difficult to obtain a Chinese visa in St. Petersburg — it was impossible to sign up to apply, due to the large number of applicants. When mobilization came, he decided not to wait for a Chinese visa here and flew to Israel.

«I wrote to the Technion in Haifa that I could either run to Uzbekistan or go to them, since they were my employers. They replied: come to us for now, you’ll get your visa here. In Israel they gave us a visa in three days, but we were able to apply for it only when the October holidays were over. So we lived in Haifa for over a month, moving from apartment to apartment, and then we had a quarantine in Shanghai, when you count the minutes to get out. Travelling for almost two months with an intermittently sick young child is not easy.»

Kalinin has long since resigned from the HSE and from St. Petersburg State University, but continues to teach a special course for students remotely. Although he understands that this will not last long, because online teaching does not achieve the necessary effect, unlike face-to-face communication. Whether the system of mathematical education and the selection of strong students will be able to survive in Russia at all, he does not understand.

«Russia is on the edge of a precipice. And this whole system of additional education, circles, Olympiads, can be washed away in six months. For example, if inflation hits 200%, all young mathematics teachers will leave to work as programmers. Life in general has lost its predictive power. I don’t understand what will happen to Russia, and I don’t understand what will happen to China. I have found myself in a country that may itself start a war against Taiwan tomorrow. In this case, as we were reassured, the Israel Defense Forces will come for us as employees of an Israeli university.»

The hope for the IDF is not in vain. In 2022, Israel accepted more runaway Russian mathematicians than any other country. Today almost every major university in Israel, such as the Technion, the University of Jerusalem, Tel Aviv University, the Weizmann Institute, and Haifa University, has had mathematicians from Russia.

Suitcase, Terminal, Uzbekistan, Israel

Victor Vasiliev, an academician of the Russian Academy of Sciences, the chief researcher at the Steklov Institute of Mathematical Sciences, one of the first to sign the anti-war letter of scientists, fled to Uzbekistan soon after mobilization began, together with his sons of conscription age. Conditions were close to a night shelter. Upon learning of this, Sergey Yakovenko wrote to him about a special programme for scientists from Russia and Ukraine at the Weizmann Institute in Rehovot. It was an opportunity to get away quickly and think about what to do next.

«Sergey, in his own words, works full-time as Grandpa Mazai, who urgently rescues several dozen hares in distress. When I arrived in Israel, I immediately found several key staff members of the HSE math faculty next to me. It is difficult to say exactly how many staff members have left HSE, because everyone is trying to make sure that the educational process remains intact. And not so many employees have left from Moscow’s Steklov Institute, although only a few of them openly support the aggression in Ukraine. Most, as I understand it, hope to sit it out and live until better times.»

In the early days of the war, the Weizmann Institute responded to the call of international scientific organizations to accept refugee scientists from Ukraine. However, there were few of them, because the exit of men from the defending country was closed. Then Sergei Yakovenko, a professor in the Weizmann Institute’s Faculty of Mathematics and Computer Science, along with his colleagues convinced the Institute’s administration to give access to this program not only for Ukrainian colleagues, but also for Russian ones:

«Unlike European airlines, El-Al did not cancel flights to Russia, but, on the contrary, increased their number and set up an air bridge. And my colleagues and I pressed the administration and the President of our institute to start to help refugees from the Russian-Ukrainian war without specifying sides or nationalities. They decided to accept everyone.»

The program covered an academic visit of up to three months to the Weizmann Institute. The Institute provided free lodging, paid for the flight to Israel, and gave $100 a day for food. Decisions were made within 24 hours. All that was required was a proof of academic status.

«We had no accounting or bureaucracy, no votes, no committee meetings, no CV studies. There was no reporting required in the final. We had two goals — to get to know people and to give them a temporary break. We assumed that some would be able to find a position in other countries within three months, some would decide to repatriate and use the time given to find a suitable job at one of the Israeli universities or colleges, and some would be so great that we would want to take them to the institute for good.»

And all three of these trajectories worked. In the first wave, about 50 scientists and their families arrived between March and the end of the summer. Some of them had already gone to the U.S., and some had found jobs at universities and colleges in Israel. And the program was about to be closed, but in September, with the announcement of the mobilization, the second wave broke out.

«And here the main problem was not to find new money, but to stop our intra-university “bulldozer.” The fact is that we were settling refugees in the institute’s old service housing, which according to the long-agreed reconstruction plan should have been demolished in December. And then 50 new people arrived with their families. Where would we put them? And here I had to warm the telephone receiver with my cheek.»

Then the Weizmann Institute decided to extend the program for refugee scholars until March 31, 2023. Israel’s academic system for Russian scholars, both young and old, was much more flexible than in other countries. Students who did not have a bachelor’s degree had begun to be accepted into Master’s programs, giving them the opportunity to take the exams they lack before completing their degree in Israel or at their home universities «remotely.»

Researchers over the age of 60 were offered at least temporary jobs for a few years, even though in the old days they wouldn’t have had a chance. The most difficult thing was to find a solution for mature mathematicians, already crowned with world fame, but approaching the retirement age of 65. In Israel at this age, professors are obliged to retire, passing into an emeritus state and making vacancies for the young. This is a huge problem (labor and pension laws are the same for everyone), but various universities have begun to look for creative ways to solve it in individual cases. An understanding of the exceptionality of the moment and the need to find unorthodox solutions has emerged.

«I long ago stopped dividing mathematics into Russian, Israeli, European, American, — Yakovenko says. — Good mathematicians are like an endangered species of some rare whales, and if a new whale is born somewhere, we carefully pass it from flock to flock so that it becomes part of the whole species, not part of an individual flock. Conversely, if an old whale finds itself in difficult conditions, the others just instinctively gather and nudge it with their noses to keep it afloat.»

Similar programs have started up at other Israeli universities. Thus, dozens of mathematicians from Skoltech, Moscow State University, HSE, and POMI have temporarily landed in Israel.

«Goal-setting is lost»

Boris Feigin received a position for a year at the University of Jerusalem, but did not withdraw affiliation of HSE.

«Now the HSE is in a waiting position, but it is not clear what exactly it waits for. It has become impossible to work in the former mode, because the goal-setting has been lost. Previously there was an orientation to the global scientific world, the global educational market, now it is either impossible or even prohibited. Moreover, there are instructions from the Ministry of Science to establish an upbringing process among students. But the administration of the HSE understands that it will not be possible to preserve the structure of the university in this case, and so they are not doing anything about it.»

According to Feygin’s estimates, about 20% of lecturers have left the faculty of the Moscow State University, but many more are leaving. True, most of them are trying to keep at least an informal connection with the faculty. No one wants to leave scorched earth, and there is a desire to put the process on pause. Many are willing to return should the political situation normalize, though they understand that it will take years to rebuild the math structure that was destroyed in 2022.

«The horror is that there will be nowhere to go back to. We will have to build everything from scratch, and no one knows how long that will take. And this despite the fact that our math department is not yet the most damaged by the war. That’s who suffered a truly irreparable loss, as they used to say in Soviet times, was the Faculty of Computer Science, which was built in interaction with large companies such as Yandex, Huawei, and Samsung.»

«For myself internally, — Feigin says, — I haven’t solved the question of a connection with the HSE. And I haven’t solved the issue of coming back either.»

Until October, Anton Khoroshkin was the deputy dean for academic work at the HSE math faculty. Now he works at the University of Haifa. He made the decision to leave in spring, but didn’t leave the HSE until he was sure that the educational process would be set up in the fall. The department has a hundred faculty members and five hundred students. He knows exactly who left where, but he won’t talk about it, and he still says «we» about the faculty.

«The losses are substantial. Imagine if you have three-quarters of your algebraists leaving, it’s a serious blow to the educational process. We’re still trying to save seats for some staff, and I’m not prepared to disclose details. Some have left to wait it out, and some have left for good, slamming the door. In March, those who were visited at home by the enforcers, left. But they continued to teach their classes remotely for the rest of the year. Another part of the staff left in September after mobilization, and they, too, continue to read remotely. Ten percent of the students left. We helped all of the undergrads who asked to grad schools, but the first and second year students had the hardest time leaving.»

Khoroshkin was one of the few who got a permanent position in Israel. But most live in anticipation of visas to Britain and the United States, where the university labor market is much wider.

In addition to the HSE, there are still active mathematical centers in Moscow: the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics at Moscow State University, the Steklov Institute (MIAN), Skoltech, and the Kharkevich Institute for Information Transmission Problems of the RAS. They do not form a single ecosystem, as in St. Petersburg, but each of them is on a different stages of the process of severing international ties and flushing people out. Some of the mathematicians had managed to leave Skoltech and IITP before the two institutes fell under U.S. sanctions. Only a few left Steklov Institute and MSU at first, until the September mobilization gave it new impetus.

«In the first week of the war I wrote to my friends in Moscow in Steklov Institute that I was ready to look for some positions for them, but most refused, — says Andrei S. (name changed), a professor at one of Britain’s universities. — And in the fall, because of the mobilization, people began to actively think about leaving. “In the first week of the war I wrote to my friends in Moscow in Steklovka that I was ready to look for some positions for them, but most refused,” says Andrei S. (name changed), a professor at one of Britain’s universities. — And in the fall, because of the mobilization, people began to actively think about leaving. Although almost everyone over forty understands that they will not find a normal job in the West, and it is very hard to survive on temporary positions. Now it is very difficult to fit into the Western scientific system. Thousands of people are looking for а work, the competition is enormous. The times of the 1990s, when our scientists were willingly hired everywhere, are gone. There are no prospects. Many people understand this and are in no hurry to leave Russia, where they have a guaranteed job until their old age. But we preserve scientific communication and try to write articles together. True, I am afraid to go to Moscow because of the mobilization, so we decided to meet on neutral territory in Turkey. Turkish universities are happy to host us. They have no money for inviting foreign mathematicians, but the Moscovites do not need money, they have money, because all the money allocated for foreign trips remained unspent.»

Before the war, Andrei himself was also a freelancer at the International Laboratory of Mirror Symmetry and Automorphic Forms of the HSE. He withdrew his affiliation with the HSE in the first week of the war.

«In the first days there was the strongest shock: Russia is bombing a neighboring country! I realized right away that I didn’t want to be involved in that. And I didn’t want any problems in Britain. The HSE was, in a sense, the flagship of public education in Russia, a calling card. It was a successful rich university, closely connected to the government, and I realized that I no longer want to be associated with it. For example, in April, my own grant in Britain was frozen because a colleague from the HSE Faculty of Mathematics was scheduled to visit it. I had to remove him from the grant and replace him with a mathematician from Japan, and then the grant was reopened.»

In Britain, most of the grants for physics, mathematics, and chemistry come from the national Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC). In the first month of the war, the council issued a directive that these grants could not be spent on scientists with Russian affiliation.

Britain has two major mathematical centers, the Isaac Newton Institute in Cambridge and the ICMS in Edinburgh. They were harshly told that now you can not only invite Russian colleagues to short seminars, but even let them to make a talk on the Zoom. But they could take them out. In Britain, a fund has been organized to help mathematicians from Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus. In the future, this program is expected to support any scientists fleeing the wars, regardless of the countries where the wars take place.

Alexander Shapiro, a researcher at the University of Edinburgh, became the coordinator of the program:

«In February, I stood outside the Russian embassy for four days in shock. Then I heard from the head of our department that the Newton Institute had opened a program called Solidarity for Mathematicians. The program is designed so that Newton Institute gives a candidate a small amount of money for a year, who in turn must find an institute in Britain, where he could be accepted. But to go to the institute, you have to get a visa, and this is a very complicated process, which the universities in Britain cannot influence.»

So far only one scientist from Ukraine and two from Russia have come under this program. Most Russian scientists cannot get to British universities because of visa problems. A similar situation developed in the United States, where, unlike in Europe, there are many universities, and therefore many places to work. However, only a few have managed to get there. The reason is the same — the U.S. gives almost no work visas to scientists from Russia. Despite President Biden’s statement that it is necessary to make it easier for Russian scientists to enter the country, this did not happen in practice.

The outcome of the war year is this. There are money for mathematics within Russia. Student losses are less than scientific and teaching losses. International contacts remain at the level of human connections. Participation in international conferences is almost impossible or technically difficult. Participation in Western grant programs is forbidden. And there are three unanswered questions: will the system for the selection and training of talented students persist, who will teach these selected students, and how will mathematics develop in Russia under conditions of international isolation?

While no one has an answer to the first two questions, there are some theories about the last one. Victor Vasilyev, a Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences and chief researcher at the Steklov Mathematical Institute, believes that mathematics in Russia is now at a bifurcation point:

«Imagine that the cavemen have a storm drowning a fire, but the embers in it are still warm. And now we’re sitting here watching: could they make a fire out of it, or is there no chance? That’s the question I ask myself, and I can’t find an answer.»

His colleague at the Steklov Institute, Corresponding Member of the RAS and Professor of the Faculty of Mechanics and Mathematics at MSU Ilya Shkredov thinks that in mathematics, which does not depend on equipment supplies, you can always sit and think about something useful, but the general trend will be directed toward marginalization and localization.

«My guess is that the young fields of mathematics will survive in the near future: the embryonic and relatively young sciences created during the Soviet period. How long will they last? I think we should not guess here either, but just look at how soon a provincial school left by its founder usually dies (there are many such examples in Russia), the timing will be comparable.»

And Andrey Okunkov assessed the probability that Russian mathematics, while in complete isolation, will remain at a sufficiently high level, with the probability of coming out of the black hole alive and unscathed.

In the process of preparing this article, half of the persons interviewed, even those already working under contracts abroad, chose not to give their names, as they continue to teach students remaining in Russia unofficially. Many hope that the political situation at home will change after the war is over, and so allow the possibility of returning home. Mathematics in recent decades has been was shining in Russian science too bright to forget its light so easily and quickly.

Text: OLGA ORLOVA

Letter of Russian Mathematicians Against the War

Mathematics has always been one of the few areas of fundamental science in which Russia has maintained a leading world position. As proof of this, Russia was to host in the summer of 2022 the most prestigious mathematical conference in the world, the International Congress of Mathematicians. The International Mathematical Union cancelled this decision due to Russia’s attack on Ukraine. In a situation where our country has become a military aggressor and, as a consequence, a rogue country, Russia’s leadership position in world mathematics will be irretrievably lost.

Olga Orlova 24.02.2023